‘But you seem normal.’ That’s what people would say when I tell them that I am hard-of-hearing. In response, I would say thanks and congratulate myself for yet another successful deception.

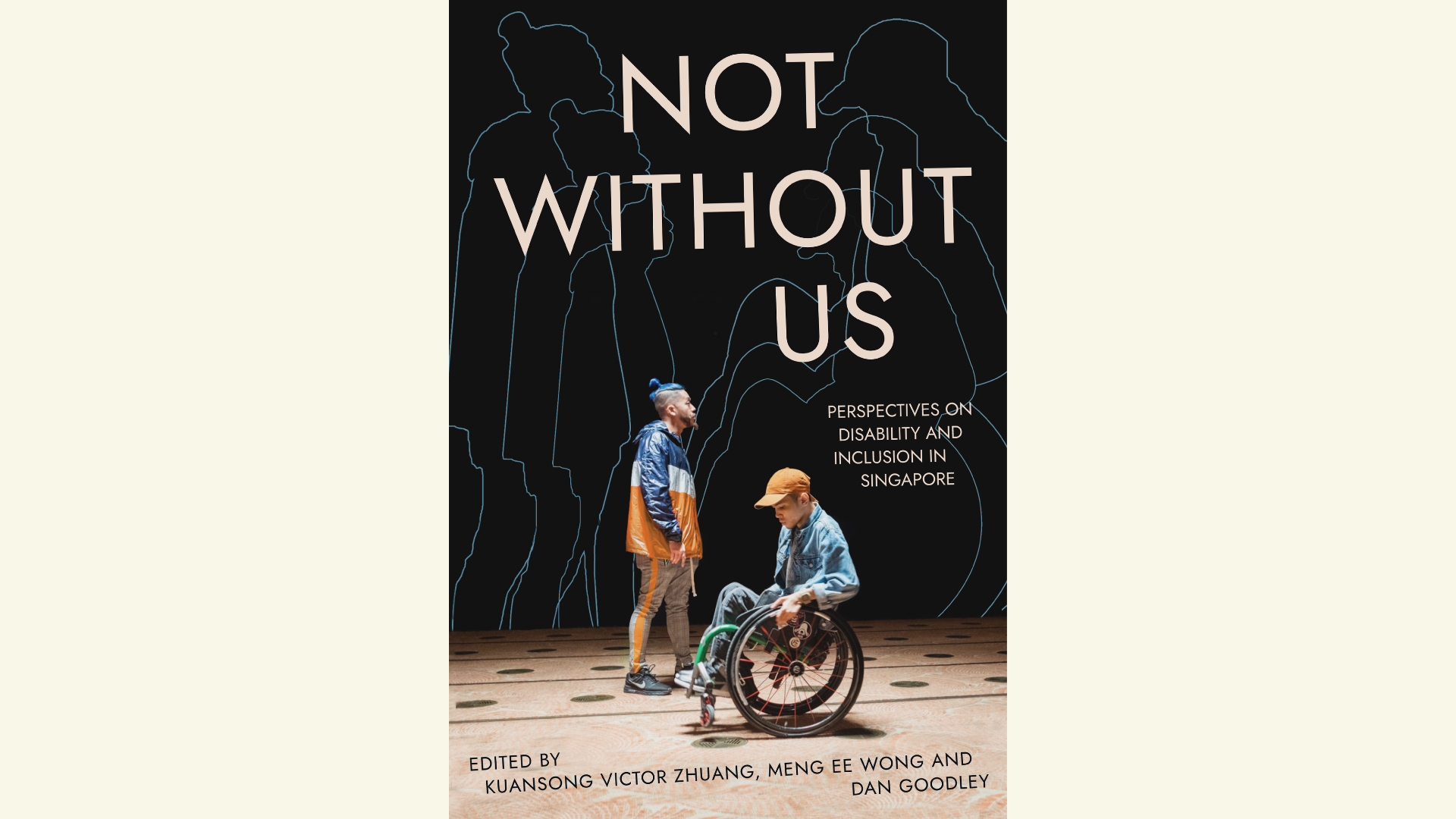

- From “You Are Not Hard-Of-Hearing Enough: Performing Normativities” by Xie Yihui from Not Without Us: Perspectives on Disability and Inclusion in Singapore (Ethos Books, 2023).

Disabled inspirations

What was it like to be a disabled child?

I loathed my disability because it makes me different.

I was ridiculed for being slow in games.

I watched uncaptioned animations, lost, but laughed along with other children.

I dreamt of being normal.

But I found solace in what would now be called the inspiration porn, where disabled people’s lived experience is objectified for the benefit or enjoyment of the non-disabled. On my family’s ceiling height wooden bookshelf, there was Hellen Keller’s Story of My Life, on her being deaf-blind before 1 year old and going on to become a prominent writer, scholar and political activist. I was captivated by the story—it reframes failures and hardships as essential components and, in fact, precursors of glories. And that became the then-narrative of my life.

To my younger self, disabled heroes differ from non-disabled people only by virtue of the challenges they experience. And they always overcome those challenges and become exceptional, never failing. Disability is merely material and the exterior, like many other challenges in life.

What resulted from this perspective was a mindset that I must overcome my disability to be normal, that I can become exceptional. As there is no intrinsic value in disability except as adversity, I need to cast it away. Overcome it. Overcoming means running the extra miles, sucking up humiliation and shame, and sometimes, pretending that I am hearing. Ironically, it is when I strove to overcome a disability that disability ended up taking up much of my mental space. I internalised the ‘problem’ and looked inwards, trying to fix my disability. Overcoming became overwhelming.

The dominance of ‘inspirational porn’ narratives, according to Mitchell and Snyder, emerged against a neoliberal backdrop where human worth is measured by its relative utility within the capitalist machine. Only when a disabled person proves themselves to be productive can they gain admission to the consumerist society—a phenomenon termed “ablenationalism”.

Against this, Mitchell and Snyder argue that the inclusion of disabled people becomes meaningful only if disability is seen as providing another mode of living, contrary to the predominant norms of independence and productivity. Disability itself is productive of new knowledge and consciousness.

And I had my experience of ablenationalism in China’s exam-driven schooling system. When I was 12, I went to a middle school where most of the city’s top scorers go. I saw red boards showing individual rankings in the latest exams along the corridors on our way to classrooms, to toilets, to the performance hall, looming above the water dispensers where we took breaks from Mathematics, Chinese and English. The moment I entered that school, I knew I must work hard. I must fit in. I must prove my value by having my name appear as high up on the red board as possible.

At that time, I did not know about learning accommodations, nor did the idea of telling people about my disability cross my mind. Out of a sheer desire to fit in, I learnt how to ‘listen’ with my eyes, lip-reading, noticing context clues and expression changes. The more I mastered visual clues, the more often I felt ‘normal’. I learnt that I cannot clarify every single word that I cannot hear. I should nod confidently, offer generic responses or casually start a new topic so I can follow. In a group, I would sit in the central or center-right positions so I can hear from the left—my better ear. Every moment of functioning or pretending to function like a hearing person is a mini success, and once this becomes an “unbroken series of successful gestures” (here I tip my hat to Jay Gatsby), I pass as a hearing person.

Performing normativity

Around the time I discovered these inspirations, I started wearing hearing aids and as a result, experiencing a hearing person’s world. I started hearing things that I was never able to hear, I no longer shied away from talking to people. Instead of feeling totally left out in conversations, I began chipping in now and then.

But simultaneously I was haunted by an embedded fear, the fear that my hearing aid batteries may run out. It could happen at any day, any time, halfway through a conversation, a lecture or a movie. Then a signal sound for a low battery would start ringing—a siren that says: this is a gentle reminder that sound doesn’t belong to you and you are incomplete without properly functioning hearing aids. If I forgot my batteries—that almost never happens right now because ‘battery check’ has long been the conditioned reflex activated at the moment I stepped out of my door—the sound would get dimmer and gradually fizzle out. So would a part of me—the chatty, confident person that I claim to be myself.

I hide myself behind a calculated self-invention, a convincing character in my private aspiration but also to the external world. Do I own her, the one empowered by technology, unbridled by silence? Can I be sure that my identity remains unchanged after years of living with electronic organs?

These internal conflicts aside, I worked hard to pass. My labour translated to some mini successes and a few mishaps, but over time my ties with the hearing world took root. I pretty much succeeded in passing as non-disabled. Most friends and teachers from my middle school don’t know about my disability. After hearing about it, they would say, “No! You seem perfectly normal.” And I wondered, how can I not be proud of that?

In Judith Butler’s theory of performativity, she says that instead of being a gender, we continuously enact a gender. This illuminated the understanding of my experience. My repeated actions are culturally significant—it signals to myself and to observers that I am ‘normal’, whatever that means. Performative acts are building blocks of my hearing persona. Applying performativity to the act of passing, Cox Peta explains that disabled people seek a particular type of reaction from others by performing actions that give the perception of being non-disabled. Every performance of normativity is disability in disguise.

Passing is like staging a performance with impeccable sets, lighting and acting that make fiction reality. It still fools people; it fooled me too. I can’t find a single word about my disability in the diary I kept during middle school. I was consumed by the endless rat race for better rankings. I continued to do badly in English listening tests despite acing reading comprehension and writing. My English teacher blamed me for inattention. I blamed myself, too, for not working hard enough to cultivate an ear for the flow of English syllables. It never occurred to me that disability is out of my control; I thought that if I was able to create the make-believe, dignified hearing character, I could weed out hearing loss from my self-conception and eventually fix my disability.

There weren’t enough tests of my childish illusion before I scored the top three in the high school entrance exam and my name was plastered in the local newspaper. Those times were whirlwinds of praises, interviews and many opportunities that would change my life course, one of which was a four-year, bond-free scholarship in Singapore.

The excerpt from, “You Are Not Hard-Of-Hearing Enough: Performing Normativities” has been republished courtesy of Ethos Books, with permission from Xie Yihui. You can order the full book, Not Without Us: Perspectives on Disability and Inclusion in Singapore, here.

Xie Yihui has just graduated from Yale-NUS College, and is interning at Bloomberg as an economy and government reporter. She was previously the editor-in-chief of The Octant, her college's independent newspaper. When free, Yihui enjoys a good conversation over an oat milk latte or a Teh-C-kosong.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.