This Zhao Lilin is a friend of mine

Always burnt out but I don’t know why

She still hasn’t learnt to draw the line

—The lines are blur!

You then blur!

I’m sitting across a conference table from a sniffling student. A curtain of hair is obscuring half her tear-streaked face, like some kind of makeshift bulwark between her body and the rest of the world. She hasn’t shown up for half the semester. I text her every week. Sometimes she responds; most times, she doesn’t. Her grades are so poor she runs a real risk of having to repeat the year, or take a leave of absence from school. I’m trying to convince her to submit a final essay, but can’t decide how firm or how gentle I need to be in the few minutes I have with her. The light above us is bright and sterile, and I can almost hear the fluorescent filament buzzing in my ears.

Then there’s the time one of my pandemic-era students tells me, over Zoom, that she’s beginning to explore sex work. Another student is so depressed she tells me she’s been catatonic for days. All my classmates seem to know what they’re doing. They’re on this path, she says, rubbing her palms frustratedly, but I don’t know what mine is. Another one says he missed class the week before because he’s just been discharged from the hospital after a suicide attempt.

In every one of these situations, I found myself fumbling for an emotional toolkit I was never sure I could assemble in time. I’d rehearsed for these moments. I was buttressed by courses in mental health first aid, the basics of counselling, being a first responder to survivors of sexual assault. I told myself: there must be some kind of effective emotional lifeline I’m offering to them that keeps my students afloat. I realised, only much later, that the life jacket I threw them was my own.

The kids have grown so tall

Yet I’ve not grown at all

Most days I can’t recall

All my mistakes

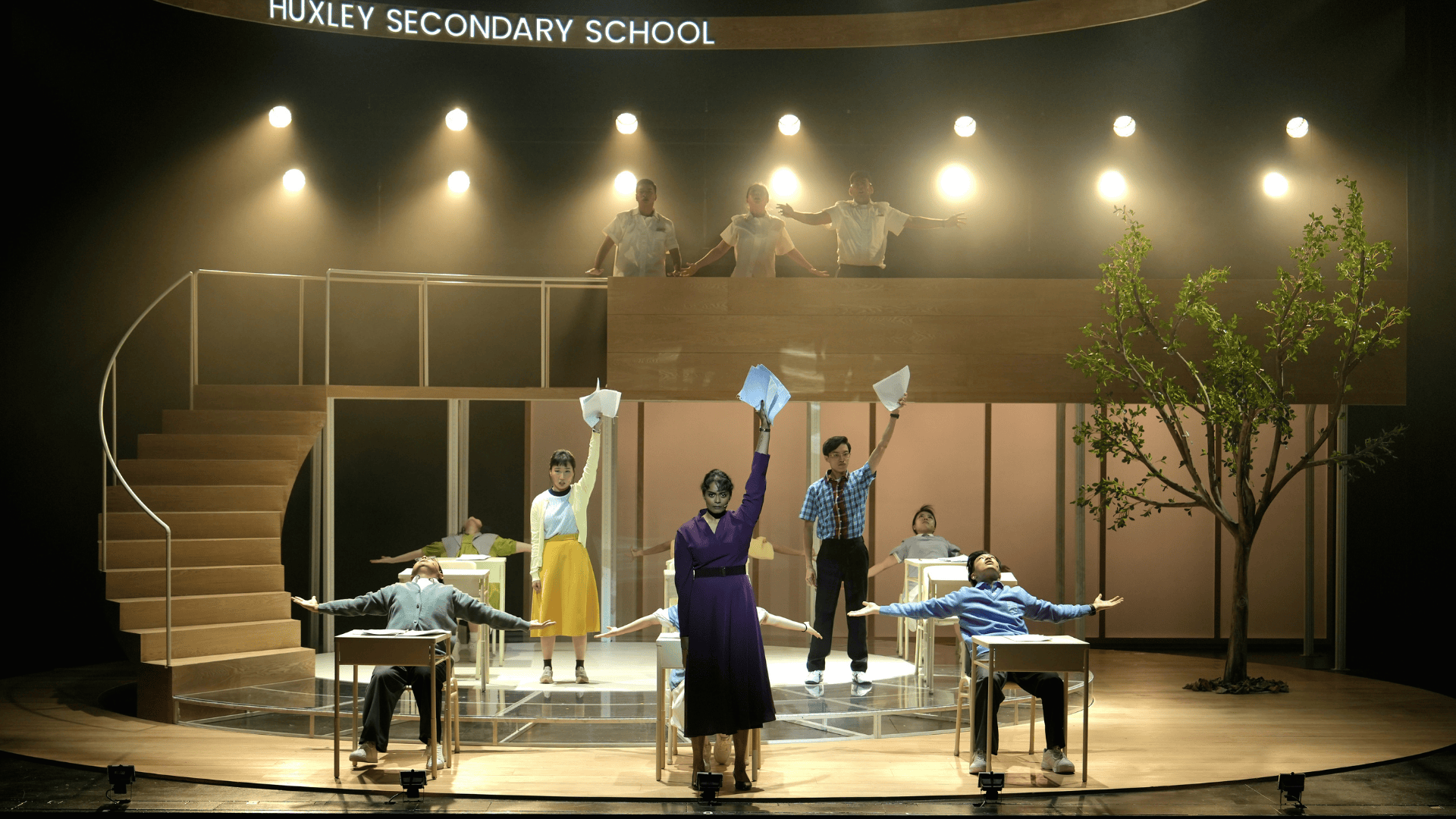

Lilin is in burnout territory and bureaucratic purgatory. “Aiya,” the secondary school literature teacher sighs as she embarks on her morning commute. “Aiya.” As Singaporeans we recognise how these two syllables can be supercharged with every shade of emotion from resignation and regret—to ferocious frustration. In weish’s hands, “aiya” becomes the musical building block and narrative bookend for “Secondary: The Musical”, the composer-musician-artist’s astonishing magnum opus that critiques the soul-crushing factory line of Singapore’s education system while also celebrating those attempting to keep the small fires of their spirits alive.

We follow the journeys of a trio of students alongside their teachers at various checkpoints in their careers. Our merry band of teen troublemakers and unlikely best friends are—what are the odds—a Chinese-Malay-Indian clique: Reyansh (Krish Natarajan), the timid intellectual who self-soothes by making measure of the world around him; Omar (the late Shahid Nasheer), the class clown and rising social media star with the big heart; and Ming (Tricia Tan, a revelation in her stage debut), the prickly rebel with an inferiority complex and an electric literary charge.

The 15-year-olds, from a range of familial and socioeconomic backgrounds, are about to undergo a series of gruelling examinations that will decide if they get “promoted” to Secondary Four, or if they’ll have to repeat the year. weish sets up the musical so that we see both teachers and students battling themselves and each other, when they’re really on the same team.

In Malay and Indonesian, lilin can mean a candle or its wax, and our protagonist and puteri lilin is melting from burning her candle at both ends. The path to burnout, in the case of the educator with the saviour complex, is paved with empathy, altruism, guilt, obligation and the unfounded belief that their way of caring is the only way to care—or that they’re the only one caring. Aiya. Lilin has one foot out the door of the fictional Huxley Secondary School. She’s one teaching observation away from the promise of the education ministry’s headquarters, or HQ, the promise of infiltrating a larger institution to implement the broad-based curricular and cultural change she now only dreams of.

But can Lilin change the machinations of a ministry when she can’t even wrangle change in her own school? It’s “cruel optimism” that keeps Lilin going, in the words of Lauren Berlant, the literary scholar who coined the term to describe what happens when your desire for the good life becomes detrimental to your flourishing. Aiya, if only I could get that promotion, that ministry posting, that cohort of students, I’ll finally be happy. It’s cruel optimism that keeps Lilin’s escape hatch jammed open. Just one more semester, just one more batch of students, just let me see them through their N-Level exams. Lilin gets to opt out. Her students don’t.

On paper (on paper)

On paper (on paper)

On paper we tell a child what they’re worth

Corrie's playlist

The musical joins a raft of productions stripping bare the pressure cooker machinery of Singapore’s education system. Haresh Sharma’s “Those Who Can’t, Teach” (1990), which has had several popular revivals over the past decade, also sees secondary school teachers as disillusioned bureaucrats who equate risk aversion with organisational accountability. The system they end up serving pushes a fiction of meritocracy to the students they started out wanting to serve. This is also the case for Faith Ng’s beloved and tragic “Normal” (2015), which has joined the ranks of Checkpoint Theatre’s repertoire. More recently, Michelle Tan’s “The Radicalisation of Mrs Mary Lim-Rodrigues” (2024) flays the studied stoicism of the veteran educator, and shows how calls to nurture “the whole child” may still fail teens who resist categorisation and teachers who, in trying to protect their hearts, realise they’ve forgotten how to feel.

This proliferation of plays about surviving formal education in Singapore should tell us where its pathology lies. In an interview with Vogue Singapore just before the show’s premiere, weish was frank about how the musical captures a particular slice of secondary school life from her teaching years in the mid-2010s, and that policies and cultures have undergone both substantial and subtle shifts over the past decade, for better and for worse: “Some of the structures [the musical] comments on are slightly outdated, but I can only write from what I know, and I feel like—from the conversations I’ve had with teachers still teaching—the spirit of the issues still remain today.”

“Secondary” does for the Singapore education play what Lin-Manuel Miranda’s blockbuster “Hamilton” did for the American history play. “…it’s nothing like the kind of music you would expect in a musical,” weish told Vogue. I watched the musical on opening night, when weish stepped into her own shoes as Lilin, replacing lead Genevieve Tan (recovering from a vocal injury). This verisimilitude—the former literature teacher playing a version she’d written of herself—didn’t escape me. Every crack and rasp in weish’s diaphanous voice, one that can go from Billie Eilish whisper to Broadway belt in a single stanza, felt like an emotional echo from that period of time in her life. What we’ve come to expect from weish in her own genre-bending, form defying musical practice are polyvocal live loops, synths and 808s, deliberate dissonance, haunting harmonies, the voice as a percussion and the breath as punctuation.

With the producing power and polish of Checkpoint Theatre behind her, weish has an entire ensemble at her disposal, a musical and vocal playground populated by an upcoming generation of triple threats. weish’s composing, script and musical direction are given sensitive shape by director Huzir Sulaiman who, together with his wife and creative partner Claire Wong, is no stranger to the dramatic architecture of both intimate two-handers and sprawling ensembles with complex, multi-character story arcs.

Here, Lilin marshals her educator skill set in the form of anthropomorphic affects a la Disney-Pixar’s Inside Out. They unfurl around her, a brigade of wayward scouts, all berets and blazers: Empathy, Cynicism, Optimism, Humour, Discipline—and Panic. Each has a different strategy, and it’s hard to get the combinations and percentages just right. When do you need more Empathy and less Discipline, or the catalysing force of Panic that conjures up a bit of surprising Humour? When you’re sitting across an at-risk student, with five minutes between meetings, the situation is less therapy and more triage. We’re not doing pastoral care, we’re doing critical care.

Hang on for just a while more

I’m less than well rested and far from my best

But it’s just for the rest of the year

Then I’m out of here

Different educators will have different approaches for keeping burnout at bay. Max Tan’s astute costume design becomes a visual shorthand for each character. Literature teacher Lilin wears New Balance 327s, telegraphing her elder millennial aesthetic with impractical suede and a chunky gum sole. Seasoned mathematics teacher Charlie wears Asics: practical arch and ankle support for long-standing teachers. Not everyone takes literature, but everyone takes maths, which means hours at the whiteboard. Head of department Mandy’s uniform is ankle-length dresses and sensible black pumps. Long-suffering style for the disciplinarian who doesn’t suffer fools gladly.

“I care until 6pm!” is Charlie’s formula. You know that maths teacher. He doesn’t quite care if you’re in the audience or not. You’re there as a repository for information, and a receptacle for dad jokes. He ducks responsibilities and dodges questions by taichi-ing them away: “What do you think? What do you think?” His monologue is one of the musical’s most side-splitting stand-up moments, and Malaysian actor Jun Vinh Teoh, with his kinetic physical comedy, is terrific as the collective embodiment of all patient, paternal “uncle” teachers in their checked shirts and outsized slacks.

Then there’s the glacial Mandy (a stunning Rebekah Sangeetha Dorai). Icy and immoveable, she’s sheathed herself in emotional armour and trained herself to break glass ceilings and push paper in the most efficient and effective ways possible. Someone has to keep the school going, and she is that someone. Lilin, fuelled by an early-career zeal, comes alive in the classroom when she’s invigorated by the possibilities of literary worldbuilding. She deflates almost immediately after as she wades through the trenches of bureaucracy and administration. The two women find themselves constantly at odds, butting heads over hearts.

None of their approaches work; or at least none work in isolation. The “brave new world” they’re constructing for the appropriately named Huxley Secondary School mistakes hierarchy for parity, meritocracy for fairness, categorisation for belonging.

I’ve sat in a few marks moderation meetings, and even when we’re referring to robust rubrics for each examination, the way we interpret them for each student sometimes feels completely arbitrary—because of, and also in Huxley’s case, the imposition of the dreaded “bell curve” that massages students’ grades in relation to others to fit a small minority of As and Fs, and a majority of Bs to Es. Last year, a member of Parliament asked the education minister Chan Chun Sing if our national O- and A-Level examinations were subject to the same bell curve. His response: “The grades awarded reflect a candidate’s level of mastery in a subject based on an absolute set of standards. They are not affected by the performance of others.”

The performance of others, unfortunately, directly affects our teenage friends and becomes a festering source of friction between them. Who’s included and rewarded by our education system—and who gets left behind? During these crucial years of identity formation, we learn that our self-worth is calculated by our academic success, and shackled to our use value and exchange value to a hypercapitalist state that stubs out our voices and paves over our desire paths.

The three students are grappling with familial and personal circumstances that no secondary school curriculum can equip them for, and are quickly realising how ironic their subjects are: in literature, they reckon with the false promises of their pseudo-utopian nation-state lurking beneath its scripted success stories; in mathematics, they discover there is no rational way to resolve the numbers they’ve always assumed followed a certain logic.

Funny how 55 and 54 are kinda the same score

But it changes who the teachers wanna check on

Just like 49 and 50 is the line they draw

If you graduate from Sec 3 onto Sec 4

It’s in the musical’s climactic number, “House”, where all of these strands—cultivating a voice, figuring an identity, carving out a space—coalesce. This is Tricia Tan’s star turn as Ming, whose facade of spiky teen angst obscures her fierce loyalty to her friends and the startling potency of her writing. Ming, resembling the thorny, poetically promising highschooler Maeve Wiley in Netflix’s Sex Education, is navigating her independence and autonomy as a young woman—even as her family depletes her emotional and mental resources as their main caregiver, and her coddling teacher Lilin makes naive assumptions about what’s best for her student. Ming yearns to be understood, but she doesn’t know how to ask for what she wants, and her teachers—initially, at least—don’t have the energy or focus to figure out what she needs.

Part of the musical’s brilliance is how the narrative’s metaphors play out as musical motifs. Each song is threaded through with carefully plotted polyvocalities; there might be a main melodic line with dissonant, syncopated harmonies churning underneath, complicating the emotional resolution of each piece. Often, weish will have her singers bend into keywords, muddling major and minor keys to deliciously discordant effect. “I lay-ay my head, I lay-ay my head,” they sing on “House”, with its relentless drum backbone laid down by Cheryl Ong, the percussionist and rhythmic heartbeat of iconic local band The Observatory.

There’s an extraordinary video weish recorded in her early days of taming this beast of a song. Her ethereal voice is ragged because the phrasing, pitch and scansion of each line requires the precision and breathwork of a military drill sergeant and navy diver. She’s taking in huge gulps of air to get to the end of every phrase. There’s no ensemble to loop the chorus for her, just her own voice. “House” is an urgent, impassioned plea of a song, carried by Ming when she realises, devastated, that she’s going to have to repeat the year.

Can we rebel and still be held by

this house that you call ours?

Can we be wrong and still belong

to this home you built for us?

Is there room for all of us in these walls?

How might we build a home in a caring democracy that has room for us all? Joan Tronto, the political scientist who’s devoted her research to the ethics of care in political theory, argues that it is our duty to invest time and energy in fellow citizens so that we can understand our caring responsibilities to each other. Her peer Jorma Heier, also a political theorist, takes this a step further.

Citizens and polities, she argues, wouldn’t exist without individual and collective care relationships. The “democratic caring with” that Tronto advocates requires knowledge about the lives of others, especially knowledge free of prejudice and misconceptions. A system isn’t an individual, but individuals make systems.

This is Lilin’s stumbling block. With her indulgent altruism, she forgets that education isn’t the role of one individual, no matter how competent or capacious. A wiser, senior educator once gently corrected me after I’d referred to a cohort repeatedly as my students. “The students are our students,” she said, “they don’t just belong to you.” The musical shows us that it’s ultimately the collective effort of both faculty and students that gets Ming through to the next year, and not Lilin alone. A musical isn’t a single person, and an education isn’t shouldered by a single teacher.

At the same time, when genuine attempts at “care” enter these systems, institutions and states, these “caring” aspirations can also deform and deteriorate. Charlie wants to offer Ming extra mathematics tutoring outside of school hours; Lilin wants to nominate her for a poetry prize that might propel not just her profile but her self-confidence. None of these strategies fit the school’s system of reward and punishment, especially when it comes to a troubled student with no academic “track record”.

One of the few people who operates outside of this system is Cik Sya (a truly versatile Nadya Zaheer), the school janitor—a brown woman adept at care labour who is, throughout the musical, relied on to intervene, uplift and nurture the school’s young charges through words and through food. The politics of race gets murky here, especially when Cik Sya shows up, with all her folksy wisdom and near-magical timing, to offer care and advice to the Anglophone Chinese teacher who thinks she can solve it all. Adel Kim, curator and researcher, has written about how personalised acts of care—so contingent on context—may lose their specificity and radicality when shoehorned into the rigid boundaries of organisational and institutional structures.

I’m floored by the ambition of “Secondary”, and weish’s uncanny ability to both introduce and accumulate insight about formal education in ways that allow us to both confront and repair this rite of passage for Singaporean teens. The musical’s three-hour runtime, intimidating at the outset, eventually feels surprisingly brief. It’s also why I feel hesitant about demanding the intricacies of fully fleshed circumstances for every character in ways that might still fit the musical’s sprawling ambit while maintaining its taut structure. But we do inhabit an intersectional space, and it’s the shared and collective responsibility of the artwork that creates a representational space about Singapore to be attentive to these abrasions and contradictions.

What is a voice

But to make your own meaning

Make your own choices

Raise your own ceiling

Like the lone leafy sapling on stage, “Secondary” offers the shade of its care to generations of students who were pruned to fit a monocrop mould, who were funnelled from one institution and examination to the next in the sterile clinic of educational diagnosis. Together, Checkpoint Theatre and weish offer us a triage of the education system that isn’t about “curative violence”, a phrase coined by Eunjung Kim in her seminal book exploring disability, gender and sexuality in South Korea. The professor of disability studies interrogates the dark side of the medical and social insistence on “curing”, where well-meaning attempts at curing or eliminating disability may end up risking unwanted changes, even death—rather than reconfiguring the demands of society to embrace and accommodate the variety of bodies, both able and disabled, that inhabit it. She cites the Sino-Korean word for cure and healing, ch’iyu (治癒), which combines the words “to govern” (治) and “to cure” (癒). To cure becomes synonymous with governing the body and its social relations.

“Secondary” does something radical: it decides it won’t cure or diagnose or test or solve us. Instead, it holds us, and really is a plea for an ethics of care to take root in the school system before primary care becomes palliative care. As Lilin stands on the cusp of another cycle of the school year (“aiya”), we wonder what decision she’ll take. The musical doesn’t offer us any easy antidotes to the blight of mental health besetting both students and teachers.

But that’s what care is, really. There’s no fixed and final cure that will get us over and done with care. In a country ridden with abbreviations, acronyms and other asymptotes towards hyper-efficiency, this is one of the things we’ve never learned: there’s no cure-all. Care demands both constancy and consistency, and it demands that we all do it together.

In memoriam: rising star Shahid Nasheer, who died of complications from leukaemia, age 28, on 14 October 2024.

Click here to experience the music of Checkpoint Theatre, curated by Corrie Tan.

Corrie is Jom’s arts editor. This essay was completed under the 2024 ArtsEquator Fellowship, and first published in Jom’s annual print magazine issue No. 2, released last year. Letters in response to this piece can be sent to arts@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

Read all of Corrie’s essays for Jom here.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.