Dear reader,

Today, we’ve published our first-ever postcard from a Singaporean abroad: Amandas Ong, a London-based journalist, tells us about her experiences reporting from Ukraine. We also have a bumper issue of Singapore This Week, which includes our thoughts on a great new book by Anthea Ong, former nominated member of parliament, as well as a critique by Faris Joraimi, Jom’s history editor, of Jamus Lim, current member of parliament, for his somewhat affectionate reflections on the passing of Queen Elizabeth II.

I’d like to talk a bit about Lilibet and all the other blue bloods on this planet. My antipathy towards monarchs and hereditary positions was forged in Malaysia, where I have much family.

I’ve observed the grotesque hierarchy for years: the grovelling before royalty, the roadblocks on highways for princes racing their Ferraris, once even, while on a trip to Tioman, the utter disregard for people and property displayed by a member of Johor’s royal family. This drunk, young man threw bottles, scolded strangers, grabbed women, slapped acolytes, and generally behaved as if every molecule trapped within the imagined world that is Johor, from the downtown hookah bars to the leafy islets, belonged to him.

In recent years, amid their country’s ongoing political turmoil, many Malaysians have looked to their King as a source of stability, somebody who can rise above the apparent messiness of politics, a lodestar in unchartered territory. Many Thais do the same, even though in the throne now is an obnoxious playboy who rules from Germany. “Bike, fuck, eat. He does only those three things,” an insider told The Economist.

I often wonder if “commoners” hark back to some romantic, idealised past of their own making. In a globalised world of overlapping identities, many might see in the throne an exalted, if archaic, vision of nationhood, of belonging. But when exactly did royalty represent you?

In Malaysia, Thailand and elsewhere, crooked politicians and “benevolent” kings often rely on each other for survival. Najib Razak seeking a royal pardon is the latest example.

A common refrain from some European friends over the decades has been that their respective monarchies are far more genteel, approachable, and empathetic than those in South-east Asia. Which once made sense, and yet I’ve also grown to think that European royalty is just much better at PR.

Prince Andrew’s sordid shenanigans with Jeffrey Epstein would probably make Brunei’s princes blush, and yet he continues to be shielded by the British establishment. This past week King Charles III has, thanks to a 1993 deal with the government, managed to avoid inheritance taxes on an estate valued at over £650m (S$1.05bn), for which Brits would ordinarily be assessed at up to 40 percent.

Yet, the thing that really shocked the writer in me was British police arresting anti-monarchy protestors, some for proclaiming “Not my king” and one person for heckling Prince Andrew.

Memories of Thailand’s lèse-majesté law came flooding back. We used to have animated conversations about this in The Economist Group’s office in the late 2000s. One of the newspaper’s stringers even had to leave Bangkok after the publication of a brilliant but hard-hitting piece.

When one thinks about the chummy relationship between royals and politicians, the worst manifestation of it, whether in Thailand or the UK, is when the state prevents ordinary people from criticising the monarchy.

Perhaps the very idea that European royalty is morally superior to South-east Asian is a reflection of a colonial mindset.

Many have commented on the Empire’s sins. In “My Family Fought the British Empire. I Reject Its Myths”, writer Hari Kunzru reminds us that Elizabeth was Queen when British troops tortured Kenyans during the Mau Mau uprising and fired at civilians in Northern Ireland. “She spent a lifetime smiling and waving at cheering, native people around the world, a sort of living ghost of a system of rapacious and bloodthirsty extraction.”

In Singapore, The Straits Times dedicated vast real estate to Elizabeth. Parliament observed a minute’s silence. Numerous politicians, including Jamus Lim, shared fond memories. And state flags will be flown half-mast on the day of her funeral.

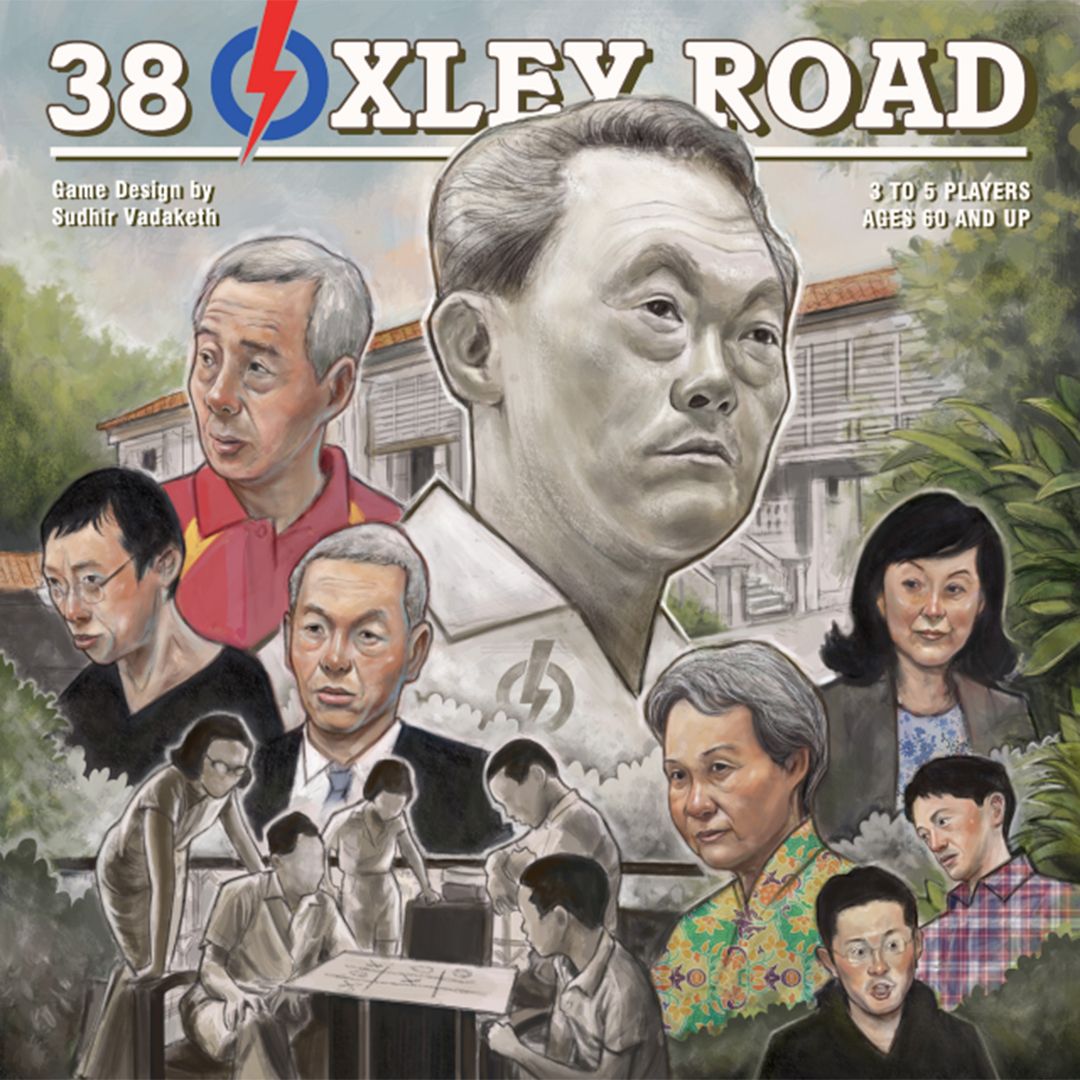

Like others, I appreciate aspects of Elizabeth’s life—and love Claire Foy in “The Crown”—though Kunzru’s searing statement is never far from my mind. Are we still in awe of hierarchy and empire? It’s easy to criticise Malaysia and Thailand, but to be fair there are shades of all this in the cult of Lee Kuan Yew. If Singapore turns his old house into a shrine and if any of his grandchildren enter politics, some might accuse us of monarchy behind the mask of meritocracy.

At Jom’s first-ever, behind-the-scenes Zoom call with our journalists, Waye, our co-founder, and I will have a conversation about 38 Oxley Road. I’ll share stuff that I couldn’t publish in the e-book, The battle over Lee Kuan Yew’s last will.

- What sorts of roadblocks did I encounter as I tried to research and write about the Lees?

- Which bits of the draft did lawyers want to remove?

- What does the 38 Oxley Road bungalow look like on the inside?

This, and more, at 8pm SGT on September 27th. Save the date!

Jom’s behind-the-scenes calls with journalists are exclusively for our “Supporters” and “Patrons”. We will be e-mailing you directly with details.

Note: Jom has three levels of membership: Member (S$10/month); Supporter (S$25/month) and Patron (S$950/year).

Subscribe today to join us. And for “Members” eager to join, you can upgrade to “Supporter” or “Patron” under the “Account” option on our website.

I’d like to end with Amandas, who for the past six months has been delighting and scaring me with her efforts to enter Ukraine. Delighting me because I’m jealous! The reporter in me wishes I was on the ground there, observing, chatting, sharing the stories of the voiceless. In many ways it is journalism’s highest calling.

But she’s also scared me on a few occasions, once telling me that she’s on her way back to London, as long as the area she’s in doesn’t get shelled. Sitting at home in Pasir Ris with a beer in my hand, I wasn’t quite sure what to feel.

Amandas had been sent there to report for Al Jazeera. I’m glad she has found time to write a postcard for Jom. We hope to slowly attract a diverse group of overseas Singaporean writers who can send us postcards from their little corner of the world. If there’s somebody you as a reader would like to hear from, reply and let us know! We’ll add them to our list.

We can always learn something from Singaporeans abroad. The ending of Amandas’s postcard, about the Ukrainian search for belonging and identity, has lessons, I think, for “commoners” and monarchs everywhere.

Best wishes,

Sudhir Vadaketh

Editor-in-chief, Jom

If you've enjoyed our newsletter, please scroll to the bottom of this page to sign up to receive them direct in your inbox.