Our picks

Politics: Glee

Some expected gloating at the recent People’s Action Party (PAP) Awards and Convention, the first party shindig since May’s electoral success. Lawrence Wong, party secretary-general and prime minister, spoke with relish of the well-wishers who apologised after GE2025 for having doubted the PAP’s chances. “We should have more confidence in you,” confessed those of little faith. He also blamed the opposition for portraying the global cost-of-living crisis as a local one—never mind that academics have repeatedly pointed out local factors too—stoking “anxiety and frustration”. But Singaporeans saw through such chicanery. “They tell me, ‘Thank you for the vouchers. Please give us more.’” Wong tittered, and the assembly tittered with him, jubilant aristocrats smug in their own largesse towards a society dependent on handouts.

More puzzling was when he spoke about the PAP’s win in Tampines GRC. A loss there “would have signalled that the Workers’ Party’s [WP’s] calculated appeal to the Malay-Muslim community had been effective.” Presumably, he meant the WP’s decision to move Faisal Manap from Aljunied to lead its Tampines team against the one led by PAP’s Masagos Zulkifli, then Minister-in-charge of Muslim Affairs. The affrontery. How dare a party strategise for an election. You wouldn’t catch the PAP parachuting two young working mothers to wrest an opposition GRC full of young families. And there’s no way they would move a deputy prime minister from a constituency where he’s walked the ground for two decades to one he has no connection with, to stymie a strong opposition team. “The opposite of making a calculated move is to make an uncalculated, random, or unthoughtful move,” wrote Ian Chong, NUS academic, wondering which political party worth its salt would do that.

Maybe Wong was hinting at the Noor Deros episode. That’s a distraction. The PAP was nearly unseated by first-time opposition—it won by around 6,000 votes in a 148,000-strong GRC—because, as observers have noted, there was discontent over the tudung issue among others, and because the WP fielded high-calibre, non-Malay candidates too. Framing GE2025’s closest contest in ethnic terms was reductive as well as insulting to the tens of thousands who voted against the ruling party, to say nothing of the efforts of its own popular leaders like Baey Yam Keng. Much of this was mere speechifying, the release of nervous energy with comrades who’ve helped the party to a historic win in a tense election. But always, from behind the platitudes and the gratitude, the overt humility and modesty, sticks out a dominant strand in the party’s DNA: support is wisdom; dissent, folly.

Politics: No surprises

Lee Kuan Yew’s primary dying wish, as stated in his will, was for his house at 38 Oxley Road to be demolished; if “changes in the laws” prevented that, his secondary wish was that “the House never be opened” to the public. It would appear like the PAP is set to disregard the first, and possibly even the second, depending on one’s reading of the will, and the site’s eventual use. Would Lee have wanted visitors entering any part of the structure if traces of private spaces are removed, as the government intends to do?

Regardless, one way to interpret the national monument gazettement order is that no individual’s interests can supersede the country’s. Another is that the PAP is so reliant on Lee’s legacy that it’ll act against his wishes, as well as that of his wife’s, two of his children, and most Singaporeans surveyed on the issue, in order to cling to any remnant of it. There is probably some truth to both narratives, though it would be unfair to depict it purely as a power play. People across the political spectrum, including architect Tay Kheng Soon, have supported preserving the structure, built just before 1900.

Lee Hsien Yang, his younger son and owner of the house, had earlier applied to demolish it, in keeping with his father’s desire, and vowed to “build a small private dwelling, to be held within the family in perpetuity.” He would seemingly not have benefited financially from the property. Now that the government intends to preserve the site, it will have to acquire it from him—and so presumably he will. (He has till November 17th to lodge an objection.)

What else does the entire saga reveal about us as a people? “The bougainvilleas outside”, Jom’s commentary this week, is our meditation on the issue.

Society: The real shrines

It is an area steeped in this city’s multicultural history. The Hokkiens called it “Tek Kah” for the bamboo clumps that once thrived there. The British reared cattle there—or rather, asked Indians to do so—leading to the Malay, “Kandang Kerbau”. Later “Farrer” would be scripted in, honouring a colonial administrator. And finally, as cultural commodification par excellence for a developmental state, “Little India” was born. It is a place-name palimpsest to titillate the CMIO gods.

It’s also where generations of women gave birth. In 1858, Singapore’s fifth “General Hospital” was built there, consisting of the Seamen’s Hospital for Europeans, and the Police Hospital for locals. In 1865 it began treating women for gynaecological conditions and childbirth. Among its more notable episodes in those early decades was a cholera outbreak in 1873, during which, the adjacent Lunatic Asylum, overcrowded, sent “53 of the quiet and well-behaved lunatics” to the hospital’s empty buildings. In 1888, Singapore’s first dedicated maternity hospital opened on Victoria Street. Amidst high rates of maternal deaths and infant mortality, pressure grew for a second. In 1915, when the Midwives Ordinance was passed, just under 16 percent of confinements were attended by trained midwives. (Midwife training was a key remit of institutions.) On October 1st 1924, a new free maternity hospital opened in the former General Hospital’s premises at Kandang Kerbau (henceforth KKH). It grew over the decades, never ceasing operations, even under the Japanese, who called it Chuo Byoin (Central Hospital) and maintained Benjamin Sheares, future president, as deputy medical superintendent. In 1965-6, while Lee Kuan Yew wept over the loss of his greater kingdom, his subjects multiplied. In 1966 alone, KKH delivered 39,856 little terrors—one every 13 minutes—more than any other hospital globally, and a Guinness record it’d hold for 10 years. (“Stop at two” would be born soon after.)

KKH and its generations of midwives are a big reason why the death of a newborn, an intensely depressing human experience, is almost non-existent here a century later. (Infant mortality has dropped from 347.8 per 1,000 births in 1908 to 1.7 today.) One of KKH’s most famous gynaecologists was Dr Yvonne Marjorie Salmon, who over a 44-year career was involved in the first surgery, in 1961, to separate Siamese twins. She began work there in 1953, three years after her father, Dr SR Salmon, had opened his own private maternity hospital on nearby Prinsep Street.

The tiresome hullabaloo over Lee’s house has sadly overshadowed these other landmarks. On October 1st, 101 years after it was founded, the former KKH building was gazetted as a national monument. (The hospital moved across the road in 1997.) And this week, we learned that the former Salmon’s Maternity Home, an art-deco building, would be converted into a museum, school and cafe. The geographic distance from the secluded, single-lane, stodgy Oxley Road, named for a colonial surgeon, to that effervescent, dense urban mash whose origins are in bamboo and buffalo, is a little over a kilometre. The spiritual distance is maybe too much to contemplate.

Society: Youngsters like to buy now, pay later

This week, bargain hunters probably spent hours scouring Shopee for the best 11.11 deals: portable fans, massage guns, hydrating serums, perhaps a Guess wallet from last season’s catalogue. As they clicked “add to cart” and the numbers climbed, many would have drawn comfort from SPayLater, allowing them to split the cost into installments, with the initial payment a fraction of the total. Buy now, pay later (BNPL) has become ubiquitous not just on online shopping platforms but also on superapps like Grab where customers can defer paying for car rides, food, and groceries. BNPL service providers make money from merchants and customers’ late fees without charging compounding interest rates like credit cards. BNPL is also more accessible, with “soft checks” that only require customers to be 18 to access up to S$2,000 without going through a means test. All of which means that consumers tend to spend more, and hold multiple concurrent debts under BNPL schemes.

Such deferred payment plans help those from low-income families to access vital needs; they can also spur impulsive spending by making repayment a problem for the “future you”, forgetting that affordability isn’t measured by what’s in one’s pocket today but by the number of paychecks needed to completely pay off a purchase. Some worry that the industry preys on the young especially, exposing them to debt before they are fully independent. A 2024 Worldpay report found that 77 percent of Gen Zs used BNPL—by far the highest among all age groups surveyed. Some point to their habit of purchasing a “little treat”—small indulgences woven into everyday routine as a reward or coping mechanism. But this culture of self-reward isn’t just frivolity; it’s shaped by a sense of fatalism. Confronted with climate anxiety, global turmoil, unaffordable housing, and a relentless rise in living costs, many young people turn to small luxuries as quick fixes for a heavy reality. Perhaps what they need is not only stricter financial discipline, but also a renewed faith that the future is still worth saving for.

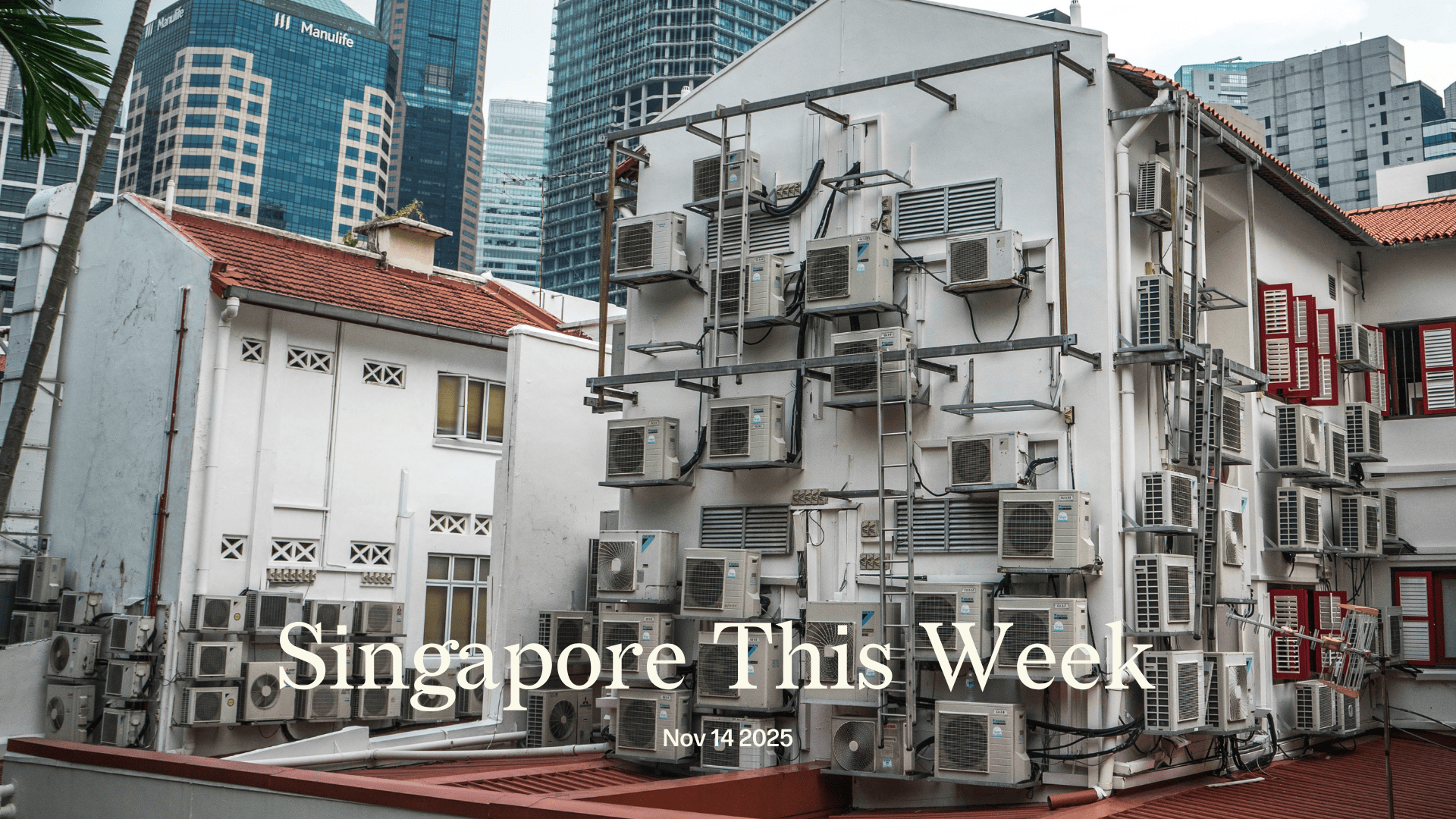

Earth: Cool it! But make it sustainable

The “humble” air-conditioner, hailed by Lee Kuan Yew as one of the “signal inventions of history”, has been credited for transforming Singapore into today’s thriving metropolis. In the past decade, however, this emblem of modern comfort has taken as much heat as it dispels for its role in global warming and the Urban Heat Island effect, which can raise city temperatures by up to 10°C above surrounding rural zones. A 2022 study estimated that the energy needed to power air-conditioners generates about four percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, while refrigerants in these machines, such as hydrofluorocarbons, are themselves potent climate pollutants. In the city-state, air-conditioning accounts for a major share of building energy use, and buildings make up more than 20 percent of the nation’s carbon emissions. “We cannot air-condition our way out of the heat crisis,” warned Inger Andersen, UN under-secretary-general and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) executive director. Andersen was speaking at the ongoing COP30 UN climate talks in Brazil. While cooling “saves lives and determines whether economies, schools and hospitals function”, she noted that if delivered unsustainably, it deepens inequality and risks grid collapse. To help cities meet this challenge, the UNEP’s Global Cooling Watch report outlines a Sustainable Cooling Pathway that could cut cooling-related emissions by 64 percent by 2050, saving up to US$43trn (S$55.9trn) in electricity and infrastructure costs. The plan prioritises passive and nature-based cooling solutions—shading, natural ventilation, reflective surfaces, and green corridors; low-energy cooling like fans; greater efficiency; and a global phase-down of climate-warming refrigerants.

Singapore was among the 185 cities in Brazil who pledged to curb unsustainable cooling practices. The situation is particularly urgent here: the island is heating up twice as fast as the rest of the world. In response, the government has mandated that by 2030, all HDB blocks will be coated with heat-reflective paint, shown to reduce ambient temperatures by up to 2°C. Similar approaches are being used in India and Bangladesh, where roof coatings help cool low-income settlements and slums often built using corrugated iron. In Guangzhou, China, urban greening, through water bodies, parks and ventilation corridors, has helped reduce temperatures and heat stress.

Lee was right: cooling is essential. It sustains communities, food systems, and city life itself. Yet, managing the “growth paradox”, the tension between development and climate adaptation, will define Singapore’s future. Beyond sustainability also lies equity: over 1bn people are at high risk of a lack of access to affordable, sustainable cooling. Achieving thermal justice means asking, simply, who gets to stay cool, and who must endure the heat?

Some further reading: “Can microforests cool Singapore?”

Arts: Artist’s proof

Whether it’s a graceful swoop or a wobbly squiggle, this is a mark that marks us all. We leave it on contracts and receipts, on birthday cards and attendance sheets. Our signature both confirms identity and creates value; that glyph in a canvas corner, or on the title page of a manuscript, might mean the difference between a replaceable reproduction or the real thing. Why do we invest so much in the signature? “...in giving a signature, persons are ...not only giving a representation of themselves,” writes academic Tilman Richter, “but...expressing something that is connected to their authentic self”. He explains: in Europe, the signature originated from the idea of writing as a private act, as a manifestation of a writer’s inner life. The signature becomes a paradox, both a private expression and a public representation of a self. And when it enters the public realm, usually as an autograph, it’s a representation that not only proves provenance, but also offers proof of proximity to the real thing.

And hundreds of people wanted this public representation of privacy from genre-hopping literary rockstar RF Kuang, one of the headliners at the ongoing Singapore Writers Festival. The 29-year-old’s book signing at Victoria Theatre last week caused a minor stampede. Singaporeans, who love a good queue, were met with the lack of one. No one knew where the line ended, or began; ushers formed a human barricade; those who had tickets to her keynote, desiring priority access, complained about interlopers who didn’t. Frustrated fans ranted on social media that the one-book and no-photo policy hadn’t been communicated well. This didn’t bode well for those who, according to a disgruntled fan, “brought suitcases full of books” so they might be transfigured by Kuang’s touch. Yet a book signing isn’t just about acquiring the mark of authenticity. It embodies another paradox: a public moment of intimacy with a writer whose book—which you’ve pressed to your heart, stroked with your hands—is now a portal to the person themselves, a moment to share a shy delight and have that enshrined in the very object that transported you beyond the walls of your own world. Kuang’s events weren’t the only packed ones. Readers were sated at food writer Fuchsia Dunlop’s salon, as she dished out vignettes over canapes at Belimbing restaurant; another session on local political humour rode the wave of the recent GE, which made social media stars out of young journalist duo “Gerry and Mandy” (Christie Chiu and Wong Yang of The Straits Times). The festival coincided with another significant announcement: that the SG Culture Pass can soon be used to purchase Singaporean literature, and tickets to local films at the upcoming Singapore International Film Festival. Should we be relieved—or disappointed—that none of our own yet causes a Kuang-ish crush?

Some further reading: if you’d like to get a little closer to the creators of Jom’s annual Print Issue No. 3, it includes the signatures and sign-offs of every single contributor. Now available in our webshop.

Abhishek Mehrotra, Sakinah Safiee, Corrie Tan, Tsen-Waye Tay, and Sudhir Vadaketh wrote this week’s issue.