“We have a whole people immersed in these beliefs... It is the basic concept of our civilisation. Governments will come, governments will go, but [the family unit] endures.” – “A conversation with Lee Kuan Yew,” Foreign Affairs, 1994

Since independence in 1965, the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) has often emphasised Singapore’s vulnerability to a myriad of potential economic, political and cultural crises, ranging from a Communist takeover and violent racial conflict, to an invasion of dangerous decadence and individualism from the West.

There is a current of anxiety that runs through our national identity, a frantic urgency to find a tie which binds our young, multi-racial, multi-religious country, so that we can be united against these potential catastrophes on our doorstep.

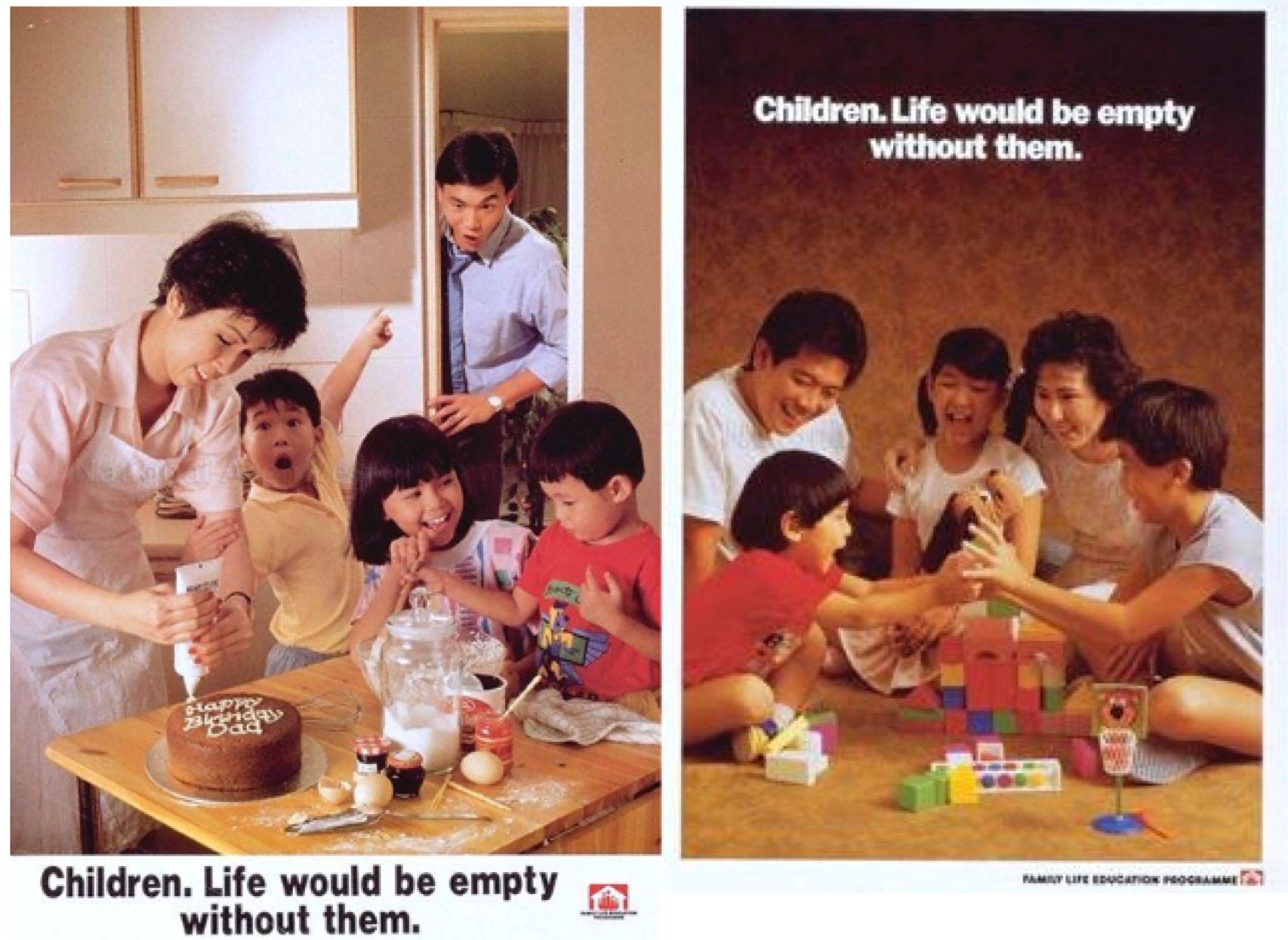

Within this narrative of crisis, the traditional family unit—father, mother, children—has been positioned not only as the bedrock of society, but as one of our strongest defences. Abiding by the nuclear familial structure would apparently give our vulnerable country a robust workforce, a stable socio-political foundation, and strong cultural roots in our Asian heritage.

The preservation of the traditional family unit has thus always been framed as fundamental to Singapore’s survival. Over time the drive to defend and protect the traditional family unit has evolved into a deeply rooted, almost primal instinct—the nuclear family is not only vital to our nation’s future, it is essential for individual happiness and success.

We’ve come to view the organisation of society exclusively through the lens of the traditional family unit. Hence, it’s imperative to ask: how has this lens coloured all of our perspectives, not just those who do not conform to the traditional familial structure? How have we become blind to a more expansive vision of Singaporean society, of our families and of ourselves?

First, it’s important to grasp the depth of this faith in the family, best captured in that 1994 interview of Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s first prime minister, by Foreign Affairs. For Lee, the nuclear family transcends the limitations of both time and space, its strength outweighing even the longevity of the PAP. The traditional family unit takes on a universal, almost religious quality in his mention of a Confucian value, “修身齐家治国平天下”, which is loosely translated as “cultivate yourself, look after the family, govern the country, all is peaceful under heaven.”

These nine characters encompass the ideal Confucian social structure. The dynamics of the traditional family unit are mirrored in all other aspects of society—everyone has their role and must perform it if we are to achieve peace and harmony. Fundamentally, there is a symbiotic relationship between the traditional family unit and society.

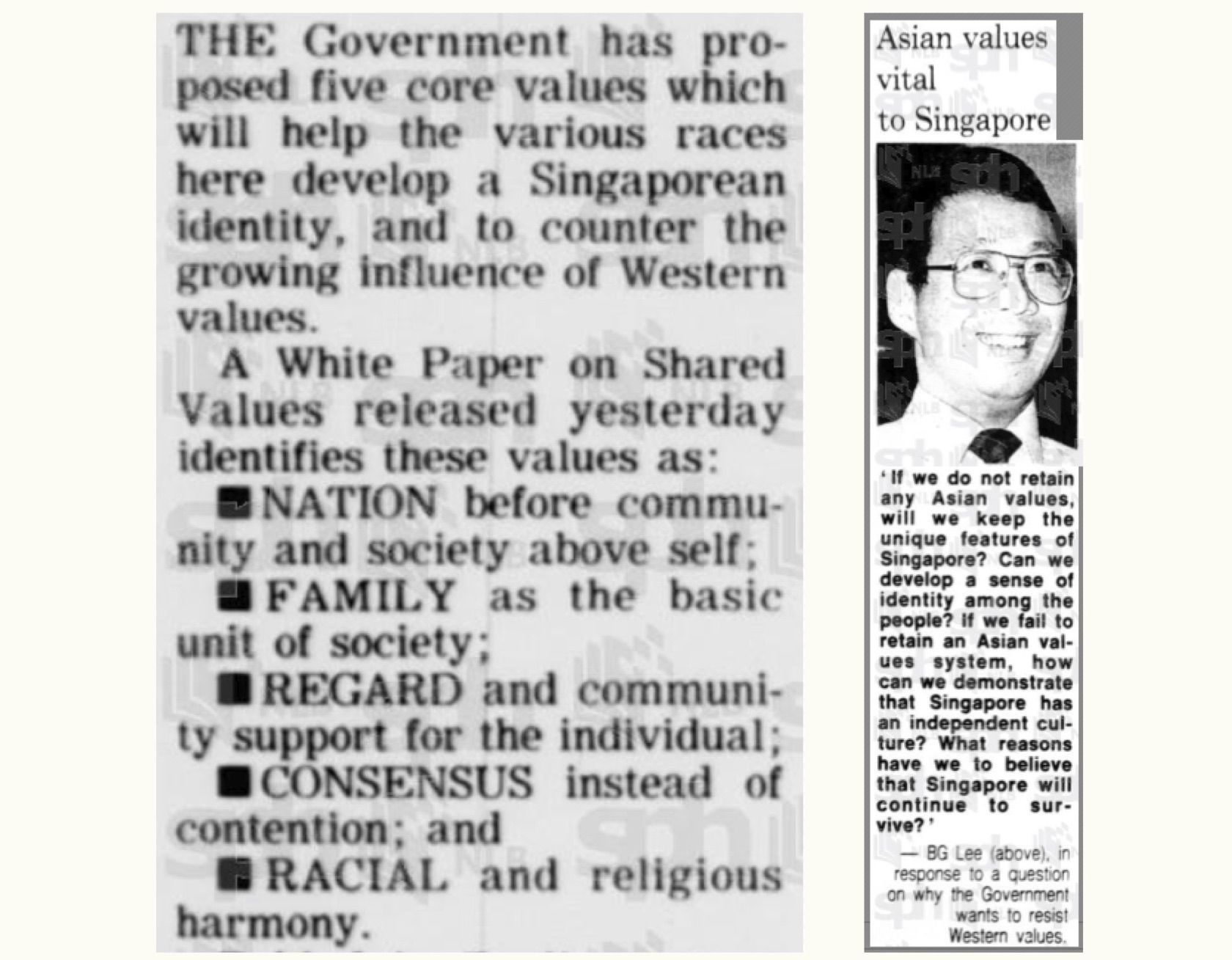

Lee also said that “we have a whole people immersed in these beliefs.” It is this same line of reasoning that shapes the PAP’s paternalism. Drawing parallels between its leaders and Confucian gentlemen (君子), the PAP called itself a “government of honourable men [who] have a duty to do right for the people and [gain] the trust and respect of the population.” By relying on (and warping) traditional Confucian thought—often under the guise of neutral terms like ‘Asian values’ or ‘shared values’— the ruling party not only justifies but normalises its paternalistic grip on Singaporeans.

When the birth control pill became wildly popular and widely available in the 1980s, Lee believed that it would hasten a decline in the West. According to Lee, oral contraceptives were to blame for promiscuity, leading to the “total breakdown of all family control over children, and a new kind of society where you shack up with people and have one-parent families.” Lee’s moral disapproval of a woman’s decision to use birth control directly echoes the Confucian relationship between family and society: one individual’s supposed immorality could lead to the erosion of the traditional familial structure and, eventually, the decline of an entire nation.

This protective instinct has manifested itself across society: our housing policies enshrine the married couple in law, while excluding singles and non-heterosexual couples from access to public housing; our education system focuses on preserving “the family as the cornerstone of our social fabric” by “encouraging healthy, heterosexual marriages and stable nuclear family units”; and now, most recently, the desire by today’s PAP, led by Lee’s son, to amend the Constitution in order to “protect Parliament’s right to define marriage”.

These are only the most obvious examples of how the traditional family unit has become the focus of a network of interlocking institutions of power. The desperation to produce more units of the nuclear family bleeds into less obvious policies as well, including the relatively high cost of birth control and STI testing, and the rigidity of adoption laws.

Moreover, in a capitalist economy run with a 'growth-at-all-costs’ mentality, the traditional family unit is fetishised and exploited for its ability to supply the machine with labour, a crucial factor of production. In the cold calculus of economic growth, the individual is a cog in the machine; and the traditional family unit is the supplier of that cog.

This utilitarian view of citizens is evident in the haphazard nature of the PAP’s population planning policies of the past half century. In the 1970s, Singaporean families were told to “Stop at Two”. By the 1980s, when it became apparent that insufficient cogs were being produced, women were incentivised to have three or more. Some might argue that all governments implement anti-natal and pro-natal policies.

But not every government infuses eugenics into its natal policies. The Graduate Mother Scheme of 1984, aimed at boosting the birth rates of university-educated women, was primarily motivated by the anxiety that less-educated women, many from ethnic minority groups, were reproducing at higher rates. From the 1990s, when it became obvious that natural population growth couldn’t keep up with the PAP’s economic fantasies, high immigration was proffered as the only answer (as opposed to, say, greater welfare and maternity support for low-income or single parents).

Therefore, the reproduction of nuclear family units has always been the primary, most intense purpose of the government and its multiple arms of power. And it is this purpose to which Singaporean sexuality has always been anchored.

In its commitment to the traditional family unit, the relationship between Singaporean sexuality and state power is often characterised as repressive. But the relationship is not as simplistic as that between oppressor and oppressed. As French philosopher Michel Foucault theorised in The History of Sexuality, the power of the family unit circulates within the population, making us complicit in mutual surveillance and control.

In other words, repression is equally productive. Productive of a national discourse surrounding sex that is limited to birth rates or sex crimes and nothing in between. Productive of a financial and social pressure to marry for the freedom of owning a home. Productive of the social shame imposed on single women or married couples who choose not to have children. Productive of an incentive to stay in a marriage, at the expense of one’s own happiness or even safety, because of the legal and economic repercussions. Productive of the enforcement of strict gender roles, regardless of how limiting it may be for both men and women.

As a result, the sexual Other (the non-cisgendered, the non-heterosexual, the non-married, the non-parent) is not only different from the married heterosexual with children. They threaten the very economic, moral and cultural foundation of Singapore. Hence, a deviation from the nuclear family incites not only discomfort, but existential fear and ontological anxiety.

How much of this fear is unfounded and to what extent is it justified? Discussions about the possibility of loosening the tie between national survival and the traditional family unit are thwarted time and time again by the East versus West binary.

By framing liberal America and European countries as the source of decadent, individualist and deviant sexuality, we reinforce a strict binary between Eastern conservatism and Western liberalism. It becomes easier to amputate ideas and persons that jeopardise the traditional family unit because it supposedly exists outside of our Asian heritage and culture.

“Homosexual rights are a Western issue,” Wong Kan Seng, then minister of foreign affairs, told the 1993 United Nations World Human Rights Conference.

Now, almost 30 years later, we continue to construct, enforce and perpetuate narratives about imported moral deviancy from outside of Singapore. The most fashionable narrative now is the pointing of fingers towards the “woke Left”, a supposed group of keyboard warriors who have been brainwashed by half-baked social justice ideals on Instagram infographics and minute-long TikTok videos posted by Western influencers. By holding on to this binary between East and West, we effectively create a common enemy, a tangible source of pollution that can be used as a scapegoat for the sexual Other.

But with this scapegoat in place, we are robbed of the chance to have a frank, productive discussion about the real consequences of protecting the traditional family unit and no one else. We are deprived of the opportunity to create space within our own Asian heritage and culture to accommodate an evolution in the understanding of family and of love, to expand our idea of parenting to a more communal, less isolated one.

We must stare unflinchingly at the cost of preserving the traditional family unit in its current position of exclusive power and ask ourselves, are we willing to bear it? If not, how can we, as Singaporeans, move towards being more imaginative about how we organise society?

Jean Hew is Jom's head of research. This essay is one of several that Jom is publishing free to coincide with Singapore’s 57th National Day.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.