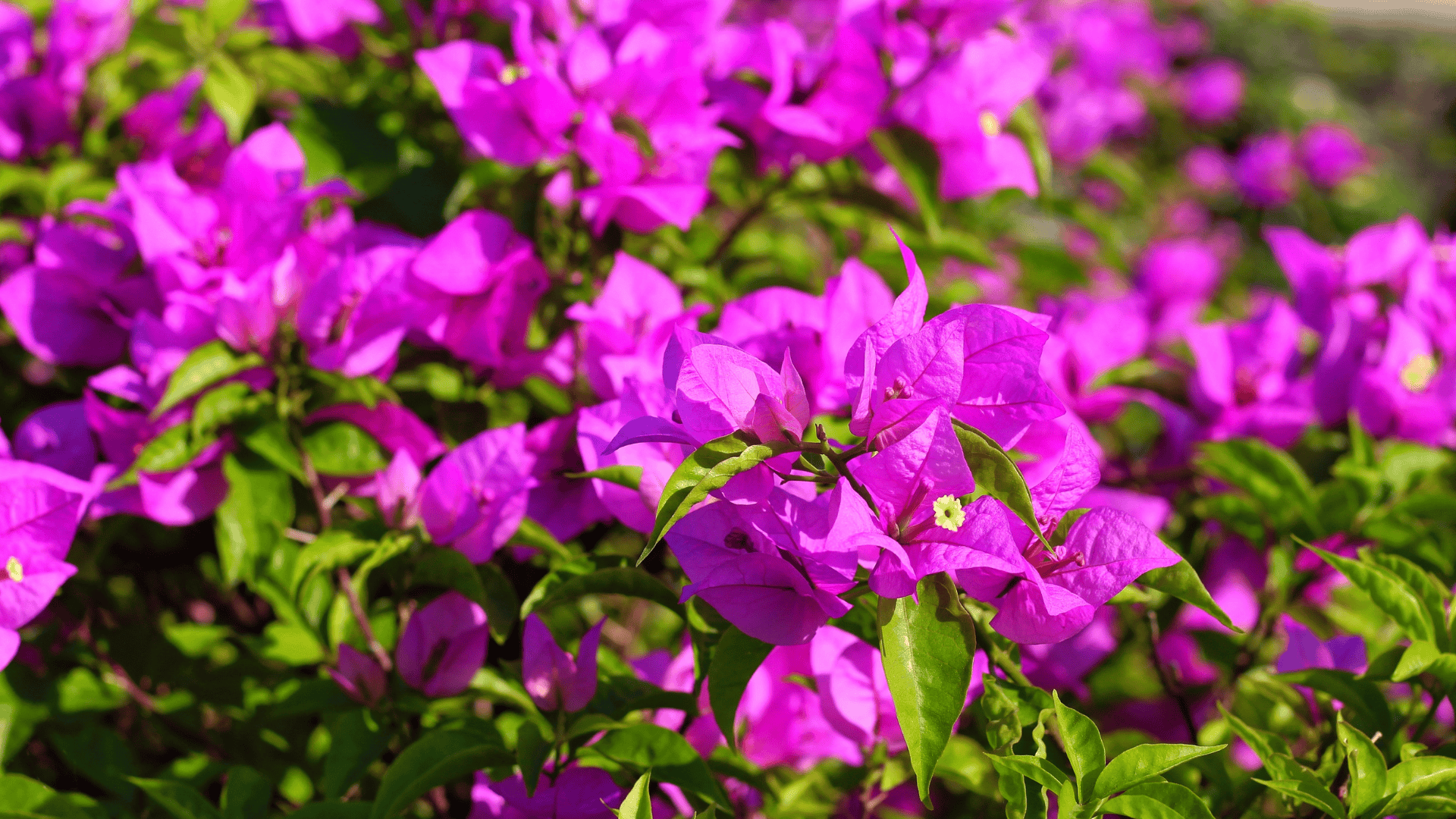

I remember the pink bougainvilleas in concrete planters outside 38 Oxley Road, floral shamans prepping me for time travel. The tall gate and the barbed wire were more awkward than foreboding. And then, the late 1800s structure, so recognisable in our popular imagination. Upon closer examination I felt cheated by the photographs and visual records, by the imagined colonial grandeur of Singapore’s first family. There were signs of age, if not decay. In the flip switches and tiled floors were elements of old Malayan plantation houses I’d visited, but without the care and upkeep that accompanies belonging.

Only Lee Wei Ling lived there at the time, in the only home she’d known, with a debilitating condition and the awareness that competing narratives were being scripted for the day she died. Worse, she probably knew, as we found out last week, that the one she and one brother subscribed to would ultimately, inevitably, “lose”. We sometimes lament Lee Kuan Yew’s final years, spent watching his children squabble over his will, but I wonder what hers felt like. The house, what little I saw, wasn’t so much decrepit as despondent, on borrowed time. Material and spiritual squalor hung in the air of a century-old space. The pink petals dancing on my way out signalled a return.

But to what? Lee Kuan Yew’s material contradictions stayed with me. How is it that the man who nurtured a nation of hyper consumers, people who swap cars, repaint walls, and upgrade smartphones at every opportunity, was himself content with material stasis? Was his greatest trick convincing each of us to become Homo Economicus, to serve the ends of a neoliberal machine that he thought a tropical island must submit itself to—while he, Zen-like, embraced emptiness in myriad forms?

His disciples certainly have no qualms about living the high life, or ignoring his primary dying wish, for his house to be demolished. That he knew it may not happen and that luminaries across the political spectrum didn’t want it to happen is true. But beyond that there is no need to again indulge the bickering between siblings and the granularities of the wills. A meditation on the individual seems more appropriate.

Whether sheathed in Asian Values or some other rhetorical armour, Lee Kuan Yew believed that an individual’s rights must always be subordinate to society’s. One way his SimCity genius implemented that was in widespread land appropriation that yanked thousands from their kampongs and chucked them into towering blocks from which their labour could be better extracted. One wonders if Lee Kuan Yew, as he entered his final years, chuckled at the realisation that his mantras were being turned against him in death. No, Ah Gong, it’s not your land, it’s ours.

But who decides for society, determines what exactly is in the public interest? The natural aristocrats, of course. Lee Kuan Yew was always clear about the problems with direct democracy, and the merits of elite governance and guidance, whether in banning gum or legalising gambling.

And over the past 15 years, his political descendants have elevated this to sublime stagecraft. During representations to Lee Kuan Yew directly and to the public later through the ministerial committee report, our dear leaders repeatedly justified preservation through marvellous narratives about the public interest and presumed public sentiment. Curious, isn’t it, that in the report, and in their messaging to this day, they fail to mention that Singaporeans surveyed have long wanted the house demolished.

Lee Kuan Yew never conducted opinion polls on issues. But now we do, and when the results purport to align with an underlying ideological imperative, such as with the death penalty, we’re suddenly zealous democrats. Else, we’re not. Even as the structure that birthed the PAP has slowly faded, the exercise of the party’s raw power has grown ever more sophisticated.

In the final reckoning, we must confront the melancholy of the Singapore story. Besotted by monuments and gilded cages, incentivised by spiralling property prices, enthralled by humankind’s power to terraform the earth, enervated by a political hegemony paranoid about conceding an inch, and frayed by petty elite rivalries, our soul is laid bare. At 38 Oxley Road, there’ll be no more smoke-fuelled rebellions, no Sunday lunches, no urns and patinated photos, no grandchildren bouncing in the foyer, no children on speaking terms.

We’ll be left not even with a properly preserved house, but a magisterial creation of the hyper efficient, technophilic state, its neatly cut corners and forbidden zones a product of government diktat, computer design, and political wayang, the same irrepressible power dressed for our kumbaya times, masquerading as “we” but still subservient to patrons. Inside there’ll be a story of a man, a party, and a gleaming city-state—but not of the family that crumbled in their making.

I wonder if there’ll still be pink bougainvilleas fluttering outside, ushering us on our descent to creation, and comforting us on our return to paradise. Native to South America, bougainvilleas arrived here a century ago. As Lee Kuan Yew uprooted forests in order to create a “Garden City”, they proliferated across our cemented land. What we think of as flowers are actually modified leaves. We typically ignore the actual white flowers inside. The bougainvillea, it turns out, is a reminder of origins replaced, and illusions lived.

Sudhir Vadaketh is Jom’s editor-in-chief. His first piece on the saga, “The Oxley Road dispute and Singapore’s future”, was published in Foreign Affairs in 2017; and his previous piece, “The battle over Lee Kuan Yew’s last will”, was published as a free e-book in 2022. He hopes this is his last on the subject.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.