Our picks

Politics: Going Noorwhere

For Pritam Singh, Workers’ Party (WP) chief, the name “Noor Deros” may be sounding increasingly like “Raeesah Khan”. During GE2025, Noor, an Islamic preacher, made demands of political parties; said he’d met Malay candidates from the WP (on April 20th); and called on Tampines voters to choose the WP’s Faisal Manap and his team over the one led by Masagos Zulkifli of the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP). On April 26th, the WP repudiated Noor’s comments following a government statement. “There was no indication that this individual would be joining the meeting,” Singh said then.

Last month, with K Shanmugam, home affairs minister, raising the spectre of identity politics, Singh told Parliament that Noor had actually “gate-crashed” the April 20th meeting. But Noor himself then refuted that account in a YouTube video. Faisal had actually delegated organising responsibilities to an ustaz, who had in turn invited Noor. The ustaz informed Faisal via WhatsApp of Noor’s attendance an hour prior to the meeting.

This week, the PAP latched onto this. Indranee Rajah, minister in the prime minister’s office, delivered a ministerial statement, which was followed by Singh’s own pre-planned clarifications on the issue. Parliament was thus treated to another lawyerly debate, this time on the meaning of “gate-crash” and the difference between “know” and “know of”, regarding Faisal’s knowledge of Noor. (Millionaire politicians, once again earning their keep.) True to form, Indranee and the PAP have mercilessly gone after Singh and the WP, part of a decades-long pattern to turn every opposition foible into a question of character and integrity. Ultimately, we’re missing the forest for the trees by obsessing over “gate-crashed” rather than the WP’s rejection of identity politics.

The problem for Singh is not about honesty, for it seems clear that he was all along conveying information to the best of his knowledge. Just like with Raeesahgate, there is an issue here with the WP’s internal communications and cohesion. Why didn’t Faisal inform Singh that Noor had been invited in April? And even if we can pardon lapses in the heat of the GE, why didn’t Faisal inform Singh in the five subsequent months, before Singh uttered “gate-crashed” in Parliament? Faisal showed Singh the WhatsApp message, we now know, about a week later. The WP’s base won’t be too bothered by all this, but some of the voters Singh seeks to win over will wonder.

Society: Baked? More like left out to dry

For some 80 employees of Twelve Cupcakes, the evening of October 29th marked not just the end of a work day, but the abrupt loss of their livelihoods. There was no warning; not even a whisper of trouble. According to CNA, liquidators entered the bakery chain’s office at 5pm while some staff were “still at their desks”. Others learned of the company’s provisional liquidation and their contract termination via WhatsApp at 8pm. To make matters worse, the blow came just two days before payday, leaving former executives, managers and rank-and-file workers wondering if they’d ever see their final paychecks. So far, it’s not looking good. “No one is answering our call…They are all ignoring us,” one former employee told The Business Times. “We don’t deserve this,” said another.

Indeed. Yet the writing, perhaps, was already on the wall. Once a darling of Singapore’s homegrown F&B scene, Twelve Cupcakes has been bleeding in recent years, recording a net loss of S$1.23m in the latest financial year ended March 31st. Founded in 2011, the chain’s reputation has been marred by labour violations. In 2020, its celebrity co-founders, Daniel Ong and Jaime Teo, were fined S$65,000 each for underpaying eight foreign employees between 2013 and 2016. The following year, its new owners, India-based Dhunseri Group (which acquired the company in 2016) were fined S$119,500 for similar offences involving seven non-local staff.

The Food, Drinks and Allied Workers Union (FDAWU), under which the company is unionised, was blindsided too. It condemned the surprise closure as “unacceptable”, “unfair” and “irresponsible”, criticising the “lack of prior consultation and advance notice”. FDAWU, which is affiliated to the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC), is now helping affected staff to file salary-related claims and find new jobs. The stakes are especially high for work pass-holders like Parmjeet Sharma, his family’s sole breadwinner, who needs to find a new job in one month, or leave Singapore.

Twelve Cupcakes’ sudden closure has sparked renewed scrutiny of the ability of Singapore’s labour laws to protect employees when firms dissolve overnight. Some netizens called for legislation mandating that workers be paid in full or part before the “highest debtor”. Time, maybe, to also consider something like Japan’s System for Reimbursement of Unpaid Wages scheme and France’s AGS wage guarantee scheme, which compensate unpaid wages through state-backed funds. Meanwhile, others questioned the power of unions; asking “what’s the point?” since NTUC and its affiliates can’t penalise irresponsible businesses anyway.

In the end, it’s not just cupcakes that have crumbled, but the trust between employers and workers. As Singapore nurtures an entrepreneurial culture, we might sooner value how responsibly a business fails, as much as how quickly it rises.

Society: Got nothing better to do

“Stay away from crime”, school discipline masters would warn during end-of-year speeches. They’d hold canes and present slides with statistics of juvenile delinquency. Different generation, similar problems. Our worries have shifted from teenagers being “runners” for ah longs, to money mules for scam artists.

In October, parents of secondary schools and junior college students received a government advisory with “tips” to prevent their wards from committing or being a victim of shop theft; cheating via involvement as money mules; voyeuristic, non-consensual filming; rioting; and being part of unlicensed moneylending harassment. It also had a dedicated page on scams and how students can be safeguarded against them, another page on drug and inhalant abuse coupled with cautionary “real life stories”.

The top two offences committed by youths aged between 10 to 21 in 2023 were shop theft and cheating. An interim report by the Singapore police found that 271 youths aged 10 to 19 were arrested for shoplifting in the first-half of 2025 compared to 192 in the same period last year. Another police study found that in scam cases reported between 2020 and 2022, 45 percent of the mules were 25 years old and under. Advisories are regularly circulated during school holidays, assuming that students are more likely to commit crimes during the holiday season—too much free time, too little adult supervision.

Experts suggest shoplifting incidents are impulsive attempts by teens, whose prefrontal cortices aren’t fully developed, to puncture life’s monotony with new thrilling experiences. Sometimes, they are peer pressured for “clout” to fit in social circles. Youths involved in cheating cases are lured by the possibility of “quick cash” and rarely aware that they’re cogs in larger, organised crime. Moreover, for teenagers—who are typically not financially independent—“fun” has been shaped by consumerist culture and social media. From unboxing Pop Mart blind boxes, eating Yochi yoghurt to buying trendy sneakers, teenagers’ leisure life is ironically centred around purchasing power. Online, their social media feeds teem with male Gen Z hustlers and local influencers posting lavish lifestyles, which reinforce the idea that happiness and community can be bought. Or stolen.

It’s no surprise some end up chasing high-paying holiday “jobs” just to keep up. The rise in youth shoplifting and scam involvement reflects this shifting landscape of teenagehood—one where leisure feels transactional and joy, a commodity. Perhaps the teens need more than just advisories, but ways to be lured away from the screens to “touch grass”.

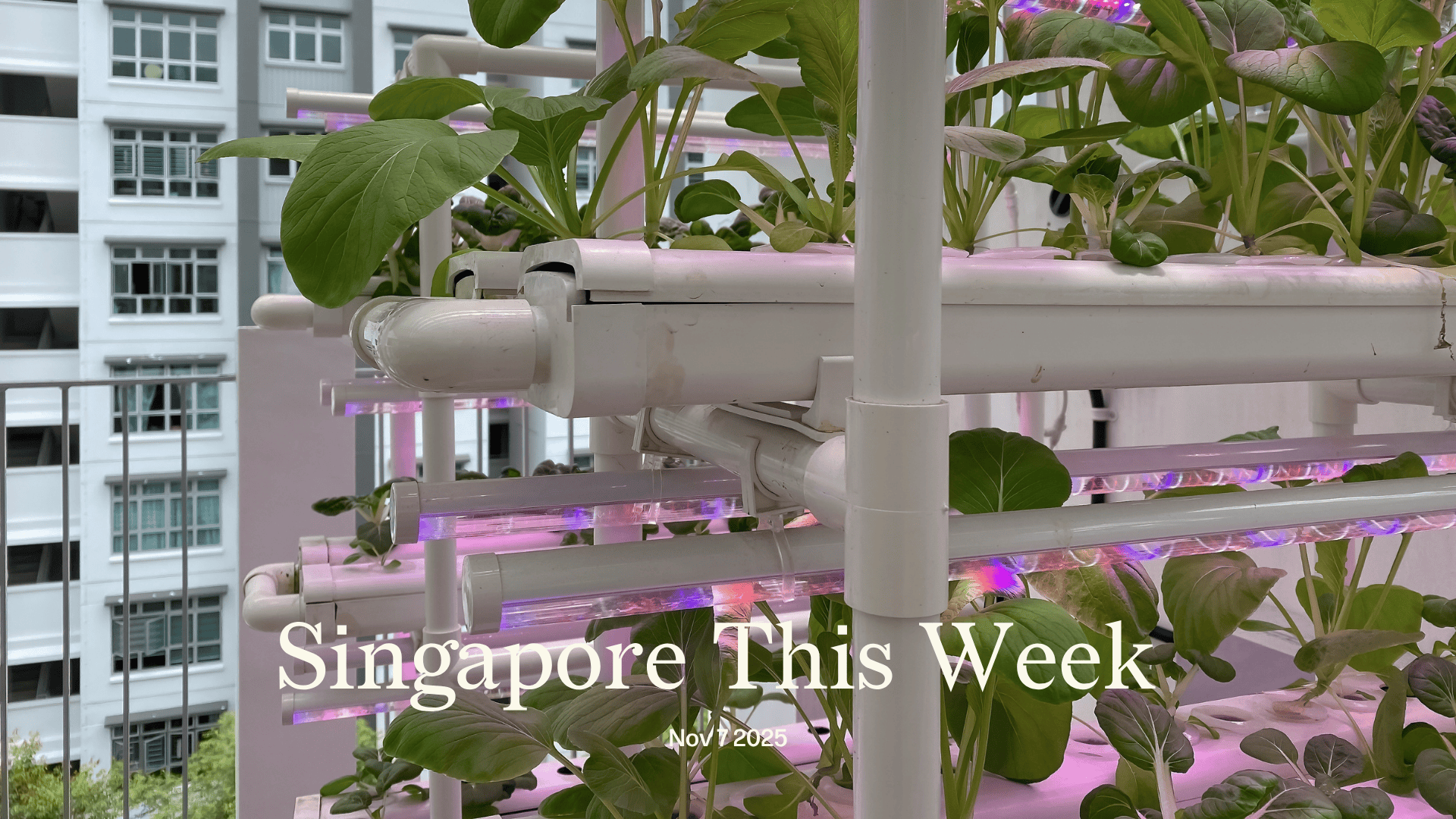

Society: The grim reaper comes for “30 by 30”

In 2008, bad weather and rising fuel prices sent imported raw food prices in Singapore soaring by 55 percent; rice and grain by over 31 percent. By 2050, climate change could reduce global crop yields by a quarter. Jolted by the past and bracing for the future, Singapore–dependent on almost every single UN member nation for more than 90 percent of its food–launched the “30 by 30” programme in 2019: local produce would sate 30 percent of our nutritional needs by 2030. Six years later, it’s dead. What went wrong?

The plan hinged on hi-tech sea-based farms for fish and indoor hydroponics-based vertical farms for vegetables; traditional farming hasn’t been the norm here since the government cleared over 15,000 hectares of tapioca, sweet potato and other crops for housing, malls, and factories in the 1970s and 1980s. Economic prosperity simply wasn’t simpatico with food self-sufficiency on a tiny island with a ballooning population. Covid-19 struck within a year of the programme’s launch, gumming up supply pipelines and jacking up labour costs, hardly ideal for a minnow industry. (Even as the isolation from global supply chains increased conviction about the need for greater self-sufficiency.) But there were deeper issues too.

Singapore’s coastal waters are already hostile to some of the farmed fish species, and are worsened by contaminants from the behemoths that call at its port. Indoor farms are more space efficient than traditional ones but need uninterrupted artificial light that drives up energy costs. Add in the other hi-tech inputs needed to grow seafood and vegetables at scale, and local produce could never compete with imports. Demand never took off.

Some critics say that in a country where food and land have long been divorced, the government could have done more to tell Singaporeans why homegrown produce matters. “Five years too late,” said Wong Jing Kai, a local fish farm owner, when the message finally made its way to schools in 2024. Others argue that financial support for agri startups didn’t extend beyond the initial grants, leaving them to duke it out against leaders in a market where cost of living has heightened price sensitivity. Veera Sekaran, National University of Singapore professor and founder of VertiVegies, a vertical farm, told Eco-Business last year that imports had to be curbed and subsidies raised for local produce to flourish. Whisper it, but…protectionism. “If you say that they have to compete with market forces, and then when they don’t do well, that is their problem…then what is food security?”

Eggs now meet a third of national demand but local veggies and seafood have lower market share today than when “30 by 30” was launched in 2019. Firms once hyped up as ushering in a new era of food security for Singapore have shuttered, relocated, or shrunk operations. Singapore has pushed its food security goals to 2035, and shifted the goalposts too, with focus now on fibre and protein–current darlings of the “dietarati”. May the real harvest of 30 by 30 be the lessons it provides for the future.

History Weekly by Faris Joraimi

In all likelihood, few can name the largest painting in the National Museum’s Singapore History Gallery. Unsurprisingly, it’s a portrait of a colonial ruler: Frank Swettenham, resident-general of the Federated Malay States (1896-1901) and governor of the Straits Settlements (1901-04). He’s depicted in an all-white uniform, a medal from Queen Victoria, and a sabre, leaning over a gilded chair with a map and globe showing the Malay Peninsula. An explorer’s pith helmet rests to the side. These are signs of power, expressing the capacity to document geography and dominate it. But I couldn’t ignore one prominent object in this scene: an exquisite Malay brocade, or songket, draped over the chair. Supposedly collected by Swettenham, it’s the work of an anonymous artist (almost certainly a woman, as all songket-weavers tended to be), placed here as a trophy to narrate his career. There’s a gendered element to Swettenham’s figure, in masculine posture and stiff clothes, arm over the supple fabric folding over itself. A sharp keris would upset the message. Yet the songket glints, communicating its presence there, the gold weft catching light in varied shades. It doesn’t subvert the visual statement of imperial authority overall, but it certainly does draw your eyes—at least momentarily—away from the stark figure of the coloniser himself.

In great-man history, Swettenham’s place is secure. He masterminded the precursor to Malaysia’s present-day federal system and brought “civilisation” to Malaya—oh yes, roads, railways, plantations, order, justice, and all that. Swettenham also wrote for the public. His books, including Malay Sketches (1895) and The Real Malay (1899) speak with confident and witty racism, on a reality both intimately observed and invented. So it was fitting, some thought, that he should be painted by the best portraitist of the age. In 1904, the year Swettenham retired, the Straits Settlements Association in London commissioned none other than John Singer Sargent to paint the governor. He was no ordinary contractor. Sargent the American enjoyed international fame, and was friends with the great Impressionist, Claude Monet. Among Sargent’s works celebrated in Western art history, his Portrait of Madame X is most renowned, the “Mona Lisa of the American art collection” at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. We can’t easily claim his Swettenham picture as part of Singaporean art history—whatever that means—but the songket, by a South-east Asian artist, completes it.

Arts: All fired up about clay

“It’s very hard work to do pottery,” Iskandar Jalil declared. “You make 10 pots and they are very beautiful, but they are ugly. I look for the unusual ones, the ones made by accident.” The 85-year-old master potter, undeterred by prostate cancer and cataract operations, still throws and sculpts his beloved clay, driven by an ethos of imperfection and repair. You’ll get to see some of the Cultural Medallion winner’s prized works—the pieces he can’t bear to part with, and that occupy pride of place in a private rooftop gallery—at the Singapore Clay Festival, which runs till Sunday. These include a pair of perfectly imperfect small pots made earlier this year, both adorned with twigs, a signature embellishment of his, and weathered naturally in a canal by St Patrick’s School. The respected ceramist will join over 200 other clay makers, both experts and enthusiasts, in a lineup of exhibitions, workshops, demonstrations, masterclasses and pottery throwdowns at the biennial festival.

Pottery is still riding a post-pandemic wave, alongside a swell of other hobbies that honour the haptic and savour the community spirit, from collecting vinyls to crafting zines. Singaporeans, set on surviving the isolation of Covid-19 “circuit breakers” and “heightened alerts”, flocked to pottery classes en masse, forcing studios to wedge bigger safe-distancing gaps between students. One of those Singaporeans was Kevin Chua, who took his passion for pottery out of the studio and into a Bedok void deck. His wife gave him a pottery package for his birthday, which is when he made his first piece, a small trinket dish. He found the experience profoundly therapeutic. Over 80 lessons later, he started a studio in his own home, but had to push pause on this endeavour after his mother died two years ago. “I was so emotionally tied to the house. Every time I looked at the space and realised she wasn’t there anymore, I knew I couldn’t go on making pottery at home,” Chua told CNA.

The day he sold his flat, a Bedok South void deck kiosk came up for bidding. Chua applied for it—and got it. Today, Studio SF serves both the neighbourhood’s residents as well as the eldercare centres that surround it. These senior students were, initially, often terrified of imperfection. “They’d say, ‘I’m scared it will break, mine looks so ugly.’” Fast-forward two hours, and the same aunties and uncles would go, “‘Oh wow, it actually looks so nice!’” The mistakes, the accidents, the cracks and smudges: these are all part of a pottery practice. Take “Tall Vase”, a 1976 piece by Iskandar scarred by his left arm, a mark he left behind when rescuing the rogue pot from flying off the wheel. “The distorted is beautiful,” Iskandar once told ST. “We must pass this on to the young so that they will respect old people, people who are handicapped, birds with one leg hopping around.”

Arts: Bumper stickers

You’re at your favourite cafe downing the final dregs of your coffee. Your lunch break is almost over, and you’re trying to relish those final few minutes with buddies who’ve rearranged their schedules to spend a meal with you. As you head to the cashier for the bill, your gaze snags on a stack of stickers arranged, enticingly, in front of the register. They’re cutesy renditions of exactly what you had for lunch: a grilled cheese with mushrooms and a side of tomato soup, each anthropomorphised with Mona Lisa smiles and dots for eyes. Uh, how much are these?! You buy them, and find out they’ve been designed and printed by a kid barely into their teens. These are the Gen Alpha and Gen Z sticker sensations, popping up at art markets and coffee shops all across Singapore, and making a killing from their character creations.

Young artists and designers, often self-taught and wrangling demanding day jobs, have been creating popular characters and leveraging pop-ups and art markets such as Public Garden to scratch their creative itches. There’s “Avocagoh”, a derpy and endearing portmanteau of 25-year-old illustrator Sarah Goh’s last name and the fruit with a millennial association. There’s “Robert the Corporate Frog”, the burnt-out amphibian and brainchild of Arissa Rashid, also 25, who comes in both three-dimensional plushie and two-dimensional sticker form. Dylan Chia, 21, is the brains behind DCHTOONS, where he’s leaned into Singapore’s culinary culture with punny sticker productions: “look ondeh bright side”, goes a grinning bulb of ondeh-ondeh; “kopi-ng with stress”, goes a teary-eyed bag of strong coffee.

If they play their cards right, these emerging entrepreneurs can sometimes make thousands from a blend of online savviness and offline canniness. They’ve had to learn how to connect with potential fans, and when it might be wiser to consign products to stockists across Singapore. “Most artists don’t put themselves out on social media, so doing booths is a great way to get started,” Chia, a taekwondo athlete and graphic designer, told ST. “You get to make new friends, and finding community is very important. Things can get very lonely. Having a community makes the whole journey enjoyable.”

Faris Joraimi, Abhishek Mehrotra, Sakinah Safiee, Corrie Tan, Tsen-Waye Tay, and Sudhir Vadaketh wrote this week’s edition.

Letters in response to any blurb can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.