Our picks

International: An ultimatum masked as a proposal

Last Friday, the US Embassy in Singapore hailed Donald Trump as “The President of Peace”, supposedly ending seven wars in seven months—including between Cambodia and Thailand, and India and Pakistan. The Facebook post garnered over a thousand reactions, the vast majority with a laughing emoji. A few days later, he announced “potentially one of the great days ever in civilisation”. Along with Benjamin Netanyahu, Israeli prime minister, he’d concocted an “extremely fair proposal” for peace in Gaza. Both are under intense pressure as condemnation for the genocide mounts: more than 150 of the 193 UN members now recognise Palestine (not Singapore); dozens of delegates walked out when Netanyahu addressed the UN General Assembly last week; and the EU is weighing a partial suspension of its free trade agreement with Israel.

An end to hostilities would ease Israel’s isolation, though its shame will linger far longer. The domestic calculus for Netanyahu is complex: the plan is supported by most Israelis but not by all members of the far-right on which his coalition rests. With elections due next year, and a major corruption case hanging over him, Netanyahu will continue supporting the plan if it serves his interests. If not, he may backtrack and blame the Palestinians. Meanwhile, more Americans now favour Palestine for the first time in the three decades the New York Times has polled the issue. Trump’s own ratings have been steady of late, but at a level lower than most predecessors at this stage in their terms. With bruising midterms due next year, Republican strategists will take any fillip they can get. Peace in the Middle East would be one.

Still, how realistic is the Trump-Netanyahu plan? Not very. A hostage exchange is mooted but Israel, while barred from occupying or annexing Gaza (and Netanyahu would never violate those terms, for Netanyahu is an honourable man), is not required to withdraw its forces from the region as the exchange happens. Though the plan has been endorsed by many Arab and Muslim states, including Hamas’s sponsors Turkey and Qatar, there was no Palestinian involvement. Hamas, Gaza’s governing body since 2005, and the perpetrator of the October 7th attacks, has been handed a fait accompli, with Trump giving it “three or four days” to respond and Netanyahu resorting to the “easy way or the hard way” rhetoric more befitting a thug. And since the plan sees no role for Hamas in Gaza’s future, it’s essentially an ultimatum for the outfit to sign its own death warrant.

“It’s a deal Hamas would be foolish to accept,” said John Mearsheimer, a political scientist. Beyond Hamas, said Mearsheimer, there is “no sense of self-determination” for the Palestinians. Instead, governance would be handed to a “technocratic and apolitical Palestinian committee” overseen by a “Board of Peace” led by Trump and possibly including Tony Blair, Iraq warmonger. So far, so Orwellian. Those claiming to want a two-state solution and supporting the plan, including Singapore, have probably been had. “Gaza,” said Mearsheimer, “won’t be governed for a long time by the Palestinians…but maybe most importantly, what’s the endgame here? Are the Palestinians going to get a state of their own? No.”

Politics: Law-abiding state

Singapore refused entry to self-exiled Hong Kong pro-democracy activist Nathan Law on September 27th, saying his presence was not in the country’s national interests. Despite holding a short-term visa, Law was questioned at Changi Airport and placed on the earliest flight back to San Francisco the next day. The Ministry of Home Affairs explained that a visa holder is “still subject to further checks” at Singapore’s point of entry. Law told Bloomberg that it was the first time he had been blocked from entering a country, speculating that the “U-turn” was either because of Chinese pressure or Singapore’s own political considerations. Law was possibly due to attend a closed-door event reportedly linked to the Washington-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

One of the student leaders of the 2014 Umbrella Movement, Law fled Hong Kong in 2020 just before Beijing imposed the sweeping National Security Law (NSL). Now living in Britain under asylum, he is wanted by Hong Kong authorities, who in 2023 placed a HK$1m (S$165,500) bounty on him and seven other activists. John Lee Ka-chiu, chief executive, said that no country should harbour criminals and warned that fugitives would be pursued for life. He declined to say if Singapore had been asked to transfer Law. Extradition requests can be refused under the 1998 agreement between the two former British colonies, for instance if offences are of a “political character”.

The case highlights Hong Kong’s shrinking freedoms since the 1997 handover, when Beijing pledged under “One Country, Two Systems” that the city would retain autonomy for 50 years. In reality, civil liberties have eroded: electoral reforms curtail democratic participation, activists and journalists are prosecuted, and the NSL criminalises dissent even abroad. Domestically, Singapore has long warned against importing foreign politics. Support for Hong Kong’s protests here was mixed. Some Singaporeans expressed sympathy, but didn’t condone “senseless and lawless violent actions”. Many in the older generation disapproved of the demonstrations, perhaps viewing them as disruptive or too radical. The city state has barred controversial figures before, among them Indonesian preacher Abdul Somad Batubara and political scientist Huang Jing, but those involved perceived national security threats. Law’s case is reminiscent of the time in 1908 when colonial Singapore rejected Peking’s request to deport Sun Yat Sen.

Analysts suggest that barring Law allowed Singapore to sidestep a political predicament: extraditing him risked criticism from the West—the US has accused Hong Kong of transnational repression—while admitting him risked antagonising Beijing. Ronny Tong, Hong Kong barrister and government advisor, called the decision a “middle ground” avoiding confrontation with the UK and the US, while also not offending China and Hong Kong. Besides, as one online commenter noted, “Sounds like Singapore was doing him [Law] a favour.”

Society: Supporting low-income mums

“Fertility is a gift with an expiry date”, rang a fertility ad plastered on the walls of City Hall MRT in 2016. Online, Singapore Cancer Society urges young people to get HPV vaccination because “ovarian cancer is a silent killer”. In school, teenage girls cringe through awkward sexual health talks by overworked teachers preaching about abstinence. Too often, conversations about women’s health focus on preventing unintended pregnancies, managing infertility, or screening for diseases. While important, there is not enough talk on the ways gendered norms and material conditions (like financial stability) can intersect to impact women’s health outcomes, specifically on maternity.

A local study has advocated that maternal and children’s health should be examined through a life course approach—across preconception, pregnancy and postpartum phases—and interventions should not be seen through just individual choices, but the sum effects of interpersonal, community, and policy factors. The Pregnant Mum and Baby Nutrition Programme by KidSTART, a government-organised NGO focused on early childhood development, is a step forward in this direction. With a S$6.5m donation by the DBS Foundation, it’ll enable over 2,200 pregnant women from low-income backgrounds to receive care packs, grocery vouchers and mental health support from pregnancy to their child’s first year. Such an initiative is vital as another study found that mothers from lower income households are more likely to exhibit symptoms of higher antenatal mental health problems, and those with such symptoms were more likely to have children with poorer readiness for school.

While early interventions are key to reducing inequality, women from low-income backgrounds often avoid formal support. Their reluctance is shaped by internalised narratives that stigmatise poverty in the context of motherhood. In Singapore, we may also still experience the lingering effects of policies like the Graduate Mother Scheme, which shaped societal attitudes about who’s deemed “deserving” of having children. As a result, many such women turn to informal sources of advice, such as social media, rather than accessing professional or institutional help. The programme will be doubly successful if it can uplift and empower them.

Earth: The seer who in the forest found us

A white woman in her khaki safari shirt and shorts potters around the tropical Tanzanian rainforest, her blond hair pulled back and her freckles catching the sun. She lifts up her binoculars and stares; a smirk forms, then a smile. Soon we see the chimpanzees who’ve become her family, who’ve helped her explain the interconnectedness of primates through our behaviours. Having observed David Greybeard—names, not numbers, she insisted—using a grass stem to extract termites from a mound, she knew that humans weren’t the only ones to use tools, perhaps the most notable of her discoveries, which would later be called “one of the Western world’s great scientific achievements.”

Because all the primatologists then were men, Jane Goodall had to scale academia in reverse: fieldwork first, classroom second. In 1961, she became only the eighth doctoral student accepted by Cambridge without an undergraduate degree. National Geographic published her first masterpiece in 1963, with photographs taken by the man she’d later marry. It released “Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees” in 1965, the first of over 40 films she’d be in. So seared in our global imagination are those visuals that countless other female primatologists she inspired would be mistaken for her. Never again would a young female researcher have to worry about not being taken seriously in the forest.

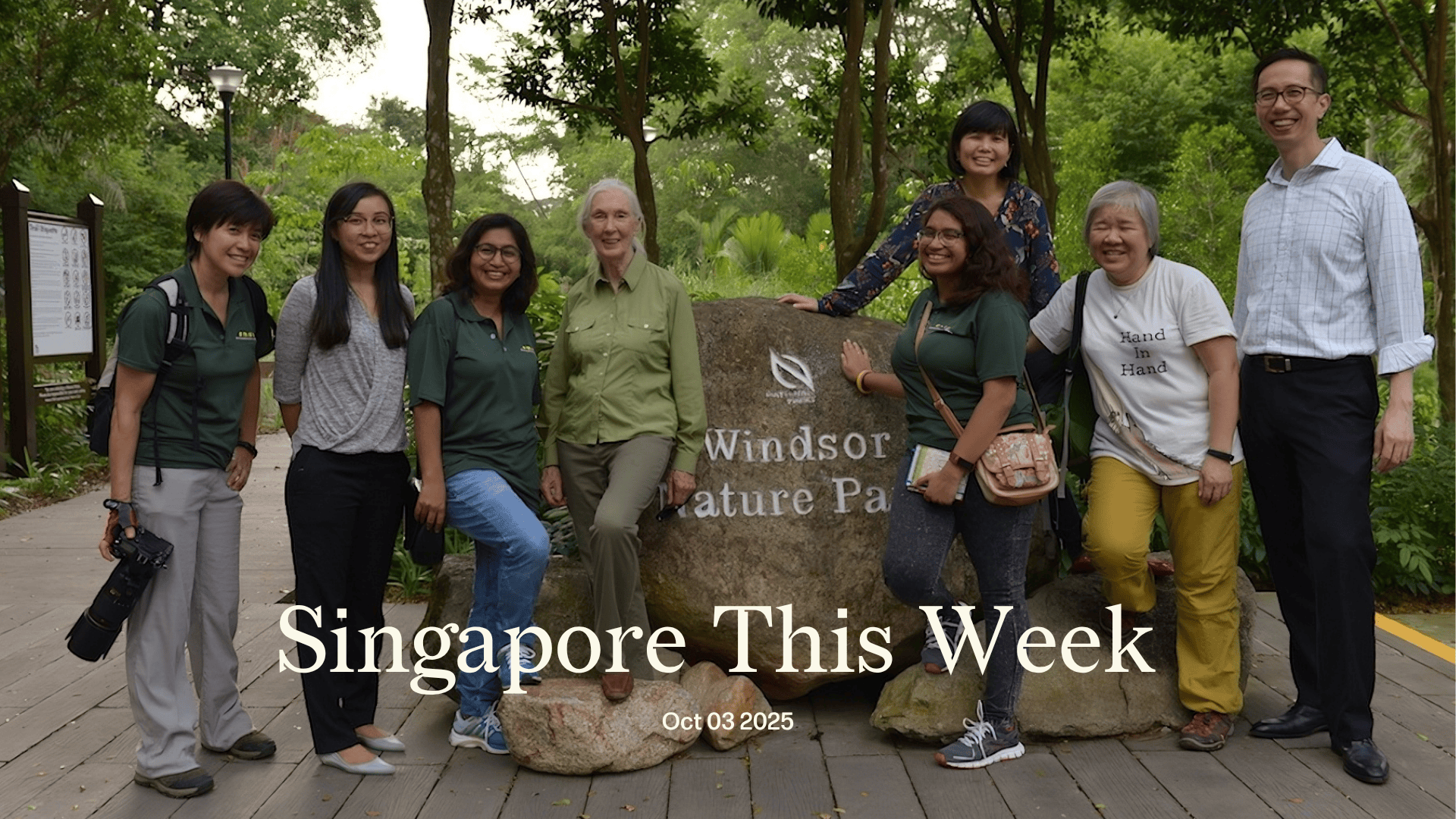

After she’d shattered gender stereotypes through her instinctive grasp of mass media, she taught us how best to leverage celebrity. With a disarming, delicate demeanour, she relentlessly spread her gospel, making over 300 public appearances a year, right up to her death this week at 91. The Jane Goodall Institute, operating in over 25 countries, inspired millions of young people not only to understand the more-than-human world, but simply to believe in their own capacity for change. Its Singapore chapter opened in 2007, helping us live better alongside our long-tailed macaques, partly by reminding us that, whether on the edge of Bukit Timah or MacRitchie, we are the ones encroaching on their territory. Andie Ang, its current president, established herself through work on the critically endangered Raffles’ banded langur. Every time Ang speaks, she channels Goodall, and helps us ponder a 60-year spiritual journey from one equatorial country to another.

What else did Goodall teach? Doom and gloom awaken us to decimation, but “if you don’t have hope, why bother?” Evangelise gently, keep channels open, because “people have to change gradually”. Good zoos are good, partly because the wild, where other human threats exist, isn’t always a utopia for animals. And she called the forest “a temple, a cathedral of tree canopies and dancing light”; and there she felt close to a “great spiritual power”, existing in every living thing, which for lack of a better name she calls “God”, and from which she draws much strength. When Goodall was alone in nature, there were times “when for a moment you forget you’re human. Your humanness goes away, and you’re part of that natural world. It’s the most amazing and wonderful and beautiful feeling.”

Donate to the Jane Goodall Institute Singapore.

History weekly by Faris Joraimi

After a long delay, Joseph Christiaens finally got the engines of his Bristol Boxkite biplane roaring. He climbed into the seat, as men of the Royal Engineers, trousers flapping before the spinning propeller, let go of the machine. A hundred yards later, it rose. But something didn’t feel right. After climbing to about 10 metres and sputtering on for 400 yards, the wiry contraption landed abruptly. A second and third try were not much better, and the Belgian aviator explained to disappointed paying spectators that the weird local atmosphere was to blame. The warm air was less dense than the cooler air in Europe; as a result, the aeroplane had lost lifting power. Encouraged by friends, Christiaens went for a fourth attempt. The sun having set over the Serangoon Road race course, the elements now worked in his favour as he rose higher—to about 30 metres—and flew a steady 200 yards further than before. From the edges of the field, the “native crowd” of thousands erupted in cheers. It was March 1911, the first demonstration of human flight in Singapore.

The “aviation meeting”, organised by the Singapore Sporting Club and promoted by the Societé d’Aviation d’Extreme Orient, was a highly-anticipated three-day affair, and part of Christiaen’s tour of the East Indies. Newspapers printed detailed specifications of the proudly British-made biplane, as worldwide excitement grew around the viability of regular air transportation (and its military applications). Reaching Singapore, the demonstration would resemble Europe’s fashionable high-society aviation meetings, like the one colourfully painted by Franz Kafka in “The Aeroplanes at Brescia” (1909). Admission was charged, and for 50 Straits dollars you could even be a passenger. Obviously, only colonial elites and people of means could afford it. Like the Brescia event, the glamour of flight at Serangoon was punctured by technical challenges, with the press reviewing it as an unsuccessful premier with a mediocre showman for a pilot.

This was science as popular entertainment. Lukewarm reception led to poor financial takings for the promoters, who were especially annoyed that the “several thousand natives” who saw the flights “were admitted to the ground without paying a cent”. Boo-hoo. Better policing was suggested. But too bad the nearby Mount Emily (or reservoir hill) offered a free panorama of the grounds too, making it harder to exclude unpaid subscribers. Wrote one journalist, “It can be left to those who take advantage of it at the expense of those who do not, to wrestle with their consciences.” Today, watching planes take off and land at Changi is a beloved pastime, but those in the jets should wrestle with a contemporary dilemma: the privilege of air travel whose costs accrue to those worst affected by the climate catastrophe.

Arts: “And soul of a thing, just a second ago called a human being”

Last Saturday, a 38-year-old Malaysian—born in Ipoh, later bred in Singapore—published his debut poetry collection. He hadn’t started out as a writer; he’d dabbled in music, playing drums for the church band when he wasn’t working as a warehouse assistant, later taking up a job across the Causeway as a security officer while also studying part-time in a private school. Still, he’d landed a storied spot for the launch: Gerakbudaya, one of Malaysia’s most beloved indie bookstores. It’s long backed local authors, hosting both book talks and bracing debates on current affairs, and stocking hard-to-find regional titles in its floor-to-ceiling open shelves. A clutch of eager attendees made their way through the thick lattice of Petaling Jaya’s suburban streets to get their hands on a copy of the anthology, including K Saraswathy, the country’s deputy national unity minister. But attending his own launch was a luxury that the poet—who’d been chiselling away at his craft for over a decade—could not himself afford. Because he’s an inmate on Singapore’s death row.

Pannir Selvam Pranthaman was convicted of trafficking 51.84 grams of heroin across the Woodlands Checkpoint in September 2014. Since then, he and his family have submitted a range of petitions, challenges and appeals for stays of execution. He was first due to hang on May 24th 2019; his latest stay of execution was this past February. All this time, between one legal knot and the next, between one gasp of hope and another dismissal stubbing it out, Pannir wrote. He wrote sitting on the floor of his cell with a stack of court documents as a desk, and a spindly ink refill as a pen—because its sheath might constitute a weapon. His poems filtered out of the walls of Changi Prison bit by bit: in letters written on recycled paper, or recited to his sisters from memory. They compiled his verse and he revised it between visits. The result, Death Row Literature, is a years-long labour of love, with death as both catalyst and companion.

Last month, the Singapore courts again rejected Pannir’s appeal for a stay of execution. In its written judgment, the court penned its own disquieting rhyme. “[T]he state is entitled to deprive them of their lives,” so went its affectless euphemism, followed by a tepid disclaimer, “subject to the qualification that this must be carried out in accordance with law.” Pannir chose a different rhyming couplet. “Judging others is naturally easy,” he wrote. “Positions switched - we’ll have more mercy.”

Some further reading: In “The death penalty: seeking an honest conversation”, Jom’s editorial team interrogates deterrence and public opinion as justifications for retaining the death penalty—and makes the argument for abolition.

Arts: Keep calm and carry on

It’s 1914, and you’re a Vietnamese villager. The French forcibly recruit you for first world war logistics: you drive French soldiers to the frontline, then bear them back on stretchers. It’s 1988, and you’re a Burmese photographer. The resistance has a new leader, the willowy daughter of the revolutionary who gave your country independence—until it all ends in a violent, bloody coup; you have the opportunity to slip across the border and fly to Europe, and you do. It’s 2021, and you’re a teenager from India with a gift for art. The portfolio you’ve painstakingly compiled throughout secondary school grants you a scholarship to an art school in Singapore, a place you’ve never been. What do you carry with you? Two upcoming art exhibitions running through October and November wrestle with both the resources and the burdens that migrants carry with them to new lands. The annual “Women in Film & Photography” platform by Objectifs – Centre for Photography and Film features artists from across South-east, South and East Asia responding to the theme of “What We Carry”; indie arts organisation The Substation and the Asia-Europe Foundation have come together to present “Between Lands: Migration as Transformation”, centring artists from South-east Asia who are interrogating the experience of diaspora and displacement as shaped by both geopolitical tumult and the climate transition.

The spine of Objectifs’s upcoming season is an exhibition of eight artists exploring these migratory inheritances, whether that’s between geographies or between genders. Vridhi Gulati reflects on the complex socioeconomic contract of marriage in her work “Dahej”, a looped video projected on a black sari. In “Mekong – The Mother of Rivers”, Ore Huiying traces the waterways of the Mekong River through Laos and Cambodia, documenting the relationship between its riverine rhythms and the villagers who subsist on its banks, and provoking viewers to confront the ethical implications of environmental degradation and relentless development. And in “Boy”, Cy Liu experiments with self-portraiture and collaborative image-making to embrace his identity as a trans person, where photography becomes a practice for both acceptance and metamorphosis. Beyond what they carry with them, it’s what these artists deliver to us that transport us beyond the borders of our imaginations.

Some further reading: In “Movement as survival: the migratory paths of ‘Eclipse’ and ‘The Troupe’”, Aditi Shivaramakrishnan reflects on the journeys that both voluntary and involuntary migrants take in the wake of seismic events such as the Partition of India and Pakistan, and the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Faris Joraimi, Abhishek Mehrotra, Sakinah Saifee, Corrie Tan, Tsen-Waye Tay, and Sudhir Vadaketh wrote this week’s edition.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.