The following few words of remembrance are a poor substitute for a “good-bye” in person; I am bereft.

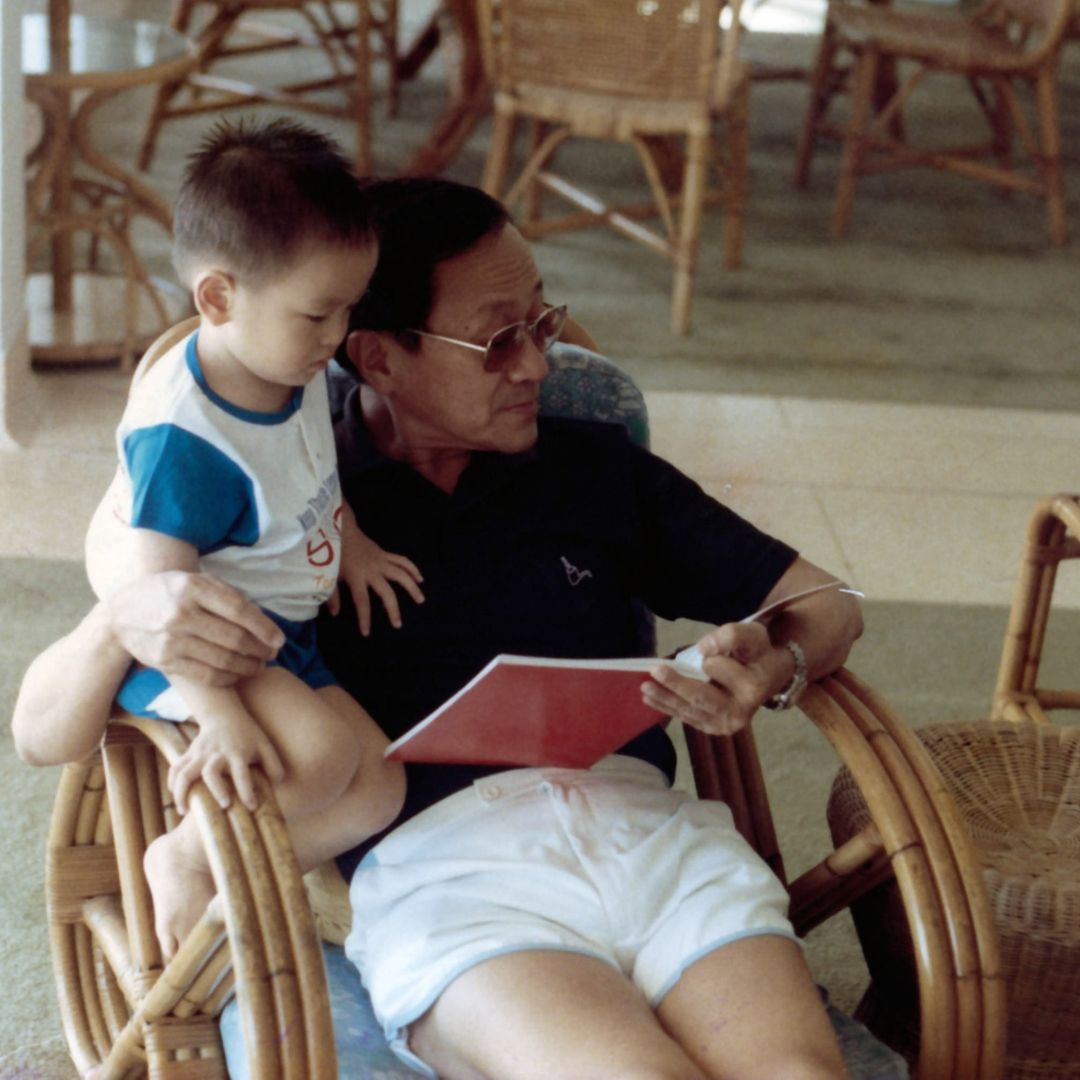

There was always a thermos of coffee. My earliest memories of my father were from the time we were living in Oxford in the early 1960s when Dad was working on his doctorate (DPhil) at Oxford University. He would drink copious amounts of coffee as he worked—reading, thinking, writing. Dad was a labour economist.

It was a period of discovery and delight for me. At school I was absorbing spoken English like a sponge; we spoke a lot of dialect at home in those days. Every now and then when I came in from exploring the melodious plot of beechen green behind our home on Boar’s Hill Oxford I would interrupt Dad and his coffee and his work. He always had time for me. I was his first-born of four children, two boys and two girls, and Dad called me his “diamond”. He patiently taught me to read, and opened up magical windows to the world:

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

This has been an enduring gift, as I have enjoyed reading both for work and for pleasure ever after.

Dad grew up in Malacca and we were Malaysian citizens. When we returned to Kuala Lumpur, Dad registered me at a nearby primary school. I was miserable and bored to tears. Miserable because I sounded so different from the other children so they teased me mercilessly as little children are wont to do, and bored as nothing seemed to be taught. Dad, ever my hero, sprung to action. I was moved to Assunta Convent, and I have no idea what he told the nuns, but I experienced no more teasing.

Dad drove me to and from school every day and we always had long conversations each way. He listened and encouraged. He talked about integrity and values, work ethic, drive, determination, discipline, motivation, focus and accomplishment, about doing something with one’s life. He recounted his own growing up, which was incredibly hard, what it was like to grow up without parents, without any money, and what a struggle it was to stay in school, of his many escapades including selling contraband cigarettes and ending up in jail. Yet, this was never recounted to gain sympathy. More importantly, I think it is what helped define his empathy for the poor and underprivileged. Perhaps it was also why he became a proponent of a minimum wage for workers in Singapore, a courageous position facing fearful odds given the entrenched political orthodoxy.

He also discussed his research and work at the University of Malaya, Malaysian politics, world affairs, and much else. It was only decades later that I realised what a privilege it was to have been his confidant, and how much those conversations also shaped me.

It was because of Dad that I joined the Girl Guides—something I would not have done on my own given my bookish inclinations. Growing up, he struggled to scrounge enough to even buy his school uniform, and often turned up for school without shoes. He wanted to be a Boy Scout, but trying to make pennies to keep from being hungry, and not being able to afford a Boy Scout uniform put paid to that dream. I think he derived vicarious pleasure listening to detailed recounts of my Girl Guides’ hikes and camping trips in the fields and under the sky.

It was also because of Dad that I became a school debater. Our car rides had long turned into debates. He encouraged questioning and critical thinking, the ability to be informed and then form and argue a point of view, plus the recognition that others could have valid different views that should be heard and respected. Dad was ever a diplomat and a gentleman, never the sort who would go for the jugular.

Dad was also the unhesitating Good Samaritan. Many, many years ago, on his way to pick me up, Dad witnessed a serious hit-and-run accident. He realised the injuries were grave and that there was a desperate need to get the victims to the hospital as quickly as possible. He swooped them into his car and rushed them to the hospital. The inside of his car was soaked in blood. He ended up being detained at the hospital, because they mistakenly thought that he might have been the person who had done the running down! It did not matter to him; he was always quick to do the right thing.

Like many parents, he wanted to keep his daughter at home for university. But I was ready to be stretched intellectually. I owe him a debt of gratitude that he agreed to let me go and did not articulate his great fear that his daughter would marry “out” and not come home. So, however much my world was opening up at university abroad, however many new friends I was making, however much fun I was having, I knew that I needed to repay that liberation by graduating with top grades, because that mattered much to him, and to return home.

Dad loved poetry—the rhyme and the reason, the metaphor and the metre, the messages and meaning, the cadence as well as the economy of expression. He loved reading poetry, and sometimes writing his own. My father’s favourite poem, which he and I can recite by heart, is “A Psalm of Life” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us, then, be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

Lee Suet Fern graduated from Cambridge University with a double first in law, and has had a successful career as an international corporate lawyer, winning many global professional awards. She was president of the Inter-Pacific Bar Association, and in Singapore, chair of the Asian Civilisations Museum and on the Senate and Executive Committee of the Singapore Academy of Law. She also sits on multinational corporate and not-for-profit boards.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.