Dear reader,

Quick announcement. There are now over 1,500 of you subscribed to this newsletter. Hooray! Thanks for following Jom. We want to grow the community. So if you enjoy this newsletter, please forward it to your like-minded friends and fam! OK, back to ‘jom’...

Though we love our name, people needed some convincing.

One objection was around using a Malay name for an English-language magazine. Would it work? The other was around cultural appropriation. Would it be right for a company with two Chinese and one Indian as co-founders to be using a Malay name for their brand?

I’ll eventually get to these, including why we were a bit more concerned with the first than the second, but first, let’s meet the word ‘jom’.

Jom is Malay for ‘let’s’. It is commonly used by friends as a single-word call to action. ‘Jom, let’s go!’ It has many other everyday uses, such as ‘Jom makan’, ‘Let’s eat.’

Jom rhymes with 'roam', though it is sometimes pronounced 'zhom' by Chinese Malayans.

A common word in Malaysia, jom has in recent decades slowly entered the Malay Singaporean vernacular.

I’ve always loved the word 'jom'. Loved seeing it, loved hearing it, loved saying it. It has a snappy, fun, feel-goodiness to it, somehow both comforting and energetic.

Jom is, to some, an example of onomatopoeia, which is the creation of words, such as 'hiccup', 'sizzle', 'oink' and 'roar', that phonetically sound like what they intend to represent. Every time I say ‘jom’ I feel like turning my head to one side and nodding to a buddy. Let’s do this.

No matter how it is used, jom connotes a sense of camaraderie and togetherness, of a shared sense of purpose. How did we find it?

Finding Jom

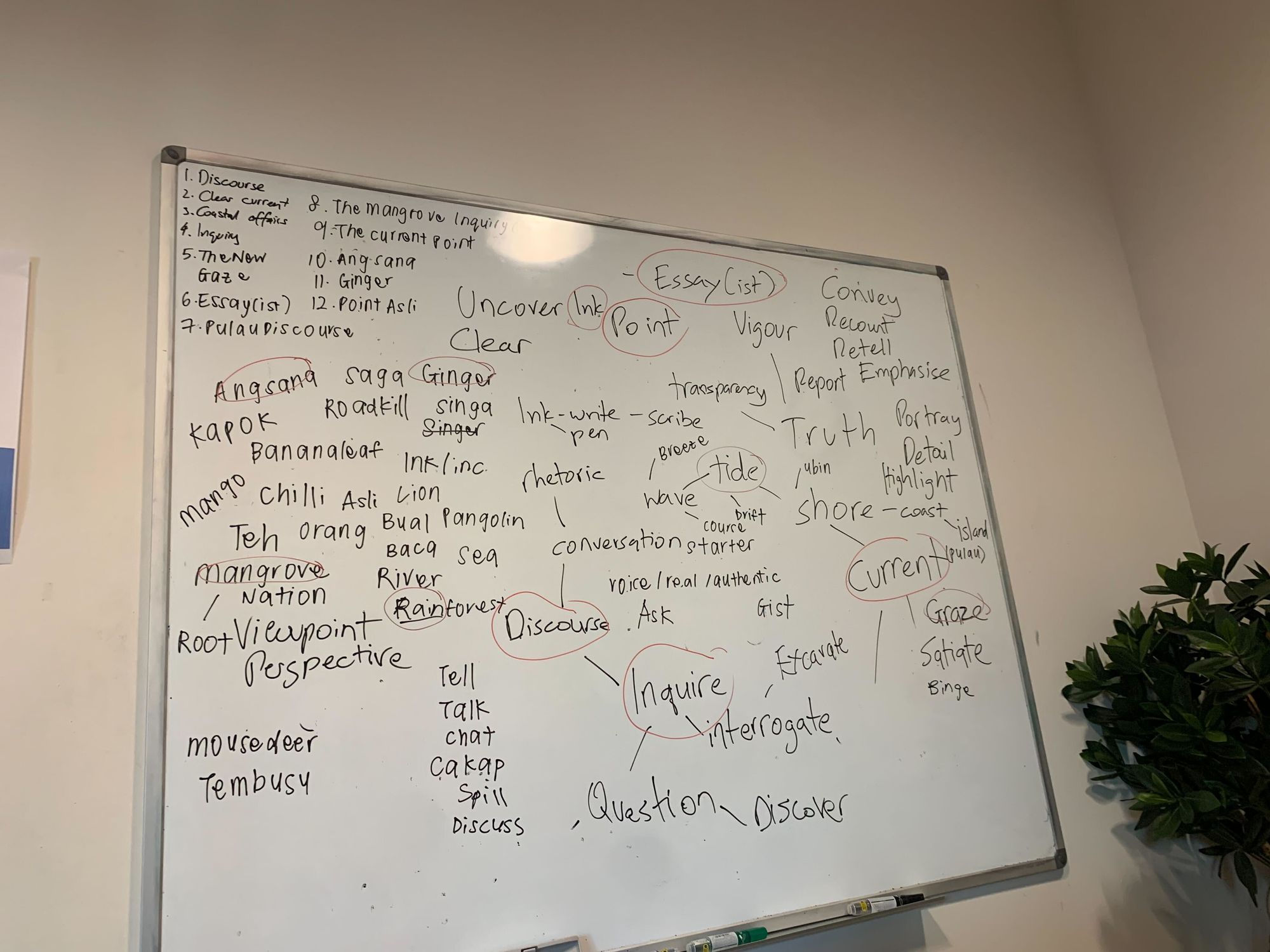

In January this year, weeks before we started work proper, I spent six hours over two days with the three other members of Jom’s core team: Charmaine Poh and Tsen-Waye Tay, my co-founders, and Jean Hew, our head of research and first employee.

Brainstorming names—whiteboard, laptops, lots of caffeine—was one of the first things we did. We hardly knew each other. It felt like we were feeling our way to healthy communication as much as a magazine name.

I don’t know why but I was quite taken by the idea of either coming up with our own name, such as Google, creating a suitable portmanteau, such as Microsoft or Netflix, or stealing a memorable name from literature. For example, Palantir, a big-data analytics company, is named after Saruman’s crystal ball in Lord of The Rings.

It was not to be. Our shortlist included two English names (Charcoal and The Currents) and three Malay ones (Bumi, Halia and Jom). We tested them with our focus group of some 25 people.

For Charcoal and The Currents, there was only moderate enthusiasm for them, and for the latter there would have been brand confusion and search engine optimisation (SEO) challenges, which is a common problem with many English names.

And bumi? It was a polarising choice with a clear generational divide. It totally triggered some of my kakis—the older people—who immediately think of bumiputera, which means ‘sons of the land’ in Malay. For them bumi has connotations of Malaysia’s unjust bumiputera policy, of racism.

By contrast, many younger ones think of Bumi, a character from “Avatar: the Last Airbender”. For them the connotations are more around the word's actual etymology: earth, green, planet.

I like bumi for somewhat similar reasons. Bumi Manusia, this earth of mankind, is one of my favourite books by one of my favourite writers, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, whom I was lucky enough to meet as an undergraduate, before he passed.

In any case, there was more than enough annoyance to push bumi off our list.

Our final shortlist had just three Malay names: Jom, Halia and Selat. Selat, which means ‘strait(s)’ and is an old name for Singapore, was a late entry after the focus group session. Halia means ‘ginger’, a plant that is native to South-east Asia, from where it spread across the world. We like all three for different reasons.

Halia was ruled out first, partly because in Singapore the name makes many think of a restaurant in the Botanic Gardens. And we finally settled on Jom partly because of the energy. Onomatopoeia. Selat was somehow a bit too languid, even if some believed that it was more in keeping with our ethos of slow journalism.

Jom, ‘let’s’, signifies our collaborative, empathic approach to journalism. Its starting point is a harmonious relationship between readers, writers, interviewees, communities, the planet, and other stakeholders—a harmony that thrives on the contestation of ideas. We’ll discuss Jom’s values in greater depth on the About us page on our website, which should be launching in the coming weeks.

Does it make sense to have a Malay name for an English-language magazine?

Charmaine, Jean, Waye and I have always been comfortable with a Malay name. Singapore is in the middle of the Malay world. Malay is our collective language, spoken by many of our non-Malay ancestors, but few non-Malays today. It is a shame, in our view, that such a beautiful language has withered away from our national consciousness.

“The Malay language in Singapore is like a cultural antiquity that we dust off and parade shamelessly whenever we want to show how diverse we are, how tolerant we are, how local we are,” I had written in a Mothership commentary on Singapore’s 49th birthday, in 2014. “The only times the vast majority of Singaporeans will ever use Malay is when it creeps into Singlish, our delightful creole…And, of course, when we sing 'Majulah Singapura'.”

All of us at Jom believe that conversational Malay should be a requirement in Singaporean schools. In a way, then, there is ambition and aspiration in our choice of a Malay name for this English-language publication about Singapore. Through our actions we are building the Singapore we want to see. We may have been a bit more concerned about using a complex, unpronounceable Malay word. But 'jom', well, is easy and catchy enough.

Finally, the name positions us quite well for expansion across the region, if we’re ever in the position.

Is it cultural appropriation for a non-Malay team to use a Malay word for their brand?

A couple of people asked us this question, mostly I suspect because they wanted our new outfit to steer clear of all potential cultural landmines.

It annoyed me slightly, at a personal level, mostly because culturally I feel very “Malayan”, whatever that nebulous identity means. My paternal ancestors migrated to Malaya from Kerala in the 1920s. Today most of their 200-odd descendants live in Malaysia. My rellies and I speak more Malay than Malayalam. A question like that makes me feel labelled, boxed in, curtailed in my freedoms by my ethnicity.

All cultures emerge and evolve through a process of hybridisation and creolisation. I agree with Kwame Anthony Appiah’s critique of cultural appropriation as a concept, while sharing his belief that cultural offence and exploitation are real problems. There may be times when “cultural appropriation” is misused to actually denote offence and exploitation.

So we must tread carefully. Jom as a name? That’s just a celebration of a shared language.

What is an example of cultural offence? Sometimes it’s clear, as in the case of brownface. Other times, less so. Imagine, for the sake of discussion, if Jom had used an illustration of a kampong for our company logo. Is that offensive? Many would say 'yes', given Singaporean society’s depiction of the kampong as a backwater, and the stereotyping of Malays as underdeveloped. (Even if we don’t say it’s a Malay kampong, there is a risk some might interpret it as such.)

Yet I can see an ecological argument in the other direction. Is the village morally inferior? As much as we aspire to speak Malay, one might argue that many of us aspire to a Singapore that is less concrete, greener and—dare I say it—more like a kampong.

Anyhow in my view, and please disagree, the hypothetical use of a kampong for Jom’s logo would qualify as a cultural offence.

What is an example of cultural exploitation? Imagine if Jom stole a photograph from a Malay couple’s wedding shoot and blew it up into a life-sized decorative platform that we then used at our Jom launch party, this coming December. That’s exploitation.

A similar thing, tragically, happened to Sarah Bagharib and Razif Abdullah last year in Singapore.

The point of all this, simply, is to say that while “cultural appropriation” is a loaded, slightly problematic concept, in a multicultural society with gross inequalities and power gradients at play, we should always be on our guard against cultural offence and exploitation.

So, to those voices who a few months ago asked whether it might be appropriation for Charmaine, Waye and I to pick jom, thank you.

Best wishes,

Sudhir Vadaketh

Editor-in-chief, Jom

Some further reading

The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity by Kwame Anthony Appiah, a British philosopher, is a wonderful and accessible exploration of knotty concepts around culture and identity. I think it should be required reading for anybody living in a multicultural society. It will resonate particularly with anybody who identifies as multiracial or “third culture”.

Remember to read the translation of Majulah Singapura by Alfian Sa’at, Singaporean playwright, so that you know what the words mean when you hear them tomorrow. For many of us, the journey to conversational Malay might begin there.

If you've enjoyed our newsletter, please scroll to the bottom of this page to sign up to receive them direct in your inbox.