For subscribers only

Subscribe now to read this post and also gain access to Jom’s full library of content.

Subscribe now Already have a paid account? Sign in

KC Chew has lived a life of risk, rebellion and rebirth. Detained without trial in 1987 for being a "Marxist conspirator", the connector of people has tried to straddle the line between the establishment and the outside. Has he succeeded?

Subscribe now to read this post and also gain access to Jom’s full library of content.

Subscribe now Already have a paid account? Sign in

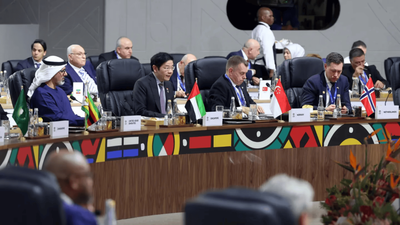

International waters grow more treacherous, and voices at home clamour for greater say in foreign policy direction. What course will Singapore strike?

The recent Forward SG exercise hints at the radical promise of deliberative democracy in Singapore. Can we live up to it?

A shift to an open-by-default data governance structure would foster the more participatory society the PAP claims to want.

Lawrence Wong’s new cabinet reflects tinkering to distribute power and foster teamwork, his desire to reward performance, and possible strategising ahead of the next election.

Lawrence Wong and the PAP were the big victors at GE2025, though the WP and society at large can take consolation from the results.

Please click on the link sent to your e-mail to login to your account.