A “large majority” in regional cities agree Singapore’s death penalty deters serious crimes, screamed a CNA headline last month. It was referring to a survey by Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), just the latest purporting to support our use of the ultimate punishment for serious crimes.

Separately, Singapore’s new Parliament has just convened, comprised of two parties which support the death penalty. The main distinction between the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) and the opposition Workers’ Party (WP) is that the latter believes it should not be mandatory, arguing for greater judicial discretion in its application.

Jom, by contrast, has always been part of the seemingly small abolitionist camp. We have already expressed our position briefly in an essay on a WP candidate and in our weekly digest. But given the political and informational power dynamics at play today, we believe it’s important to more thoroughly engage with, and contribute to, the debate.

Readers may feel that there are more pressing issues for us to contend with, such as the cost of living; and may wonder about the potency of our arguments amidst serious public health concerns over drug-laced vapes. Yet each one of us is implicated in the death penalty—it’s our collective decision to end the life of another in the apparent pursuit of justice and safety. With numerous humans on death row, and more surely to join them, it’s hard to conceive of any issue more urgent.

Calling for the abolition of the death penalty should not be misconstrued as being “soft” on crime or lacking empathy for the victims of drug abuse (and other crimes). Too often, these things are lazily conflated, as if every abolitionist is some blinded libertarian who wants to defund the police and let junkies swap syringes in Seletar Park. No. We believe that Singapore can remain a safe place, and can reduce the harm drugs inflict on users, without the death penalty.

Many Singaporeans might instinctively disagree. While each is entitled to their view, we feel that many have not been adequately exposed to alternative arguments. Ours is an informational universe dominated by conservative forces, specifically the PAP and its obedient mainstream media. If taxpayer-funded outlets like CNA and The Straits Times, for instance, cared about providing you with a diversity of viewpoints, why don’t they publish commentaries from abolitionists? A legitimate viewpoint in other democracies is probably deemed dangerous in our “global” city.

This is the foundational problem with Singapore’s approach to the death penalty. For a society that prides itself on deep thought and analytical rigour, our common base of knowledge on the issue is shockingly hollow. It’s in that spirit of intellectual discovery that we seek a more honest conversation.

Generally, there are five motivations for punishing offenders: retribution (a wrongful act justifies proportionate punishment); incapacitation (removing a harmful actor from the community); deterrence (reducing an actor’s desire to commit harmful acts); rehabilitation (reforming a harmful actor) and restitution (perpetrator offering compensation to victims, perhaps financially). The relative emphasis on each in a criminal justice system reflects a society’s complex set of beliefs about human behaviour, including individual agency and circumstance.

Deterrence takes two forms. Punishment has a “general deterrence” effect on the public at large, and a “specific deterrence” effect on the individual offender. The common justification for retaining the death penalty, particularly for non-violent crimes, is general deterrence. But there’s no conclusive evidence that the death penalty deters crime any more than other forms of punishment, such as life imprisonment. It’s a subject not easily studied because there is a methodological challenge concerning the counterfactual: how do we assess crime rates for a particular jurisdiction over a specific period of time—say, Singapore from 2020 to 2025—both with and without the death penalty? There isn’t an intuitive experiment we can conduct.

Another problem concerns the assumption of rationality. Does a prospective criminal pause, and perform a cost-benefit analysis, before deciding whether to commit a crime? Are their expectations rational, in that they accurately perceive the sanctions risk they face? The “rational choice theory” is fiercely contested, not only for substance-soaked addicts whose faculties are compromised.

Still, over the years, criminologists, economists and others have tried, mostly focusing on the death penalty for murders in the US. These include regression analyses to estimate the impact of executions on the murder rate, some suggesting a “strong deterrent effect”; and comparisons of murder rates in US states (consistently lower in those without the death penalty than in those with). And so the evidence is mixed—some indicating a deterrent effect, others not. One common criticism of studies is that they isolate the impact of executions without accounting for lesser alternatives and other factors. How do we really know it was capital punishment? In 2009, a study published in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology found that 88 percent of criminologists surveyed did not believe that executions lower murder rates.

The same year, three American criminologists examined intentional homicide rates from 1973-2008 in Singapore and Hong Kong, which abolished capital punishment in 1993. “By comparing two closely matched places with huge contrasts in actual execution but no differences in homicide trends [emphasis ours], we have generated a unique test of the exuberant claims of deterrence that have been produced over the past decade in the US.” Researchers were looking to Asia’s two preeminent global cities, both former British colonies who’d inherited their laws—about as close to a geopolitical “twin study” as you’ll get—to inform domestic policy.

In 2012, the US’s National Research Council published an exhaustive review of three decades of research, “Deterrence and the death penalty”. It concluded that the research hitherto conducted “is not informative about whether capital punishment decreases, increases, or has no effect on homicide rates.” In other words, despite exhaustive long-term data and research, we still don’t know if the death penalty deters crime. The Council argued that such research “should not influence policy judgments about capital punishment.”

Singapore contributed to the global body of research in 2020, with “Deterrent Effect of Historical Amendments to Singapore’s Sanction Regime for Drug Trafficking”, which claims to represent “one of the first efforts in the empirical capital punishment literature to attempt to quantify the deterrent impact of the death penalty on drug trafficking.” It highlights the mandatory death penalty (MDP) amendments to Singapore’s Misuse of Drugs Act (MDA) over the decades.

| MDA Amendments | Date of Commencement | |

| 1975 | Mandatory death penalty introduced for the trafficking in more than 30g of morphine and 15g of diamorphine (or pure heroin). | Dec 12th 1975 |

| 1990 | Mandatory death penalty for trafficking of opium beyond 1,200g, cannabis beyond 500g, cannabis resin beyond 200g, and cocaine beyond 30g introduced. | Jan 15th 1990 |

| 1993 | Mandatory death penalty for trafficking in more than 1,000g of cannabis mixture introduced. | Dec 10th 1993 |

| 1998 | Mandatory death penalty for trafficking in more than 250g of methamphetamine introduced. | Jul 20th 1998 |

It sought to investigate if the introduction of the MDP reduced the likelihood that traffickers would traffic above the specified threshold and/or reduced the weight that traffickers chose to traffic for that drug type. It specifically examined the four-year window before and after the 1990 amendment, and concluded that “the introduction of the death penalty for the trafficking of cannabis and opium in 1990 likely had a deterrent effect on trafficking behaviour for these drug types.” Specifically, it said that “MDP for cannabis might have reduced the probability that cannabis traffickers would choose to traffic above the capital threshold for cannabis in the four years immediately following the change in the sanction regime by around 15 to 19 percentage points.” (The full methodology is in the paper.)

The first baffling thing about this study is simply its authorship and publication. It was conducted not by independent researchers or university academics, but by somebody in the research and statistics division at the MHA, under K Shanmugam. Next, it was not published in a leading international criminology journal, like so many others, but in the “Home Team Journal”, which is a publication by the Home Team Academy in collaboration with MHA and its departments. We don’t know if the author attempted to get it published in a proper journal, or the extent of the peer review process (MHA did not return a request for comment).

In 2023, Mai Sato, an associate professor at Monash University who focuses on the death penalty, wrote a detailed criticism of the MHA study in the appendix for “Singapore’s death penalty for drug trafficking: What the research says and doesn’t”, published on Academia SG. Sato, among other criticisms, noted several omissions, including, “...the number of convicted opium traffickers increased after the introduction of the mandatory death penalty, on which the study is silent in the main body of the article.”

She also took issue with the 15 percentage reduction data point, presented as statistically significant at the 10 percent level, without explaining why it deviated from the five percent norm. (In English, the MHA study used a more lax statistical level of confidence than is common in such research.) One of Sato’s criticisms is more intuitive. Recall, the MHA study looks at the impact of a new policy on criminal behaviour. But in (pre-Internet) 1990, what efforts were made to disseminate news about the MDP for cannabis and opium? Why do we assume that would-be traffickers, say impoverished addicts across the border, even knew about this change, and hence could be “deterred”? Unsurprisingly, one rarely hears about this MHA study in local discourse, never mind global. (Sato wrote that MHA declined to share the raw data with her. MHA did not return a request for comment on the validity of Sato’s overall critique.)

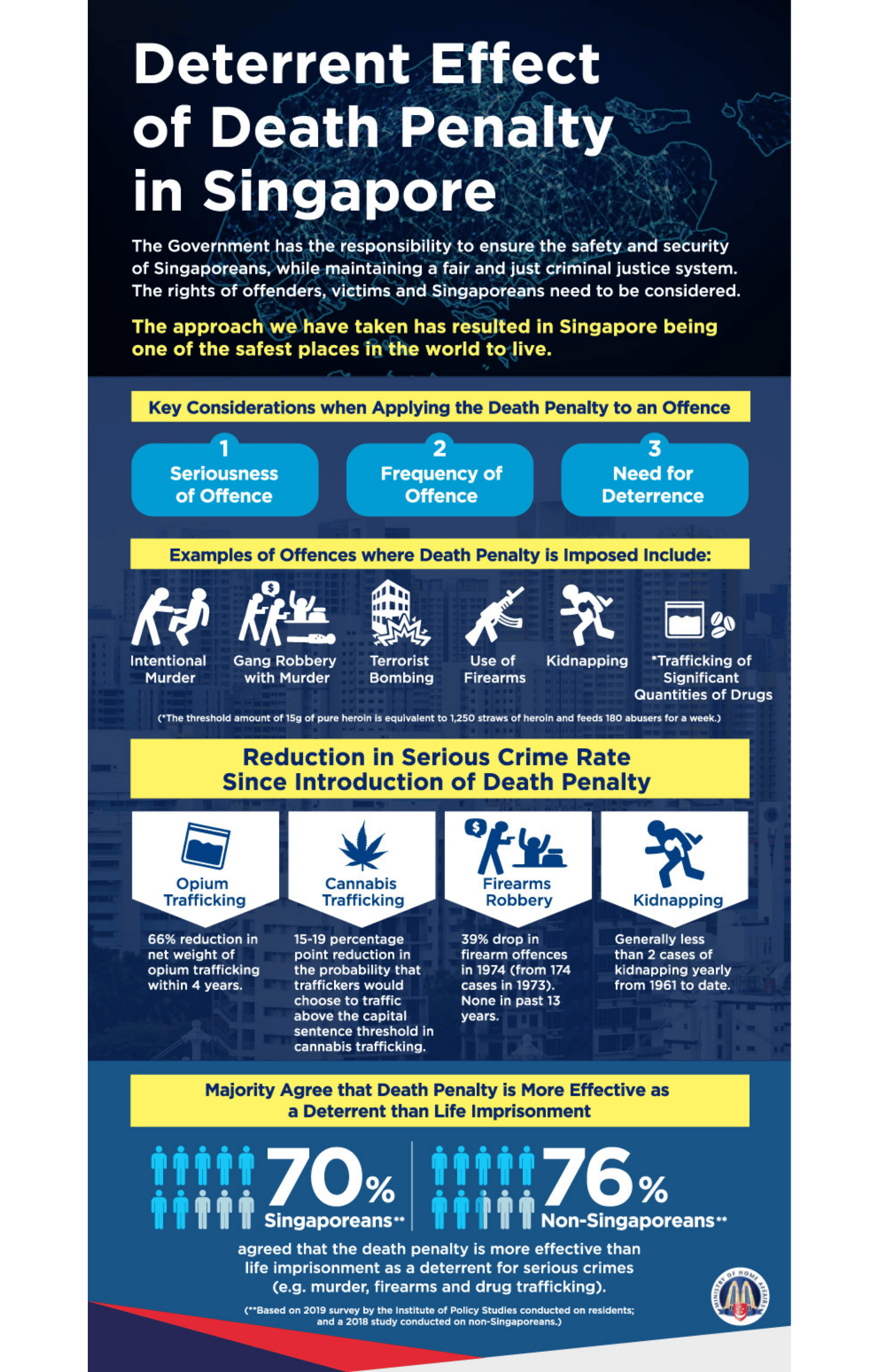

The “15 to 19” statistic did make its way, however, onto a MHA poster on deterrence (see below). On it, the MHA also noted reductions in serious crime rates and risks “since” the introduction of the death penalty, going back to kidnapping in the early 1960s. Notably, it did not say “because of” the death penalty. We simply don’t know. Causation is tricky to prove. As Lee Kuan Yew’s new government raised living standards and muscled its way through society, crippling triads and jailing political opponents, there were perhaps many reasons to explain these reductions.

Separately, in a post criticising the commuting of death sentences by Joe Biden, outgoing US president, Shanmugam lauded Singapore’s “tough approach”, relying partly on the fact that the number of drug abusers caught in Singapore has halved in the past 30-odd years. But that is a circumstantial data point that could be more correlation than causation. Daniel Nagin, criminologist and professor at Carnegie Mellon University, has argued that the certainty of being caught has a greater impact on deterrence than the severity of punishment. A qualitative MHA study, “The Impact of Deterrence on the Decision-Making Process of Drug Traffickers”, from the same 2020 paper, suggested similar. Is it really the death penalty that deters would-be traffickers from entering Singapore? Or more the fact that our efficient border security increases the certainty of being caught?

Absent solid evidence about deterrence, Singapore has generally instead relied on surveys to gauge societal attitudes towards the death penalty. For instance, MHA commissioned a 2022 survey by the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), a government-adjacent thinktank within NUS. It asked respondents for ratings on a Likert scale (Strongly agree -> Strongly disagree) for such statements:

- I support the death penalty in general.

- I believe that if the death penalty were imposed on more crimes, there would be fewer crimes.

- I believe that compared to life imprisonment, the death penalty is more effective in discouraging people from trafficking drugs into Singapore.

The recent survey of people in regional cities, also commissioned by MHA, similarly used a Likert scale for such statements:

- I believe people will likely be caught if they consumed drugs in Singapore

- I believe that the executions of drug traffickers in Singapore over the past year have deterred people from trafficking substantial amounts of drugs into Singapore

- I believe that the Singapore Courts act fairly

The results of such surveys generally reveal confidence in Singapore’s capital punishment regime, offering it legitimacy. But a critical analysis reveals problems with the survey approach, methodology, and the way it is deployed.

The base problem concerns incomplete information. Respondents simply don’t know enough about the death penalty to engage with such surveys. “Although the majority of citizens may support the death penalty, this may simply be because they have become socialised and conditioned to accept it as a legal and cultural norm, the justification for which they have barely considered further,” wrote Roger Hood, criminologist at the University of Oxford. “Indeed, they may base their views on misinformation and misconceptions about the administration of the death penalty.”

(The IPS study purported to show that Singaporeans are knowledgeable about the death penalty through a simple eight-question assessment, though it contained basic errors, as Sato noted; and in any case, some answers reveal quite appalling ignorance, for instance on the number of people killed every year.)

Studies around the world, such as “The Impact of Information on Death Penalty Support, Revisited”, have shown that when people learn more about the specifics of it, their support dwindles. A 2018 study by NUS corroborated this. When presented with three lifelike criminal examples that would warrant the mandatory death penalty, just five percent of the respondents who claimed to support it actually chose death in all scenarios. Support also drops if proven that it’s not a better deterrent than alternatives such as life imprisonment; or if it’s shown that innocent people have been executed.

A related issue is that on the Likert scale, the intensity of feeling is generally weak. Those who “strongly agree” or “strongly disagree” with statements about the death penalty, in other words, are in much smaller proportion to those with milder feelings, including neutrality. This suggests that their minds can be more easily changed with more complete information—which is precisely what we see with aforementioned studies.

A separate issue concerns whether the respondent sample is representative of a pool that includes would-be criminals. Shanmugam seems to think so. Last year, in the BBC podcast “Assignment: Singapore – drugs, rehab, execution”, one of the most telling bits involved the host pushing back on Shanmugam’s claim of a “huge deterrent effect”.

Linda Pressly: “I’m not sure that the deterrence argument is proven from what I’ve read about deterrence studies. The only studies I’ve seen that are done have been done about homicide in the United States. And they’ve found that actually when you take away the death penalty the number of homicides hasn’t increased.”

K Shanmugam: “Let me explain the deterrence effect. In 2021, we’ve done a study in the region from where many of our drug traffickers come, I think it’s about 83 percent, in the region say that the capital punishment is much more of a deterrent compared with life imprisonment in the context of drug trafficking.”

Pressly: “But that’s a perception though, isn’t it, in those regions.”

Shanmugam: “Oh, that’s very important.”

Pressly: “But if you’re talking about the theory of deterrence, it depends on rational decision-making. (Shanmugam: “Well, yes.”) So, often it’s drug users of many years standing who are being convicted on capital charges here in Singapore and I think we could probably agree that if you’ve been using heroin for 50 years you’re not actually going to be doing rational thinking very well.”

Shanmugam: “Well, let me come back to finish my point, which is that if there is that perception people know that it’s serious and people believe that it is more of a deterrent then many more who would be drug traffickers would be deterred.”

We disagree. Because what is the link between those who take surveys and actual criminals? Consider the recent survey of people in regional cities. Some 2,000 people from six cities—MHA has declined to name which—took the poll online. Let’s take pause. If a middle-class urbanite in (perhaps) Bangkok or KL believes that the death penalty deters drug trafficking into Singapore, does that make it true? Do they know how the destitute, vulnerable Thai or Malaysian drug mule perceives the death penalty? Or are they simply projecting their own ingrained beliefs?

“Politically, this finding may suffice to justify the retention of the death penalty to the Singaporean public,” Sato wrote, of an earlier regional survey. “However, scientifically speaking, deterrence is an empirical matter that does not depend on whether the people inside or outside of Singapore believe in it. It is not a matter of opinion.”

(Related, in “Public opinion: barrier to death penalty abolition?”, Sato debunks several myths about the link between the popular view and policy.)

All this points to a somewhat depressing notion: that the Singapore government may be content for people to remain ignorant about the actual deterrent effect. Nevermind all the grand pretences about data and truth in the Smart Nation, about co-creation under a prime minister who wants “we” over “me”, about nurturing a society that protects its most vulnerable. When it comes to the death penalty, these lofty ideals fade under the glare of decades-old conservative dogma, unshakeable in its conviction about what makes Singapore tick.

That’s not to imply that there has been no change. Amendments to the MDA that came into effect in 2013 allowed courts greater discretion in not imposing the death penalty if certain conditions are met, for instance if the trafficker could be shown to have acted purely as a “courier”, and provided substantive assistance to the cops. MHA said that from 2013 to 2022, 82 out of 104 individuals who might have faced the death penalty for trafficking were instead handed life imprisonment (as well as caning, in some cases). Of the remaining 22, 8 were also re-sentenced because of “an abnormality of mind” while for 14 the mandatory death penalty was upheld. Pritam Singh, WP chief, cheered all this in his commentary on the issue. But in our view that’s still 14 too many. The deterrent effect that Singh also subscribes to has no conclusive, empirical basis.

We’ve dealt in this essay primarily with the notions of deterrence and public opinion for those are the drums this government beats. For some, deterrence is crucial in their support of the death penalty. For others, including Jom, even if deterrence is established, there are a slew of other reasons to oppose it, from the base immorality of taking a person’s life to the imperfections of any criminal justice system, which means there’s a risk that an innocent person is executed. In any democracy individual views will differ on these points.

Other important contemporary themes around incarceration and capital punishment include the rights of inmates. Last year the courts ruled that the Attorney-General’s Chambers and the Singapore Prison Service had acted unlawfully when breaching the confidence of letters of 13 people on death row. Separately, there is a shocking lack of racial data on inmates. What would be routine information in other democracies is privileged here—so much so that the government even rebuffed a parliamentary question on it. Unsurprisingly, critics assume the jails (and our death row) must be full of minority men. Our understanding of possible racism in criminal justice is hampered, and possibly exaggerated. In terms of discourse within communities, even as smaller groups like Beyond The Hijab try to promote alternative perspectives on criminal justice, mainstream publications like Berita Harian peddle the government line. In order for democratic discourse to progress, what we all deserve, and which we’re not currently getting, is an honest, diverse public conversation.

Unfortunately, the entire drugs and death penalty debate—a microcosm of larger human rights discussions—has also become poisoned by the spectre of neo-colonialism. With Richard Branson caricatured as the self-righteous White man, and Shanmugam the swashbuckling defender of independent Singaporeans, the debate has come to symbolise a much deeper angst about interference by former colonialists and Western liberals. No doubt, we should assert our sovereignty over such issues. Still, there’s no reason this global city shouldn’t be open to foreign ideas, whether in AI or human rights. Listen, discuss, decide. We undermine our own intellectual diversity by smearing ideas as neo-colonial.

Another reason is that drug mules and addicts (and their respective families) are often framed in opposition to each other. The reductive view is that abolitionists, such as the Transformative Justice Collective (TJC), are concerned only about the former; and the government only the latter. Yet, surely they both want to help both groups. Mules and addicts are vulnerable in their own way, and society must do better to ensure they have richer opportunities that keep them from harm. The path to healthier dialogue, then, necessitates repair of how we understand shared vulnerabilities, and the connectedness of different parties. A genuine discussion about criminal justice should elevate the voices not just of the families who face the trauma of addiction—tragic and serious as it is—but also those who face the trauma of a vulnerable relative turned drug mule (as TJC has admirably and doggedly done). Nobody grows up with the dream of trafficking heroin.

“You put a life sentence at least I can see my brother every now and then,” Nazira Lajim, whose brother Nazeri was executed in 2022, told the BBC in the same podcast. “Nobody can take one’s life except for God.”

Coda

In the first section of this essay, we want to show how the way we speak is codified by our socialisation within a dominant paradigm of propriety. Words like activist and debate have been controlled, their meaning circumscribed by powers both external and within our deepest reaches. Underlined words there conceal our pain, our blinkers, our limits, real and imagined.

We use the death penalty, as if it were just another lever to pull

We want discretion in its application, as if it’s a pimple sticker to paste

We regard it as one of our issues, as if the others, like whether to choose this school or that, are also life and death

We call people junkies, cos it’s easy, cos it’s known, cos it’s cool

We say you’re entitled to your view, as if seeking your thoughts on Lim Kay Siu

We talk about Singapore’s approach, as if plotting our next BTO.

As we share our message, as we speak to you, dear reader, we should never forget the violence embedded in our everyday, our words, our language, that desensitise us, that prevent us from connecting in a way that is more human, that recognises at its core our shared existence. We should never forget that in this discussion, we are the other, pontificating about people whom we must centre, the vulnerable from nether regions we may never know.

This piece is from Jom’s editorial team. We’re grateful to Mai Soto and our other readers.

If you enjoy our work, do get a paid membership today to support independent journalism. It’s the only way we can keep doing this work.

There’s a vigil for death row prisoners at Hong Lim Park from 7-830pm on Monday, September 29th 2025. You can follow the Transformative Justice Collective on Telegram.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.