Jonathan Lim: The jester who held up a mirror

“Sibling fun at the beach,” Jonathan Lim posted a photo of himself on a breakwater with his two younger sisters, grinning widely against a gloomy horizon. “Feeling sunny despite the rain!” That was the theatre-maker’s final digital dispatch before his unexpected death, age 50, last week. The playwright, director and actor leaves behind an outsized body of work in Singaporean satire, where he frequently roasted local politics and current affairs over the open fire of his long-running “Chestnuts” revue—and transformed familiar fables like “Sleeping Beauty”, “Aladdin” and “A Christmas Carol” into deliciously high-camp and deliberately low-brow pantomimes, now a staple in Wild Rice’s annual theatre season. Lim was a one-man “Saturday Night Live”, often at his best in the short-form musical format or when he could put together a series of pithy vignettes, each devoted to pulling apart a specific subject. Here, he could set loose his zany, associative imagination within a strict narrative structure. He also deployed this gift in other settings; the gender equality non-profit AWARE regularly invited Lim to be part of its annual fundraising ball under the “Chestnuts” banner, where the team would skewer the most shocking incidents of sexism in the nation-state. In the 2020 edition, Cyndi Lauper’s feminist anthem “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” and Extreme’s saccharine ballad “More Than Words” are woven into a madcap musical medley about the gender pay gap in Singapore. “Girls just want the same funds!” the quartet belts, “More than words, it’s salaries that really make it real!”

Lim also relished the historical and the supernatural, and worked closely with The Theatre Practice to write its sprawling, ambitious promenade show, “Four Horse Road”. Audience members wandered through alleyways and buildings on Waterloo Street and encountered real-life stories from the area’s past, reimagined. “Jon was one of a kind: quirky, mischievous, imaginative, curious and a hell of a writer, who could not refuse a good creative challenge,” Kuo Jian Hong, the company’s artistic director, told The Straits Times. “He found humour in heavy subjects, and profundity in the ridiculous.” The two long-time collaborators were in the midst of conjuring up a new Chinese-language musical, “Partial Eclipse of the Heart”, set to premiere in August.

Kuo wasn’t the only one left to grieve in Lim’s abrupt wake. His death shocked peers and protégés alike, who took to posting long eulogies on social media, often accompanied by dozens of photographs of a beaming Lim, palpably kinetic in every frame. Friends and family told ST “there had been no outward sign of illness” before he was discovered, unconscious, in his flat by a close friend. The Singapore theatre scene has over the past few years been shaken by the untimely deaths of several thespians, including Timothy Nga, aged 49, Paul Ko, aged 23, and more recently, Shahid Nasheer, who was 28. Lim’s departure leaves yet another crater in a close-knit community, but also leaves behind a community of artists coming into their own, whose artistic sensibilities and directorial visions he helped nurture.

Jonathan Lim died on January 23rd. This obituary was first published in Jom on January 31st.

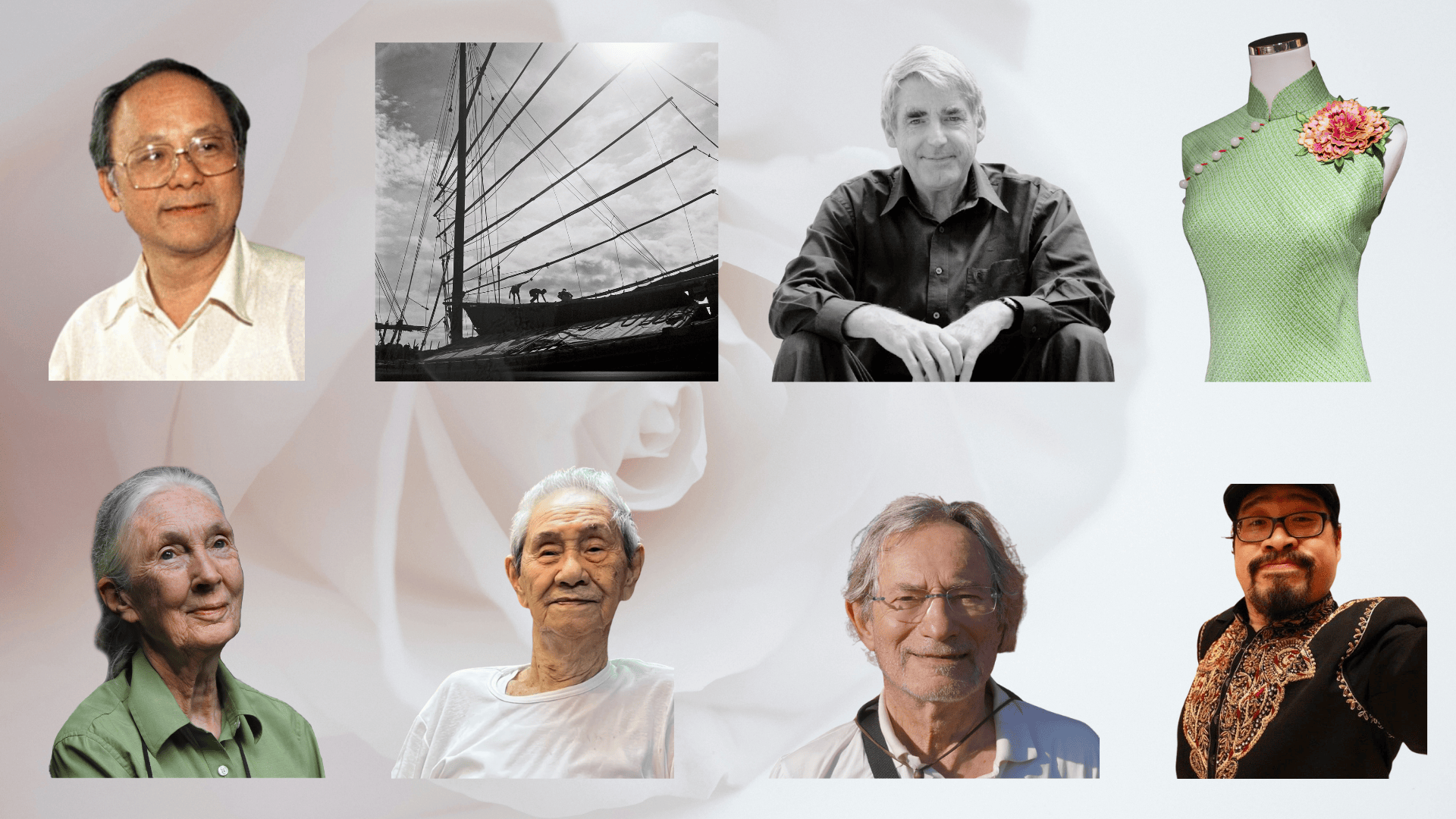

Lim Tze Peng: A restless artist, laid to rest

“There’s not a single day that I do not paint or write calligraphy,” Lim Tze Peng declared a few months ago, aged 103, ink stains on his pants and a huge smile on his face. “Art has given me longevity!” 20,000 artworks later, Lim has finally put down his brush. The Cultural Medallion winner, who was Singapore’s oldest living artist, died earlier this week following a hospital stay for pneumonia. Devoted to his craft and delighted by the world till the very end, the man who witnessed Singapore’s rapid urbanisation through his inks and oils had the rare thrill of witnessing his own legacy make history: his biography, Soul of Ink: Lim Tze Peng at 100, claimed the country’s richest book prize last year and, several months later, he had his first solo exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore. The retrospective runs till the end of next month and shows off over 50 of his works, which share the spotlight with scrapbooks and sketchbooks from his Telok Kurau studio and home. These previously unseen materials constitute his own meticulous “visual dictionary”, in the words of curator Jennifer Lam. Lim favoured thin strokes and delicate washes in his scenes of Singapore past—crammed with detail and painted en plein air—but also thick columns of hutuzi (糊涂字; “muddled writing”) laid on paper with a forceful hand. This was a hand that had scrubbed school toilets while a young teacher, and later principal, of Xin Min School, and also hoisted brushes as thick as an adult’s forearm well into his 90s. Lim wasn’t just a prolific producer of art, he was also a sojourner, painting both under the swelter of the equatorial sun in Indonesian farmland and in the wind-swept medieval villages of coastal France.

He does leave behind one person who kept him company on life’s varied terrain, well before his paintings went for S$200,000 at auction, and when galleries demanded that he paint with “more colours” to make a name for himself. His wife, Soh Siew Lay, raised their six children and a brood of pigs, ducks and chickens on their farm, assisted him on location while he was painting, and often chided her dreamy husband when he spent his solo income on art books and inks instead of the household. He’d always been in awe of her, and frequently acknowledged her sacrifices: “She always said, ‘Art is your first wife, I’m just your second wife’.” Their unspoken affection for each other took a different language: the straightening of a shirt collar, the tightly clasped hands and, later on, his determination to give her dignity when dementia took its toll. This eulogy for him, then, should also be a celebration of her.

Lim Tze Peng died on February 3rd. This obituary was first published in Jom on February 7th.

Laichan Goh: The sartorialist nonpareil

Laichan Goh, who slipped women into sexy silhouettes—and also stitched showstoppers for the Singapore stage—died last week, aged 62. For seven years, the self-taught master of the contemporary cheongsam had struggled privately with brain cancer; the 13th of 15 children died surrounded by dozens of loved ones at Assisi Hospice. His younger brother, Eddie, will be taking over his eponymous atelier. Fashionistas and theatremakers alike mourned his departure. Tjin Lee, the entrepreneur behind the former Singapore Fashion Week, chose Goh for the coveted closing show of its final edition in 2017, calling him “not only a great designer but a great soul”. Goh brought a different kind of sensuality to the iconic Chinese garment. His insistence on softness, both of material and mood, meant breaking the rules of previous generations of stiffer, starchier cheongsams. Less suit-of-armour, more made-to-suit-her. Petals cascade down bodices, gossamer capelets graze the shoulders, and vertebral columns of tiny buttons ripple as his models float down the runway. He studied the traditional way of making cheongsams from a Shanghai-trained shifu, then studied the lifestyle and anatomy of the modern woman: gone were the 24-inch Maggie Cheung waists and rigid postures, replaced by working women on the go who needed to drive in a cheongsam, wrangle kids and groceries, and hunch over a desktop. Goh chose to drape and cut his fabric on the bias—diagonally, instead of vertically—so it would stretch with the body and forgive the fluctuations of weight. “I love and respect the traditional cut, but it has to evolve to survive,” he told Her World. Still, he kept some traditional touches, including buttons that run from the collar to the hip. “I like this detail because I think women should sometimes slow down a little and take time to enjoy the ritual of getting dressed.”

If Goh’s craft was the cheongsam, his art was costuming for the stage. Costume designers are often on the frontlines when it comes to soothing performers’ body image anxieties. Goh was part of this backstage contingent of sartorial caregivers: how to make a performer look (and feel) good—even when their character doesn’t. Ivan Heng, founding artistic director of theatre company Wild Rice, recalled the designer’s stage debut: the Singapore premiere of “Emily of Emerald Hill” in 2000. This monodrama, starring a cross-dressing Heng as the titular character, quickly became the company’s calling card. Goh sheathed Heng in a striking black gown with a generous bustle, deploying the stiffer taffeta alongside the softer French lace for a Peranakan matriarch whose steely exterior masks a vulnerable interior. Heng wrote in his social media eulogy: “[Goh] always designed with deep empathy — thinking about who the characters were, the circumstances they were in, and how the clothes could speak for them.” He left this world as he did the stage: sent off by a quartet, surrounded by flowers.

Laichan Goh died on April 14th. This obituary was first published in Jom on April 25th.

Anthony Reid: The chronicler of our many lives

Anthony Reid (1939-2025), historian of South-east Asia, died on Sunday. His contributions went beyond “great men of prowess” or the hard facts of trade and revenue: widely favoured topics of his predecessors. Reid wrote about spices, of course, and European merchants, but also women and the enslaved, royal musicians and masked dramas. He considered the religious traditions of Islam, Buddhism and Christianity to be real forces of social transformation in the region. Reid’s classic, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680 asked what made “South-east Asia”—a geopolitical invention of world war two—a region at all. Taking a leaf from Fernand Braudel’s grand history of the Mediterranean, Age of Commerce considered South-east Asia an integrated area based on physical and human geography interacting with each other over a very long timespan (the longue-durée). Slow, deep time created South-east Asia’s rivers and seas, which in turn gave rise to particular human patterns of movement and interaction. Between the 15th and 17th centuries, this structure interacted with various global developments—expanding world trade, the spread of universal religions—to bring about an age of material abundance, cultural refinement, and political stability.

Reid had his critics. But the concept of a shared cultural world, without borders and national identities, remains timely. Among his institutional legacies is the Asia Research Institute (ARI) at NUS, of which he was the founding director. It has been a major space of support for countless scholars. Late in his academic career, the master tried his hand at fiction. Mataram, “a novel of love, faith and power in early Java”, told the story of an East India Company man who falls for his Javanese interpreter. As news spread of Reid’s passing, numerous tributes lauded both his rigour and friendship. Ahmad Humam Hamid, of Syiah Kuala University in Banda Aceh, Indonesia praised Reid as an impartial student of the past. On the once-great Aceh Sultanate, Reid painted no “pure paradise”, but “afforded equal curiosity to manuscript and Man, to moss-grown tombstones and decrepit old mosques, to singing in marketplaces and to dirty alleyways.” Annabel Gallop, head of the British Library’s South-east Asian collections, said he was “completely without any airs, and constantly probing.” For all our time-traveling, historians must inhabit our particular time, and one particular life. But it is far from lonely.

Anthony Reid died on June 8th. This obituary was first published in Jom on June 13th.

Lui Hock Seng: The lensman who bathed us in eternal light

Every morning, he’d cycle from his home in Geylang to his job at Fraser and Neave, the beverage manufacturer, along River Valley Road, where he was due by 8am. He could do it in an hour. But he knew he’d dawdle, especially by the Merdeka Bridge, that busy commuter artery between the placid coast and the pacier city centre. So he always started out at 6am, also to catch the best light coming through the clouds. Slung around his neck was his most precious possession: a S$300 Rolleiflex camera, a present from his brother, who’d dug deep into his pockets for a high-end German model. What might a mechanic-turned-storekeeper do with such a handsome gift? He was drawn to patterns and geometries: silhouettes of seamen working beneath sail battens, like ribs against a bright sun; a labourer in a slant of light, pressed up against the crosshatched scaffolding of a rising building; a woodworker hewing rough logs into long, diagonal slats of timber. He didn’t know it then, but he was remembering the Singapore that his generation built, and that ours was starting to forget. He’d pull the camera up to focus with his left eye. While repairing a car, a metal splinter had struck his right, damaging it forever. But one was good enough. So were weddings and funerals, where he honed his craft. The occasional prize money from photo competitions was creatively and financially rewarding. So he kept making pictures, drawn to the daily rhythms of kampung life in Potong Pasir, Bedok and Tanah Merah, still lush with trees and flush with fields large enough for hundreds to gather for an impromptu silat performance. In 2012, he found himself a job at Singapore Press Holdings. While journalists and photographers collected bylines and the latest digital cameras, he collected their trash. He didn’t mind being an office cleaner. It was steady work, and he had an elderly wife and a disabled son to support. Then his younger colleagues discovered his black-and-white masterpieces and, for the first time, the 79-year-old became the focus of another’s lens. A French engineer, awed by his dramatic freezeframe of Ellenborough Market, its fishmongers resplendent in celestial sunlight, begged him for a print. It was the first one he’d ever sold. He would sell plenty more, aged 81, when the film and photography centre Objectifs mounted his first solo exhibition: “Passing Time”. There it was, his name in shiny black capitals on the gallery’s white walls. They had him stand next to it; he clutched at his soft khaki cap, slightly unmoored by the attention. But his lifelong companion, his trusty camera, with its strap pressing gently into his shoulder and back, grounded him. People showed up in droves and applauded his artist talks where, flanked by curators and gallery staff, he clapped for them, too. He had seven years left to live. Cancer would come for him. But he was satisfied—no, happy, even. He told his youngest son, before he died last week, that his wish had come true.

Lui Hock Seng died on July 26th. This obituary was first published in Jom on August 1st.

Tang Liang Hong: The rager against the machine

In 1987, with global communism on its deathbed, the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) somehow unearthed a Marxist Conspiracy in our little red dot. Ten years later, and some 32 years after independence, it again proved its investigative brilliance, when it revealed in our midst an “anti-Christian, anti-English-educated, Chinese chauvinist”. Lawyer Tang Liang Hong, well-known by then, only earned that sobriquet after deciding to contest in the general election as part of a Workers’ Party (WP) team featuring JB Jeyaretnam. During the campaign, the PAP’s leaders labelled him a bigot; the mainstream media dutifully parroted the accusation; and the PAP won Cheng San GRC with over 54 percent of the vote. Tang had lodged police reports against 11 PAP leaders for those statements. After the election, he paid the price: they sued him for defamation (and later won). By then he’d fled the country, and would eventually settle in Australia, also spending time in Malaysia and Hong Kong, where he died last week.

Tang, as academic Cherian George wrote in The Airconditioned Nation in 2000, had studied Indian dance when young, and could read and speak Malay. “His quarrel was with the over-Westernisation of Singapore, and he seemed to believe that Malay and Indian cultures were equally deserving of protection as Chinese.” Tang’s two daughters married non-Chinese men, and at his wake last week, there was a Christian service where one daughter’s church group sang and prayed. Tang was, in short, a really poor “anti-Christian, anti-English-educated, Chinese chauvinist”.

The PAP’s real worry about him was probably the same existential electoral one it has had since the 1950s: being outflanked by politicians who could better appeal to working-class folk steeped in their mother tongues. Over the past week, numerous Singaporeans have lauded Tang’s contributions to society on Facebook. George called him “among the biggest victims of Singapore’s political system of the last 30 years” (and has made available online his chapter about Tang). Leon Perera, former WP MP, said history will remember Tang kindly. Tommy Koh, ambassador-at-large who taught Tang at NUS, detailed several interactions with him over the years. One commenter asked about the government’s portrayal of him in 1997. Koh responded: “character assassination was often resorted to by desperate politicians.”

Tang Liang Hong died on September 15th. This obituary was first published in Jom on October 10th.

Jane Goodall: The seer who in the forest found us

A white woman in her khaki safari shirt and shorts potters around the tropical Tanzanian rainforest, her blond hair pulled back and her freckles catching the sun. She lifts up her binoculars and stares; a smirk forms, then a smile. Soon we see the chimpanzees who’ve become her family, who’ve helped her explain the interconnectedness of primates through our behaviours. Having observed David Greybeard—names, not numbers, she insisted—using a grass stem to extract termites from a mound, she knew that humans weren’t the only ones to use tools, perhaps the most notable of her discoveries, which would later be called “one of the Western world’s great scientific achievements.”

Because all the primatologists then were men, Jane Goodall had to scale academia in reverse: fieldwork first, classroom second. In 1961, she became only the eighth doctoral student accepted by Cambridge without an undergraduate degree. National Geographic published her first masterpiece in 1963, with photographs taken by the man she’d later marry. It released “Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees” in 1965, the first of over 40 films she’d be in. So seared in our global imagination are those visuals that countless other female primatologists she inspired would be mistaken for her. Never again would a young female researcher have to worry about not being taken seriously in the forest.

After she’d shattered gender stereotypes through her instinctive grasp of mass media, she taught us how best to leverage celebrity. With a disarming, delicate demeanour, she relentlessly spread her gospel, making over 300 public appearances a year, right up to her death this week at 91. The Jane Goodall Institute, operating in over 25 countries, inspired millions of young people not only to understand the more-than-human world, but simply to believe in their own capacity for change. Its Singapore chapter opened in 2007, helping us live better alongside our long-tailed macaques, partly by reminding us that, whether on the edge of Bukit Timah or MacRitchie, we are the ones encroaching on their territory. Andie Ang, its current president, established herself through work on the critically endangered Raffles’ banded langur. Every time Ang speaks, she channels Goodall, and helps us ponder a 60-year spiritual journey from one equatorial country to another.

What else did Goodall teach? Doom and gloom awaken us to decimation, but “if you don’t have hope, why bother?” Evangelise gently, keep channels open, because “people have to change gradually”. Good zoos are good, partly because the wild, where other human threats exist, isn’t always a utopia for animals. And she called the forest “a temple, a cathedral of tree canopies and dancing light”; and there she felt close to a “great spiritual power”, existing in every living thing, which for lack of a better name she calls “God”, and from which she draws much strength. When Goodall was alone in nature, there were times “when for a moment you forget you’re human. Your humanness goes away, and you’re part of that natural world. It’s the most amazing and wonderful and beautiful feeling.”

Jane Goodall died on October 1st. This obituary was first published in Jom on October 3rd.

John Miksic: The time traveller who took us with him

At dusk on the fourth day of Singapore’s first archaeological dig, John Miksic trudged back to his hotel, shoes caked in rain-soaked soil; spirit heavy with disappointment. Of the five sites at Fort Canning, four had yielded little. “We did consider giving up excavating the fifth area…but later decided to try our luck,” he’d recall. As the team dug near the Keramat Iskandar Shah the next day, the earth changed colour, opening a portal to an undiscovered world. Beneath, 14th century Majapahit gold jewellery; beads made from Indian and Persian glass (Miksic would later confirm they were produced at a proto-factory on Fort Canning); and porcelain fragments from China’s Yuan Dynasty, prominent between 1271 and 1368.

Over the next five days, they unearthed more than 2,000 items that upended received wisdom and forever changed how we see ourselves. Singapore’s history, it turned out, stretched back not to the 19th century but the 14th. For long periods, it had been at the heart of a vast maritime trade network linking millions spread along a 10,000 km-long coastline—far from a deserted isle destined to remain so without British largesse and foresight. Miksic was convinced that tales of a flourishing medieval Singapore, recorded in the Sejarah Melayu and proved by his findings, inspired Stamford Raffles to choose it as a colonial trading hub.

Modern Singapore’s affluence “only seems surprising if one ignores the fact that Singapore has really been in the scene all along, displaying some signs of its future potential as early as the fourteenth century,” he wrote in Singapore and The Silk Road: 1300-1800, his 2013 magnum opus that spurred the Ministry of Education to change its secondary school history syllabus a year later, and won the inaugural Singapore History Prize in 2018.

The book was the culmination of three decades of work beginning from that 1984 Fort Canning dig, which the National Museum had invited Miksic to lead. He was then teaching at Yogyakarta’s Gadjah Mada University after stints in Kedah and Bengkulu. In 1987, he became a lecturer of archaeology at the National University of Singapore and later established its Southeast Asian Studies Programme—a national pioneer, and somewhat lonely for the fact. Public funding was a pipe dream, so Miksic relied on private grants from Royal Dutch Shell and the Ford Foundation among others. At times, his teams comprised students and citizen volunteers; at others, “museum staff, hired Indian labourers, and some national servicemen who were being punished.”

Time was tight too. Often, they’d conduct “rescue digs” days before development began on archaeologically promising sites. Still, astonishing treasures emerged, including Miksic’s favourite, “The Headless Horseman”, in style and material unlike anything else found in South-east Asia. Over his career, Miksic and his teams uncovered hundreds of thousands of artefacts: each a tiny affirmation of Singapore’s position at the centre of South-east Asian archipelagic life; each a small confirmation that even centuries ago, Malays and Chinese, and myriad other South and South-east Asians lived together on this bustling port-city. For the New Yorker who made these shores his home from 1987 until his death last week, this knowing of the self was vital. “Once you have enough to live on, you want something to live for: identity, a desire to know your ancestors,” he told the New York Times. “It’s an innate part of what it means to be human.”

John Miksic died on October 25th. This obituary was first published in Jom on October 31st.

Abhishek Mehrotra, Faris Joraimi, Corrie Tan, and Sudhir Vadaketh wrote these obituaries. Sakinah Safiee and Liyana Batrisyia contributed.

If you think it is important for all of us to collectively remember and celebrate people like Jonathan Lim, Lim Tze Peng, and others, do consider a paid subscription to Jom.

Letters in response to these can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.