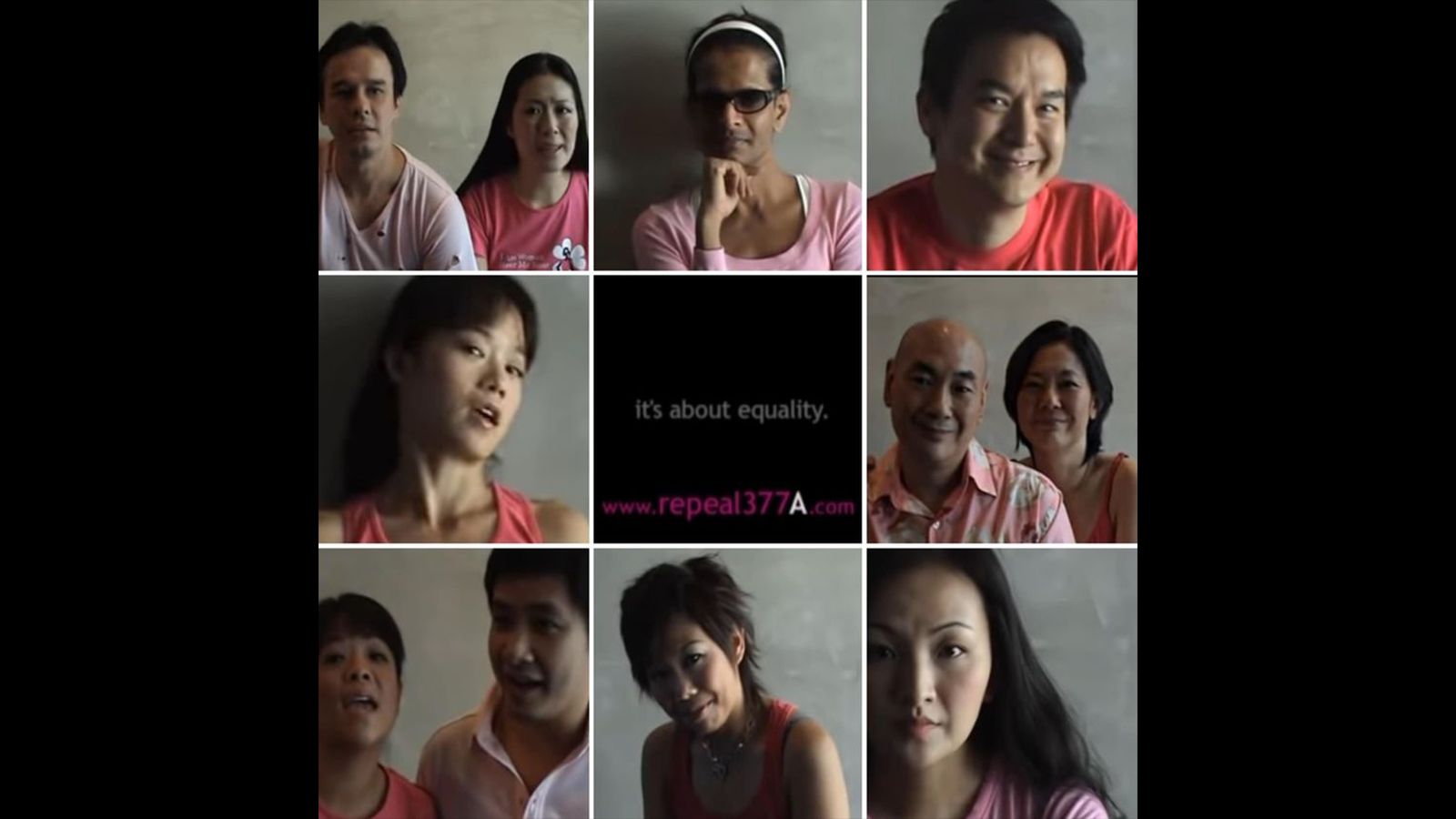

For decades gay people have been persecuted in Singapore. In the 1990s, Singaporean cops conducted sting operations to attract and catch gay men. In recent times, overt persecution has declined but the subtler, arguably more pernicious everyday forms have persisted: the workplace discrimination, the jokes, slights and micro-aggressions, and the glares from passers-by indoctrinated by a heteronormative state ideology that bars normal depictions of queer couples.

They are the other.

Underpinning this prejudice has been S377A, the colonial-era law that criminalises sex between men. Though rarely enforced, its presence impinges on the safety felt by gay men, preventing many from living their lives to the fullest.

The recent announcement that it will soon be repealed is thus cause for celebration. Yet societal attitudes towards the queer community will not change overnight. It takes time to unlearn prejudice and bigotry. Worryingly, the manner in which the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) has enacted the change, including its efforts to placate religious conservatives who want to further entrench heteronormativity, suggests that the celebrations ought to be muted.

Like a referee comforting a fallen fighter, the government immediately issued assurances that school curriculums and media content will continue to prohibit the acceptance of the queer community. Earlier this year, Singapore was the only rich, secular country to restrict the release of Pixar’s “Lightyear”, because of a one-second kiss between two women. Breathe easy, parents: your impressionable kids will still be shielded from such obscenities.

They are the other.

The PAP, with a supermajority in parliament, also announced its intention to amend the Constitution to give parliament the power to define marriage. This is apparently to stave off further potential constitutional challenges by gay rights activists, as happened with S377A.

The PAP wants to repeal it now mostly because it appeared like the courts might soon rule it unconstitutional (according to the equal protection guarantee under Article 12). In other words, the repeal is less about equality and more about opportunism.

Simultaneously amending the Constitution will allow the PAP to shift the decision-making power on marriage, which it fears is the next battleground, from the courts to parliament. The PAP’s reasons for doing so are unconvincing. Lee Hsien Loong, the prime minister, said that Singapore’s courts have neither the expertise nor the mandate “…to rule on social norms and values because these are fundamentally not legal problems, but political issues.”

We beg to differ. The freedom to love and enter into a union are human rights issues. They have both legal and political dimensions, and Singapore’s judiciary has the expertise and the mandate.

Lee, who was deputy prime minister during the 1990s' sting operations, also said that if change happens through litigation in the courts, it will “highlight differences, inflame tensions and polarise society.” But there is no reason why change will be less contentious if it occurs through parliament. Singaporeans, law abiding to a fault, are probably more united in their respect for a judicial process than any political one.

The proposed amendment is the latest in a series of manoeuvres—including the recent POFMA and FICA bills—through which power has been further concentrated in the hands of politicians, all under the guise that the judicial process is sub-optimal. The PAP is setting a dangerous precedent, again changing the Constitution willy-nilly, as if it’s playdough rather than a sacred document. Future governments may also seek to insulate inconvenient issues from pesky judges.

In supporting the PAP’s decision to avoid the judicial process on such issues, Eugene Tan, an associate professor of law at the Singapore Management University, wrote that “…if S377A is found to infringe Article 12, then other laws and policies that ostensibly differentiate on the basis of sexual orientation or sexual preferences could be unlawful.”

Errr, yes. They very well could be. Isn’t that what we as a society must unearth and correct?

Maybe not. They are the other.

A related concern is ideological capture. Religious impulses are perhaps in Singapore more easily transmitted through politicians than judges. Singapore, a secular state, currently has a religiously influenced definition of legal unions (as do most countries). The PAP has no intention of changing it, which reflects religious instincts (sometimes euphemistically called "traditional" values). Secular doctrines, by contrast, do not seek to narrowly define unions.

Given the current state of affairs, Singaporeans must collectively decide how we want to guarantee equal rights—including on adoption, housing and healthcare—to different kinds of partnerships and parents, such as single mums.

Finally, the way the entire public discourse around this issue has been stage-managed is an affront to the norms of a democratic, thinking society. Like in the past, it appears as if a high-level backroom decision was first made by ageing patriarchs, which was then followed by supposed public consultation. Suitable representatives from the different communities have been trotted out in succession to offer a glint of rainbow communality to the top-down diktat.

On Sunday morning, hours before the announcement, The Straits Times (ST) published an effective vote of confidence from religious leaders. In the weeks prior, ST succumbed to horrific bothsidesism, showcasing bigoted views from conservatives against repeal. This bothsidesism has this week been reinforced by K Shanmugam, the home affairs and law minister.

On the one hand, in supporting repeal, he said that “Nobody deserves to be stigmatised because of their sexual orientation.” On the other hand, he also argues that conservatives who are in favour of S377A—those who believe that sex between men should remain a crime—must be allowed to air their views freely in public without fear.

How can Singapore protect one group from stigmatisation if religious leaders are allowed to publicly call them criminals? We agree with Shanmugam that the wanton shaming of people with different views is wrong. But that does not mean that society must permit public bigotry.

This alludes to the most troubling aspect of the entire process. The public is given the illusion that diverse views are being entertained, yet in truth the conversation’s parameters have already been undemocratically defined by hegemonic power structures. Who gets to decide? How influential are religious conservatives among the leadership?

We will never know. Meanwhile, the PAP has again marshalled the bogeyman of social strife as a way to incite fear and obtain submission. Open debate without its paternalism and watchful eye will lead to ethnic tensions. That was yesterday’s news. This week we are led to believe that priests in frocks and gays in spandex are at each other’s throats.

The PAP may have wanted to heal divides but instead it has drawn battle lines. Genuine bottom-up dialogue will not occur. The party will mediate all. And if recent history is anything to go by, we know what message will filter down.

They are the other.

This editorial is from Jom's team. If you enjoy our work, do get a paid subscription today, and support independent journalism.