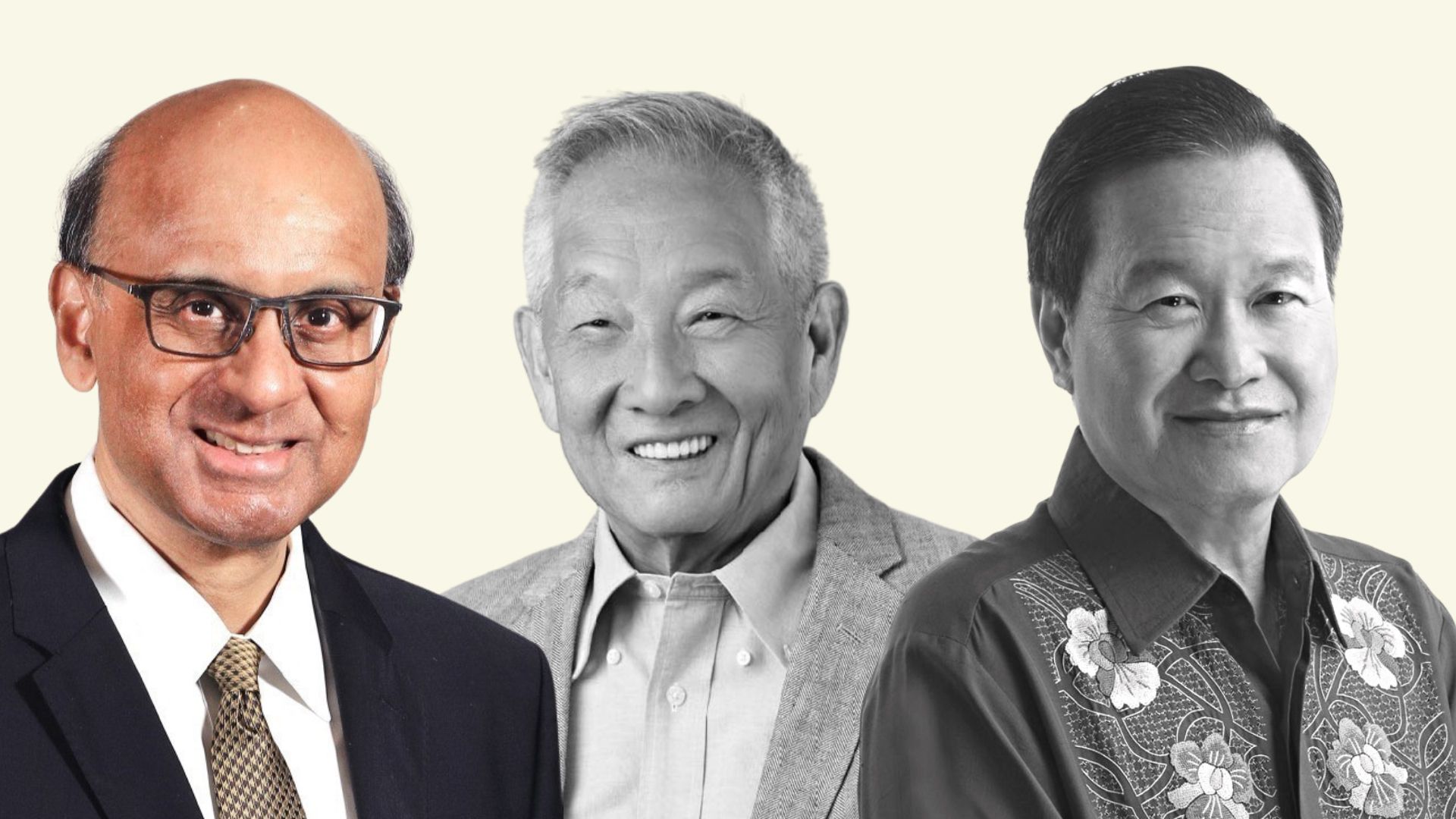

On Friday, Singaporeans elect a new president from the three people the government has deemed fit to run: Ng Kok Song, former GIC chief investment officer (CIO), Tan Kin Lian, former boss of NTUC Income, and Tharman Shanmugaratnam, former senior minister with the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP).

If character, competence and experience were the yardsticks by which voters choose, Tharman, respected across the political spectrum, would be a shoo-in. That he isn’t speaks to several issues with this problematic office, including its troubling origins in Lee Kuan Yew’s paranoia about losing power; the undemocratic and sometimes opaque nature of the qualifying process; the ambiguities about the role; the misalignment in expectations about the role between the establishment and the electorate; and the relentless tinkering by the PAP over the decades with the qualifying criteria, seemingly to install politically aligned presidents.

All this has caused among the electorate deep disillusionment with the elected presidency. Many generally regard it as a frivolous exercise. For some, it’s a chance to cast a protest vote against the PAP. This year, a “spoil vote” movement has emerged. Despite some enthusiasm about overseas Singaporeans being able to vote by post for the first time, Friday’s election is in many ways less a celebration of democracy than an obligatory ritual. It’s important to understand the origins of this apathy before assessing the three candidates.

Before 1991, Parliament appointed Singapore’s president, who served as a ceremonial head of state. The genesis of the elected presidency can be traced to 1981, when JB Jeyaretnam of the Workers’ Party (WP) won a by-election and broke the PAP’s 14-year stranglehold of Parliament. This scared Lee Kuan Yew. In 1984, he worried about a “freak election” delivering to office free-spending charlatans, who might raid and deplete our reserves. That’s when he first mooted the idea of an elected president as a possible check on a rogue government.

Seven years later, the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1991 revamped the role, duties, and selection mechanism of Singapore’s presidency. Chief among these changes were the president’s new veto powers over the use of Singapore’s reserves and key public service appointments, and the need to elect the president so they have the mandate to do all that. Only those who’d held a senior position in government or led a big corporation would qualify automatically to run. Despite changes since then, those remain the core powers and the guiding philosophy for eligibility.

Given that incumbent Wee Kim Wee had two years left of his term, the first presidential election was held in 1993, pitting Ong Teng Cheong, a former deputy prime minister with the PAP, against Chua Kim Yeow, Singapore’s first auditor-general. The LA Times reported that Richard Hu, finance minister, persuaded Chua to run. So reluctant was Chua that he admitted that he was running out of a sense of “public duty”, and that he considered Ong “a far superior candidate”. The Straits Times (ST) published a letter from an irate citizen: “I am greatly dismayed and disappointed by Chua Kim Yeow’s approach to his candidacy for president.”

Even after endorsing his opponent, Chua still garnered 41.3 percent of the vote. A now-popular adage among establishment folk emerged: even if one puts up a monkey, they’ll still get 40 percent of the vote.

Further complications would follow for Lee, because the new president Ong—how dare he—actually tried to do his job. He wanted to understand the size of the reserves he was charged with protecting. In 1996, when Ong asked for a valuation of the state’s physical assets, the accountant-general irritated him by responding that it would take 56 man-years to compute. “Oftentimes, senior civil servants found him ‘a pest’ and told him that the scheme only required him to check ‘the bad guys’, not the current government,” wrote academics Cherian George and Kevin Tan in “Why Singapore’s next elected President should be one of its last”.

Ong fell out of favour with his former party colleagues. In declining to seek re-election in 1999, he spoke about a “long list” of problems he had faced as president. The government issued a point-by-point rebuttal. When Ong passed away in 2002, he received only a “state-assisted” funeral, not a full state funeral as other leaders, including his predecessor Wee, had enjoyed.

The treatment that Singapore’s very first elected president received did not bode well for the office. The second elected president, SR Nathan (1999-2011), elected twice in walkovers, downplayed the office’s discretionary powers given that there was, in his view, a good government in charge. In 2011, amid broader political liberalisation, another problem emerged for the establishment.

Lee had believed that the stringent qualifying criteria would limit the presidency to figures friendly to the PAP, noted George and Tan. But he hadn’t counted on “breakaway establishment figures” vying for the role. The most important of these in 2011 was Tan Cheng Bock, a former PAP member of Parliament, and current chairman of the Progress Singapore Party, who ran against Tony Tan, the PAP’s preferred candidate, in an election featuring four Chinese men surnamed Tan.

Tony Tan won with 35.2 percent of the vote, with Tan Cheng Bock just 0.35 of a percentage point behind, with 34.85 percent. Tan Jee Say, a former civil servant, won 25.04 percent and Tan Kin Lian, a candidate this year too, won 4.91 percent.

With its preferred candidate having come within a whisker of losing in 2011, the PAP was shaken. A slew of constitutional changes followed ahead of the 2017 election. Most contentious was the affirmative action tweak: if a particular racial group had not been represented as president for five terms, or 30 years, then the subsequent presidential election would be open only to them. This effectively reserved the 2017 election for Malays. Critics perceived this move similarly to the creation of the Group Representation Constituency system in 1988—an attempt by the PAP to instrumentalise race for political gain. “Tan Cheng Block,” some cried.

The other important change was that private sector candidates henceforth had to lead companies with at least S$500m in shareholders’ equity to qualify, up from S$100m in paid-up capital. This change meant that both Farid Khan and Mohamed Salleh Marican, who may have easily qualified under 2011’s rules, were unable to do so in 2017. Likewise, for George Goh this year. Critics believe that all these changes make an institution that’s inherently undemocratic even more so. Based on minister Chan Chun Sing’s comments earlier this year, Jom calculated that only 0.044 percent of Singaporean adult citizens can easily qualify to run for president.

While the government accepted the Constitutional Commission’s recommendations in 2016 on tightening the criteria for the private sector, it rejected those for the public sector: minimum six years in a qualifying office. If it had also accepted that recommendation, Halimah wouldn’t have qualified—she’d been speaker for only four years. As it turned out, she was elected in a walkover.

This was the most questionable Singaporean election in recent memory, and not only because Tan Cheng Bock, Farid and Salleh couldn’t contest. Ugly complications emerged ahead of the election. Citizens learned that Halimah’s official race on her identity card is “Indian”, following her father. Yet, she claimed to be Malay and was accepted by the community as such. Interrogations into the salience of ethnic identities and classifications ensued online.

Many Singaporeans had by then been making genuine attempts to carve out space for granular meaning and identity within those broad yet limiting buckets, “Chinese”, “Malay”, “Indian” and “Others”. But the transactional way the PAP was seen to be treating race meant that public discourse was a reductionist one, about the PAP and Halimah’s perceived opportunism. It was often accompanied by racially charged terms, like makcik (auntie).

To rub salt in the wound, in Parliament in February 2017, Chan called Halimah, then speaker, “Madam President” twice. Many colleagues laughed along with him. This was months before Halimah had even confirmed she’d be standing for the election in September, and well before Farid and Salleh’s applications were considered. Senior PAP politicians appeared to possess some electoral clairvoyance.

One can trace a clear line of voter bewilderment from the apparent charade of the first election in 1993, and the problems Ong, a party stalwart, subsequently faced as first president, all the way to 2017, and the manner in which Halimah entered office. The elected presidency remains the largest constitutional amendment, having added 30 percent more content to the Constitution itself. Penat lah, tired, is how many Singaporeans feel about the whole show.

Even though Lee Kuan Yew envisioned the elected presidency as a possible check on a non-PAP profligate government, it’s evolved in a way that many citizens now see it as a potential check on PAP hegemony. This is the underlying reason why there is so much democratic dissonance leading up to it.

On the one side, establishment figures try to downplay the role’s significance, believing that the current PAP needs no check. On the other side, non-establishment folk often invest much hope in the independence of a non-PAP candidate, inflating the candidates’ own expectations of the office. “Do you want lower cost of living, lower cost of housing so you can get married and have children? If you do, please vote for me,” Tan Kin Lian bizarrely promised recently. There is a “lack of consensus about the rules of the race and the nature of the prize,” wrote George and Tan.

The person who perhaps has suffered the most is Halimah herself. An unassuming politician was tainted by scandal even before she entered office. She performed her core duties competently enough, including approving the unprecedented use of reserves during the Covid-19 pandemic. She offered an authoritative voice on efforts to promote gender diversity across sectors, and address racial discrimination in society.

Yet, instead of being remembered for her performance as Singapore’s first female president, Halimah will just as equally be regarded as a political tool. The fact that she didn’t stand for re-election this year, without any good reason, will entrench the idea that she was disposable to the party. Instead, in June, the party endorsed Tharman, the biggest gun of all. A foregone conclusion, many thought. Who’d stand a chance against him?

Two months on, Tharmanites are anxious. “This is so worrying. It confounds rationality,” one told me, in response to voters eager to cast a protest vote or spoil their vote. Nonetheless, as this person acknowledged, feelings are as important as rationality in assessing electoral choices anywhere.

For liberals, the disillusionment with Tharman stems from the persistent feeling that he’s not as progressive on socio-economic issues as they want him to be. This has its roots in the late 1970s and 1980s, and the hope invested in Tharman, the young student activist and leftist. “The sharpest mind of our generation”, as KC Chew, Tharman’s friend since secondary school, told Jom.

That generation’s desire for socio-political liberalisation would be rudely halted by 1987’s Operation Spectrum, when the government arrested and detained without trial 22 church workers, opposition volunteers, and activists, including Chew, claiming they were “Marxist conspirators” plotting to overthrow the state.

While many remained outside the system, Tharman went on to enjoy a long career in public service. He rose to managing director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) before resigning to join the PAP and stand for election in 2001. If this was perceived as him selling out, a month following the election Tharman, in an interview with ST, publicly stood up for his former leftist comrades who’d been arrested in 1987, saying that “...from what I knew of them, most were social activists but were not out to subvert the system.” (He’s done so recently again on the campaign trail.)

After entering politics, Tharman’s star continued to rise as he took on different portfolios: minister of education in 2003, minister of finance from 2007, deputy prime minister from 2011, and senior minister from 2019. In 2011, the International Monetary Fund appointed him chair of its International Monetary and Financial Committee, where he served for four years. In May 2015, Tharman won plaudits following a memorable interview with the BBC’s Stephen Sackur at the St Gallen Symposium. At the general election (GE) later that year, Tharman’s team won with 79.3 percent of the vote, higher than in any other district, including that of Lee Hsien Loong, the prime minister. The following year, Singaporeans who were surveyed picked him as their choice for next prime minister. (The party has always insisted that Singaporeans aren’t ready for a non-Chinese leader, a notion Tharman has just refuted.) With the benefit of hindsight, that period probably represented peak Tharman.

Since then, sentiment towards him, particularly from liberals and younger Singaporeans, has cooled. As high immigration and the rising cost of living have started to affect Singaporeans in different ways, people have become more critical of his complicity with PAP’s neoliberal economic orthodoxies, which continue to favour the interests of capital over labour. In a recent response to the issue of ferrying migrant workers by lorries, Tharman was adamant that the interests of businesses must be accommodated in the journey to safer transport—as opposed to supporting an outright ban, as many on the left want. His comments on the death penalty and LGBTQ rights mirror this slow approach. The pragmatist will disappoint those looking for a more urgent visionary.

In terms of his signature policies, Tharman is being ideologically outflanked on the left. Consider the Progressive Wage Model (PWM), which ties wage increases to the upgrading of skills (and works alongside initiatives like the Workfare Income Supplement). Though it’s helped nudge up wages, the PWM, critics say, works too slowly, is not well-enforced, and it hurts job mobility, because benefits are often linked to sector and employer. Tharman is sometimes compelled to defend it, most notably in 2020 in a debate with Jamus Lim of the WP, who was arguing for a minimum wage. “No one should assume that you have a monopoly over compassion,” Tharman snapped.

Though he’s one of Singapore’s most recognisable public figures, Tharman is, for the first time, having to engage in relentless self-promotion. Social media videos range from big picture issues (Singapore’s role on the global stage) to personal, offbeat remembrances (the role of orh nee, a Teochew yam dessert, in procreation). He’s also spoken about mental health, multiculturalism, the environment, and supporting people with special needs. His wife Jane Ittogi, who was also a student activist in London, where they met, often appears alongside him.

Tharman has been trying hard to distance himself from his party, emphasising his “independence of mind”, the fact that he’s resigned from the party, and that, as president, he can operate above politics. PAP loyalists will buy this, but for others, it’ll be a hard sell. Tharman, almost by definition, is seen as the candidate least independent from the party.

That said, some supporters believe that Tharman has been playing a long game, and that if elected, will go much further than previous presidents in terms of advocacy. He recently said: “I intend to be very supportive of initiatives on the ground, by civil society, by informal groups of people, even by the traditional organisations.” In a book review last week for Jom, 87-year-old Constance Singam, who’s been called the “mother of civil society”, struck a cautiously optimistic note: “I am excited about his idea of the third space to enable Singaporeans to participate in each other’s culture. But this will require Tharman to make good on his promise to involve civil society.”

The hero’s journey, then, is about the young activist subsumed into the system, only to re-emerge four decades later with knowledge of its inner workings, and a promise to energise the ground. Too much of a fairy tale? Perhaps, given the fundamental power dynamics in society. As president, Tharman will almost certainly disappoint his most quixotic fans.

Still, the chance that a Tharman presidency will usher in a socio-political environment more conducive to activists and critics may worry some in the PAP. In that sense, a safer bet for the party may be Ng Kok Song, GIC’s former chief investment officer (CIO), a “non-government-endorsed” establishment candidate.

When Ng first announced his intention to run, many were puzzled. Why the need for a second establishment candidate? One theory is that he was put up to it to ensure a contest for Tharman, as another walkover, after Halimah 2017, would sour the ground even more ahead of the next GE, which must be called by 2025. Ng, in this reading, is the 2023 incarnation of Chua Kim Yeow, who grudgingly stood against Ong Teng Cheong in 1993.

Another theory is that not all in the establishment support Tharman’s candidacy, a notion fuelled by the vociferous support Ng has received online from Ho Ching, former boss of Temasek (and the prime minister’s wife). An opposing theory is that introducing Ng will split the “anything but PAP” vote, giving Tharman an even better shot at success.

Regardless of whoever may (or may not) have prodded 75-year-old Ng, he, unlike Chua in 1993, is going for it. He’s eschewed traditional campaign posters and instead is mostly relying on social media. He’s been campaigning hard, supported by his fiancée Sybil Lau, 45. Early online comments lampooned their age gap. But it seems people have since warmed to Lau, after a series of videos featuring her, including one where she speaks about her purpose and interests in life, and admires Ng’s dedication to his late wife, who died from cancer in 2003.

If Tharman comes across as the erudite, Ng projects the image of a folksy grandpa who prioritises harmony and social cohesion. Unlike Tharman, whose father was a renowned pathologist, Ng wasn’t born into privilege. He grew up in the fishing village of Kangkar (where Sengkang is today). His father, a fish auctioneer, earned barely enough for the family, including Ng’s 10 siblings. He described an attempt by his mum to borrow money for his school books—ending in failure, and tears—as having inspired his desire to work hard.

Ng wants to be president to protect what he believes are the “three national treasures that define our country Singapore as exceptional”: its reserves, good public administration, and social stability. He began his career at the Ministry of Finance in 1970, joined GIC in 1986, and served as its first CIO from 2007-13. He has regularly cited this experience as proof of his familiarity with local and global economic issues, and thus his ability to discharge the president’s key duties, including holding the second key to our reserves. Of the three candidates, Ng seems to emphasise most the core, circumscribed role of the presidency, as Lee envisioned in 1991—and thus appears relatively less likely as president to promote other agendas or initiatives.

Ng’s also a mascot for active ageing. His video discussing his secret to staying fit at 75—Sleep, Handle stress, Interaction, Exercise, Learn, Diet (SHIELD)—has recorded over 3m views on TikTok. Yet other videos are far less flattering, including one that exposed his poor Mandarin skills. One broader challenge is that in his effort to portray himself as relevant and relatable to the younger generation, he sometimes goes too far, eliciting “wayang” and “cringe” comments.

Whether or not he feels more independent than Tharman from the establishment is unclear. In 2015, Ng co-founded Avanda Investment Management, an investment fund that’s heavily reliant on contributions from state-linked firms, including the Singapore Labour Foundation, Temasek and GIC. By 2022, Avanda managed over US$10bn (S$13.5bn) in assets. Other formal positions, including having served on the governing board of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, and informal ones, as meditation guru to Lee himself, along with Ho Ching’s regular words of support, suggest that Ng is a fully fledged member of Singapore Inc., and much closer to the powerful Lee family than Tharman’ll ever be.

By contrast the final candidate, Tan Kin Lian, despite being a PAP member till 2008, is seemingly the most independent of the establishment. His candidacy has, however, been tarnished by his troubling history of xenophobic and misogynistic posts.

Tan, like Ng, grew up in a low-income family dependent on the fishing industry. He started working after secondary school, he said, to help support the family, including his five siblings. He joined NTUC Income in 1977. The fledgling, seven-year-old organisation, appointed him, then aged 29, as CEO. He served for 30 years in that position. During that time, its asset base grew from S$40m to S$19bn. “He has almost single handedly made Income into a household name in Singapore,” said Tan Suee Chieh, his successor, in a welcome note in 2007. “The many strengths of Income are his [Tan Kin Lian’s] legacies to us.”

Tan’s messaging on the campaign trail suggests that he has an expansionist view of the president’s office. Aside from his aforementioned desire to help young couples secure affordable housing so that they can get married and have kids, he’s also spoken about addressing Singaporeans’ concerns over National Service and the management of their central provident fund savings. It’s doubtful that the president can ever have much influence on such policies, so Tan, if elected, may disappoint supporters.

Last week, the Elections Department and the Infocomm Media Development Authority forced Tan to remove “inaccuracies about the President’s role” from his broadcast speech. Separately, his gung-ho relationship with speech and facts was also highlighted in a “Yah Lah BUT” podcast. When asked if he had any lawyers advising him on the president’s office, Tan replied: “I don’t allow other people to tell me what to say. I know my job. And I know the law. I interpret the law quite differently from lawyers.”

He’s already shocked many liberals through his social media activity, including a long history of objectifying women. A few examples are illuminating. On November 23rd 2021, Tan posted a series of photos of “pretty girls” on a 4.17km walk. One photograph is a close-up of a woman’s bum exposed below her ripped denim shorts. One of his “Top fans” commented “Food eaten too good.” A follower responded with a “I like big butts and I cannot lie” GIF. On May 30th 2019, he conducted a social media poll: “If a girl wears revealing clothes and gets touched, who is at fault?” (Answers: either “The molester” or “The girl”.)

Alongside his popular “pretty girls” series is a xenophobic post from 2015. “I boarded SMRT 857 and found that I was in Mumbai. Hahaha,” he said, playing on Singaporeans’ resentment about recent high immigration from India. He took it down and apologised only to “local Indian friends who feel offended”, and not “...foreigners (who think they now own Singapore).” Last Friday, in a further appeal to nativists, he said that “locals” prefer the president and their spouse to be “true Singaporeans from birth”—a clear dig at foreign-born Lau and Ittogi.

Many, including the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE), have since questioned the work of the Presidential Elections Committee (PEC), which passed Tan as a “man of integrity, good character and reputation”. The PEC’s unsatisfactory response to the current furore is that it did not assess Tan’s social media posts before passing him, and is now legally bound to its decision. (The PEC previously passed him for the 2011 election, but that was before all these posts.) The ignorance of something as obvious as a person’s digital footprint is jarring for many voters—all the more given the decades-long moralising by the government about the need for stringent, qualifying criteria to ensure that only the purest can compete.

Tan, who has a history of banning critics from his pages, claimed that there was an orchestrated campaign involving AWARE and a “top opponent” (Tharman) to smear him, and then later admitted he had no evidence. His daughter came out in his defence. He has now claimed to “have great respect for Indians”. Notwithstanding the obvious differences between countries and offices, the parallels to Trumpian behaviour and rhetoric are clear. If his fans, including those who like his straight-talking style, carry him to office, people may be emboldened to indulge in bigoted speech. (Pretty girls in the Istana? He he he.)

Tan’s behaviour is a big reason why some people, who might otherwise have voted for the independent candidate, intend to spoil their votes. To be sure, the sense that he’s been victimised by the establishment and liberals has also drawn sympathy from fans. In any case, all this may not matter much to Tan, whose candidacy has been bolstered by a recent endorsement from Tan Cheng Bock and Tan Jee Say, two of his opponents in 2011. Others already in his camp include Lim Tean, leader of People’s Voice, and Iris Koh, founder of anti-vaccine group Healing the Divide.

Aside from their stated desire for a non-establishment president, it’s unclear why so many opposition leaders have come out in support of Tan Kin Lian—and what favours they might call in should he win. Tan Jee Say and Lim Tean have a history of nativist rhetoric and platforms. For Tan Cheng Bock, who has described the “pretty girls” saga as “gutter politics”, this endorsement may jeopardise future electoral support from liberals.

Ng has seized on this moment to position himself as the true “non-partisan”. Indeed, pre-election discourse suggests that voters are trying to make sense of each candidate’s relative independence. Tharman appears to have no more formal dependency on the establishment, but will always be associated with the PAP. Ng has never been in a political party, but the fund he co-founded is heavily dependent on the state. Tan Kin Lian has been a seemingly independent critic of the PAP for some time, but is now associated with some opposition figures.

The short campaign period, the deluge of social media videos, the scandals and rebuttals, and the flurry of recent endorsements, have all helped fuel this confusion about the candidates.

What does the electoral maths suggest ahead of Friday’s election? Even though election forecasting is a crapshoot anywhere, it’s worth assessing the available data points, most importantly the results of the 2011 presidential election: Tony Tan won with 35.2 percent; Tan Cheng Bock second with 34.85 percent; Tan Jee Say third with 25.04 percent; and Tan Kin Lian fourth with 4.91 percent.

For political analysts, these numbers shed some light on aggregate voting blocs: the “only PAP” die-hards perhaps make up about 35 percent of the electorate; and the “anything but PAP” segment—those who voted for Tan Jee Say and Tan Kin Lian—another 30-odd percent. (Tan Cheng Bock, in that election, was perceived as drawing support from across the political spectrum.)

This suggests that Tharman can be assured of at least 35 percent of the vote, while Tan Kin Lian will be hoping for at least 30 percent. That said, there’s only so much credence one can give to 12-year-old election results. In a sense, Friday’s result will update this barometer. Indeed, Ho Ching recently re-shared a post, awful in its elitism, which posited that “voting for TKL [Tan Kin Lian] is going to be a good gauge of the extent of insanity among the Singaporean public ahead of the next GE.”

Regardless of whom they’re voting for, the majority of Singaporeans are probably going to the polls on September 1st more with apathy and disgruntlement, than with any democratic exuberance. Unlike the GE, the presidential election has, for many Singaporeans, devolved into political charade. It has its origins in Lee Kuan Yew’s paranoia about a “freak election”, reflecting his worry that Singaporeans cannot be trusted to elect the government that best suits their needs.

This old assumption that the electorate is ill-informed, and needs to be shepherded towards the right choices, appears alive and well, if one looks at how the presidency has evolved since then, as well as particular remarks such as Chan Chun Sing’s “Madam President” in 2017. It’s probably unfathomable to the PAP that the electorate might one day actually want a government that spends a wee bit more of the country’s reserves, perhaps to mitigate the yawning inequalities in society. What the PAP views as “freak” may actually just be the peoples’ choice.

Elections in most democracies are usually opportunities for citizens to revel in the marvel of joint decision-making, of collective choice, of living in a system where citizens are empowered to choose their leaders. But Friday’s presidential election in Singapore will be a reminder mostly of how convoluted the practice of democracy here has become. And how that, itself, is a symptom of a rather depressing aspect of being Singaporean: our leaders simply don’t trust our judgement.

Sudhir Vadaketh is Jom’s editor-in-chief. Additional research by Liyana Batrisyia, Chang Zi Qian, Tim Chee and Arun Mohan.

If you enjoy Jom’s election coverage, do get a paid subscription today. Singapore’s general election is coming and Jom needs all the support we can get to cover it exhaustively, and produce this kind of slow journalism, which is editorially intensive. Thank you.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.