For subscribers only

Subscribe now to read this post and also gain access to Jom’s full library of content.

Subscribe now Already have a paid account? Sign in

Through the process of making onde-onde, Berlin-based writer Law Zi-Ting meditates on what it means to embrace ambiguity and unpredictability in a world that operates on data and strict binaries. “Steam sweet potato until tender.”

Subscribe now to read this post and also gain access to Jom’s full library of content.

Subscribe now Already have a paid account? Sign in

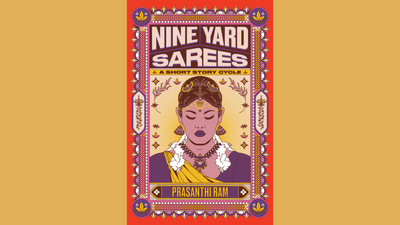

Through its female protagonists, this short story cycle lays bare the complexities, confusions and conflicts that are central to the Indian diasporic experience in Singapore, says our reviewer.

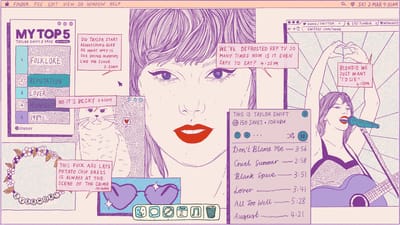

A Swiftie reflects on the extremes of adolescence as seen through fandom and internet culture, remembering how Taylor Swift’s music punctuated key technological changes in her life, and offered her space for self-reflection and growth.

The author reflects on his journey with Javanese gamelan music, one that connects practitioners and ensembles scattered across the world, and conjures musical seascapes that reflect the diverse communities encountered along the way.

On the eve of Vesak Day, Marissa Lee reflects on how she stumbled into Buddhist Singapore during the pandemic, and what she’s since learned about meditation.

Honesty. Fearlessness. Independence. Balance. Quality of writing. Care and love of the writers. Depth of research. Humour. Jom’s recently concluded reader survey, our first ever, was gratifying partly because of the responses to the question, “What do you like most about Jom and why?” We’re still new, we’...

Please click on the link sent to your e-mail to login to your account.