Arts: தலைவர், Thalaivar, ‘Leader’

A local firm gave its Tamil workers a paid holiday, plus a S$30 F&B allowance, to watch the first day, first show of “Coolie”. Another, a mini-mart operator, suspended morning operations. WhatsApp groups buzzed ahead of ticket sales. Cineplex chain Cathay has opened up more than 50 shows for Saturday, August 16th, hoping perhaps that “Coolie” will revive its wilting fortunes. To embrace the task of describing the hero’s fandom is to embrace hyperbole itself.

So, here goes: producers sign on with him without so much as glancing at the script. Directors fall over themselves to thank him for the privilege. Distributors and theatres know, with the same certitude as the sun rising, that a single one of his films will put asses in millions of seats. Rumour has it that he commanded S$30m for “Coolie”. Co-actors say the honour of sharing the screen with him is honorarium enough. The mere thought of being at the receiving end of one of his reality-bending punches sends frissons through extras fortunate enough to appear in a scene with him.

His fans. From California to Australia, Germany to Japan; Tamil migrants fresh off the boat and those long-settled in foreign lands; white-collar and blue-collar; man, woman, everyone in between and beyond. In restaurants and pubs; living rooms and hotel lobbies; on park benches and grass patches they exchange trivia, belt out his songs, and trade punchlines from one of the 170-odd films he has graced in a 50-year career.

In homes, his photograph sits beside religious idols; outdoors, 10-storey cardboard cutouts of his likeness are bathed in milk, an honour reserved for the divine. Online, videos of fans erupting in theatres when he makes his first on-screen appearance garner hundreds of thousands of views, as do clips of those trying to imitate inimitability itself—a cigarette flicked into the air, somersaulting before perching perfectly between the lips; pens in either hand furiously signing documents, in unison. He has inspired a meme industry that puts Chuck Norris to shame. He killed the Dead Sea. He uses hot sauce for eye drops. He can divide by zero.

Academics publish papers on the aura of his finger-pointing gestures, sprinkling their titles with terms like “self-reflexivity” and “paratext”. For outsiders, he is a curiosity; for insiders, a demigod, an ideal human and the phenomenon of the past half-century. He is Shivaji Rao Gaekwad; screen name, Rajinikanth. His fans call him Thalaivar. Leader, in Tamil, but really, a term that folds awe, love, respect, and devotion into one. No words can quite hold the cultural weight he carries. The only way is to witness it, not just with the eyes but with every one of the senses.

Arts: Seeing sounds at The Listening Biennial

Morning “uwu” of koel birds. Drilling from a construction site. Honks, beeps, and ring-rings at the neighbourhood street. The crying of a child. We listen to these sounds, though often within the constraints of our individual selves, and socialised ways of being and comprehending the world. But what if there is another way of listening, one that can emancipate us from our egos, and connect us to other human and more-than-human beings in ways that offer deeper insights into life?

This is the conceit of the concept of third listening, “imagined as a listening done together, relying on each other to help in acknowledging and overcoming certain listening habits or when listening may fall short,” writes Brandon LaBelle, an American artist and sound theorist. He builds on the concept of “the third” developed by psycho-analyst Jessica Benjamin, who challenged the traditional notion of “doer and done-to” with the idea of “two like-minds” equally shaping the experience of analysis. “Third listening seeks to enhance and extend relationality as a particular kind of commitment, finding in thirdness a path by which to give greater traction to listening’s transformative power.”

The act of listening is recast as influential to restorative processes and repair, to being attuned to one’s own body and behaviour, to challenging systems of abuse, to working at greater social inclusion, to appreciating interspecies connection in service of a thriving ecology and greater planetary understanding. Perhaps this cacophony of academic theorising is difficult to grasp on a page. Thankfully, aural immersion will soon be here. In conjunction with the Singapore Night Festival, The Listening Biennial will be hosted in Singapore for the first time from August 22nd to September 28th across Waterloo Street. With LaBelle as artistic director, the Singapore edition is co-programmed by artist Alecia Neo and Ethos Books publisher Ng Kah Gay, and emphasises third listening centred around deep empathy with the plurality of lifeforms.

The exhibition features sound-based installations by local artists and collectives like Superlative Futures. It will showcase three artworks and a guided experience that “prompt more careful attunement to the weathering world”, for instance through soundscapes of monsoonal downpours and the ebb and flow of oceanic waves. Rachel S Y Chen’s “My Tiny Space” steers us closer to each other, physically. Chen’s installation, features the Magical Musical Mat (MMM): music plays when two people on the mat make skin-to-skin contact with each other and shifts dynamically based on their touch-based gestures. By intersecting sound with touch, a new listening practice emerges where communication transcends dialogue.

For a city which prides itself on constant renewal, it’s perhaps time to imagine “progress” as something not only to be seen, but also listened to. From the high-pitched whines of heavy machinery to the thudding of a soccer ball against our void deck walls, the sounds we embrace and exclude are indicative of the ways we define success. Let’s listen, together, in new ways.

International: Malay bonhomie at Marina Bay

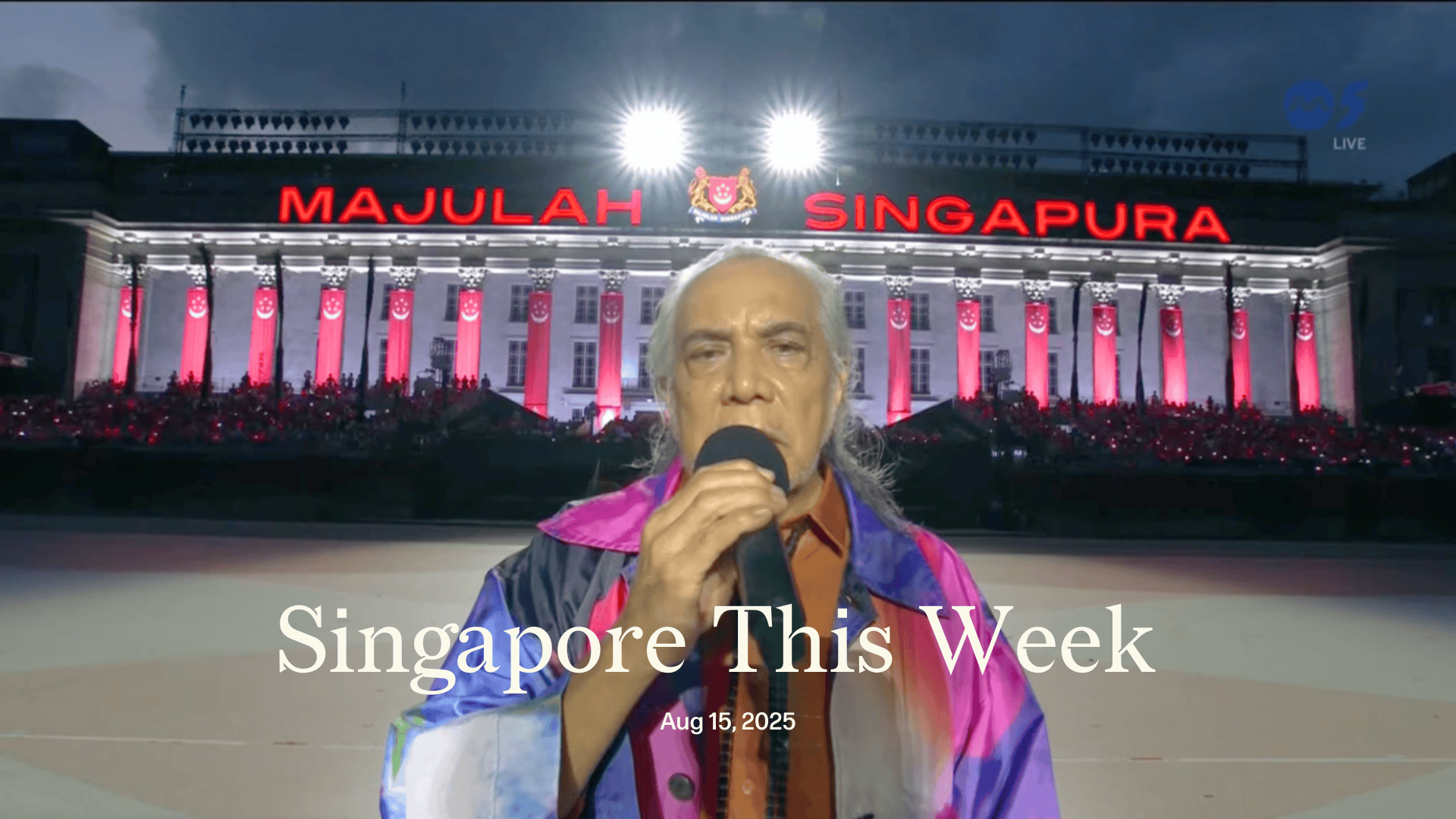

For the first time since 2019, foreign leaders attended our National Day Parade: Zahid Hamidi, Malaysia’s deputy prime minister; Tunku Ismail, regent of Johor; Prabowo Subianto, Indonesia’s president; and Hassanal Bolkiah, Brunei’s sultan. Our neighbours may have enjoyed the widespread Malay Singaporean representation: Firdaus Ghazali, lieutenant colonel, was parade commander; Muhammad Iskandar, lieutenant colonel, led the F-15 flypast; Ramli Sarip, the 72-year-old “Papa Rock”, delivered a spoken-word rendition of “Majulah Singapura”; and many others were recognised, such as Nuryanee Anisah, founder of Commenhers, which has helped over 70 housewives earn an income by upcycling fabric waste.

The military appointees were particularly significant. The Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) was founded and built-up, with the help of the Israel Defense Forces, largely because Lee Kuan Yew was paranoid about the existential threats from our neighbours. In 1960, he worried that independence would lead to a situation where “...about four to five million Chinese will be living cheek by jowl in an independent Sin-chia-po in the midst of 100 million hostile Malays and Indonesians.” He also questioned the allegiance of Singapore’s own Malay Muslims, so barred them (and other Muslims) from many sensitive areas of the SAF. This fed distrust of Malays in society.

Although the policy has been slowly relaxed over the decades, the misconception persisted. In 1999, BJ Habibie, Indonesian president, was quizzed by Taiwanese media about discrimination against ethnic Chinese in Indonesia. He responded with whataboutism. “The situation in Singapore is worse. In Singapore, if you are a Malay, you can never become a military officer. They are the real racists, not here.” Habibie, who also coined “little red dot”, which we now wear as a badge of pride, was plain wrong. Shortly after his statement—or because of?—the SAF’s Officer Cadet School awarded its sword of honour to Suhaimi Zainul-Abidin (whom Jom has profiled).

With Konfrontasi and post-war bedlam now distant memories, the SAF probably recognises that the real threats are not the Malays across the waters or those on our shores, but cyber attackers, terrorists and others operating in opaque transnational networks. Lawrence Wong, prime minister, also appears more eager than his predecessors to cultivate ties with our immediate neighbours. The symbolism of last week’s parade, with Iskandar crashing across the sky as Firdaus marshalled troops on the ground, perhaps reflected all of that. There’s still a long way to go, of course. The SAF and police refuse to release detailed statistics on Malay officers in their ranks, just as the prison department refuses to release the ethnic breakdown of its population. We can postulate why: Malays are probably (severely) underrepresented in the former and overrepresented in the latter. Even as society must keep working through these knotty issues, we can nonetheless appreciate what has changed. “My heart swelled with pride,” said Muhammad Faishal Ibrahim, acting minister-in-charge of Muslim Affairs.

Society: Blue basket blues

Hawkers at the Bukit Canberra Hawker Centre have to pay S$70 a month to rent a Backyard Cluster space (0.48sqm); and are contractually obligated (“shall participate”) to offer 60 free unsubsidised charity meals a month. These facts rankled KF Seetoh, founder of Makansutra and arguably Singapore's most prominent food critic. In the lead up to National Day he (rightfully) called out the operator, Canopy Hawkers Group Ltd. “Ever tried asking restaurants in govt owned establishments to offer $10 banquet or buffet meals?” he wrote, on August 8th. “At 60, we ought to know how we can help the poor without exploiting those who struggle to sell affordable food.” Seetoh’s post sparked ruminations across social media.

Ong Ye Kung, health minister whose constituency includes the hawker centre, responded this week, with a mix of explanations and a strawman argument. Ong said that Seetoh’s claim that the S$70 was for the use of a blue basket was “not true”. Seetoh didn’t actually say that—he had clearly referred to the “space suppliers use”. But alas, with the mainstream media repeating Ong’s mischaracterisation, it’s simply the latest example of how truth gets mangled in our society. (The Online Citizen unravelled the informational nugget’s meanderings through cyberspace.)

Nevertheless, Ong said he appreciates “KF Seetoh’s concern for our hawkers”; and that we should keep “hawker culture alive and thriving” without “putting down anyone, whether they are patrons, hawkers, the hawker centre operator, or government agencies.” (Yes, skins as thin as popiah need caressing.) Seetoh thanked “Min Ong” for responding, and on Wednesday said that this “should be a masterclass moment to unite, not divide the people of Singapore.”

Throughout, Seetoh complained about poor coverage by the media, though he did laud one piece by The Straits Times, “Doing charity, encouraging healthy eating, adhering to onerous rules: Is too much being asked of hawkers?” Its title captures our dilemma. Ultimately, without fundamentally addressing inequality in Singapore, we’re stuck in a situation where the incomes and needs of the poor prevent hawkers from raising prices. The incident is a startling reminder that behind our cultural triumphalism and glorification of cheap food—commodified and packaged to draw Dua Lipa, Bill Gates, and Asia’s masses alike—is the lived reality of individuals who suffer and struggle at the behest of landlords, squeezing them of another S$70 a month.

Society: Made in China, consumed in Singapore

Shifts in consumer sentiment here have turned many Chinese brands into household names, driven by value-for-money and affordability. Once dismissed as inferior, China-manufactured goods, from appliances to smartphones and cars, are now edging out Japanese and Korean products long prized for safety, reliability and design. Electric vehicle (EV) maker BYD, for instance, leads the charge on our roads, outselling Toyota and even Tesla, its main EV rival, to become Singapore’s top-selling car. The appetite for Made-in-China extends to our tables. Last year, research firm Momentum Works found that Malaysia and Singapore host the largest concentration of Chinese food and beverage products in South-east Asia.

Tech firms like Byte Dance, Alibaba Cloud and Tencent have also set up regional headquarters in the city-state—further proof of Singapore’s bankability as a testbed for worldwide expansion. (And also as a place to sanitise reputations in the face of Sinophobia and protectionism, in what’s commonly called “Singapore washing”.) Chinese chains are “creative, quick to innovate and set food trends,” Thahirah Silva, a healthcare worker, told Al Jazeera (AJ). Also speaking to AJ, Samer Elhajjar, of the National University of Singapore’s marketing department, said that the stigma surrounding Chinese products is fading, with many brands perceived as “cool, modern and emotionally in tune” to the material desires of the young. “They feel local and global at the same time.”

If this surge of consumer warmth feels familiar, it’s because China is simply the latest in Singaporeans’ East Asian love affair. Japan has been among Singapore’s top trading partners since the 1980s, its retail and electronics giants—Yaohan, Isetan, Sony and Philips—long woven into local life (even if some have since left our shores). Its cultural imprint also runs deep, from Japanese anime, manga, and J-pop. Then came Korea’s own soft-power juggernaut. Emerging in the late-1990s and early 2000s, Hallyu reshaped economic ties, fuelling imports of cosmetics, electronics, and automotive brands, some developing a strong presence in Singapore—Samsung, LG and Hyundai Motor. Alongside this came a growing Korean diaspora, heightening the visibility and accessibility of Korean products. This is most vivid in the Tanjong Pagar area, nicknamed “Little Korea”, for its dense cluster of restaurants and grocery stores.

Since 2013, China has been our largest trading partner, with bilateral trade hitting S$170.2bn last year—more than triple Japan’s and double Korea’s. On his first state visit to Beijing as prime minister, Wong called the relationship “more important than before”, especially amid US tariff uncertainty. Yet managing domestic concerns—over cultural erosion, soaring property prices, and the rise of “born-again Chinese”—will be key to ensuring our affinity for Made-in-China extends beyond what we buy to those we live beside.

History weekly by Faris Joraimi

We jabber a lot about colonialism here at Jom, and how Singapore’s official history still has colonial blindspots. That doesn’t mean we overlook how anti-colonial rhetoric is also mobilised, by other governments, for political ends. Earlier this year, the Indonesian government under Prabowo Subianto announced plans to write an official history textbook. It was to be completed in time for Indonesia’s 80th anniversary of independence from Dutch rule, this Sunday, August 17th. But this week, the government decided to postpone the launch till November. The Ministry of Culture insists the project is necessary to form a strong national identity, address current challenges, and “eliminate colonial bias”. It’s the perfect allergen for academics, journalists, and human rights activists, who oppose this scheme of selective memory led by Fadli Zon, culture minister and Prabowo loyalist. Before steaming ahead, the government generously circulated a 30-page draft outline of the 10-volume history to journalists and historians.

The reviews were not fresh. Among the glaring omissions are the 1928 Women’s Congress, the financial crisis in 1997 that brought down Suharto, and the subsequent 1998 massacre and sexual violence, mainly targetting Chinese-Indonesians. Conveniently, these events implicate Prabowo, a key figure in the Suharto regime. Also absent is the 1955 Bandung Conference, a significant event in world history. Indonesian historians Bonnie Triyana and Asvi Warman Adam allege a lack of transparency in the project and called it “historical manipulation”. But 113 historians and archaeologists are involved in it, so not a few Indonesian scholars think it’s a worthy cause.

My favourite response is from Peter Carey, a historian of colonialism in Java and the rebellion of Diponegoro (1785-1855). “If you’re concerned about history, you wouldn’t be writing national history,” he said on the “What is Up, Indonesia?” podcast. “You wouldn’t be having Pahlawan Nasional [National Heroes]. You would actually be putting into the public domain [...] as much as possible of the raw materials, the raw sources… and it would be for you to make up your minds, to write your histories.” Singaporeans have similarly called for a Freedom of Information Act to enhance access to archival sources. Without that, it’s hard to have fair scrutiny of the national narrative.

Tech: A Sea of green, for now

The champagne was certainly flowing for some investors in Singaporean tech giant Sea as share prices popped 19 percent to US$174 (S$224.7), a stunning reversal of fortunes from its brutal 2022 collapse to US$34 (S$43.5). That coincided with double digit year-on-year revenue growth in the second quarter of 2025 across all three of Sea’s business units—e-commerce platform Shopee, game publisher Garena, and its fintech business Monee. Investors’ exuberance was largely driven by the 418 percent earnings surge, from US$79.9m (S$102.3m) to US$414.2m (S$530.4m). CEO Forrest Li’s aggressive cost-cutting has transformed Sea from a cash-burning gambler into a disciplined operator. But key contributors to the strong growth also carry potential risks. For instance, Monee's breakneck lending expansion risks scrutiny from increasingly strict Indonesian regulators, and Garena is desperately milking Free Fire, a seven-year-old game, for another payday in a world where consumers are constantly seeking new content. In the ongoing war of attrition among e-commerce giants, the champagne could yet run dry.

Business: Can Ninja Van hang on?

Just four years ago, Ninja Van was riding high as South-east Asia’s logistics darling. The Alibaba-backed unicorn was valued “well north of US$1bn (S$1.28bn)” after its 2021 US$578m (S$739.67m) Series E funding spree. Today, the company is a case study in post-pandemic reckoning: a further 12 percent of Singapore staff cut following layoffs in April and July last year, a halved valuation in its latest US$80m (S$102.8m) funding talks, and a desperate shift in focus from e-commerce logistics to tech-driven B2B and cold chain services. The cracks in Ninja Van’s armor are widening fast.

Behind the corporate speak about “streamlining headquarters functions” lies a troubling reality: South-east Asia’s delivery wars have entered the trenches. With J&T Global Express (and its S$2.56bn warchest) and Sea’s SPX Express turning the region into a margin-crushing battleground, Ninja Van’s new forays into tech-driven B2B restocking and cold chain logistics are bets to increase the value of the extensive delivery network it has built up with its e-commerce logistics business. But this strategic shift comes at a human cost. While affected employees get severance packages aligned with Singapore’s tripartite guidelines (plus extended medical and mental health support), the repeated layoffs reveal an unsettling pattern of instability. The math no longer works. Even though Ninja Van now delivers 2m parcels daily, its former valuation is no longer justifiable, with investors demanding preferential exit clauses. The latest round of funding may have given the company a lifeline, but how long can it hold on?

Faris Joraimi, Abhishek Mehrotra, Sakinah Safiee, Tsen-Waye Tay, and Sudhir Vadaketh wrote this week’s edition.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.