Dear reader,

This week, Jom has a new social media manager. Taahira Ayoob has replaced Fiachra Ross, who’s left for his Masters. In other words, a brown woman has replaced a white guy.

Hang on. Why even mention skin colour and gender? It makes me uncomfortable to look at people through the identities they wear. And yet, as we’ve built the Jom team over the past year, Charmaine, Waye and I, Jom’s co-founders, have realised that in any modern organisation, it’s important to do so. If not, diversity suffers, and in the process so does your team and product.

I want to take you back to November 2021, when Jom was hiring our first employee, a head of research. There were three Chinese and one Indian on our shortlist. Waye asked if we should give extra weight to the Indian candidate.

I was a bit taken aback. We have two women and one Indian among our co-founders—we’re already pretty diverse.

Surely we should be hiring purely on merit. The problem is that “merit” itself is a contested topic. How do we measure it? It could be based on experience, skillset to perform the job, or even that old Singaporean favourite, your PSLE exam results (taken when one is 12).

In each of these domains, merit can be used to mask underlying power structures or privilege—ultimately perpetuating it under the guise of fairness.

By citing “merit” as a reason there is a potential implication that the different candidates had equal opportunities to become meritorious or prove their worth. Which we know is not the case.

Consider that for years the ruling People’s Action Party has said that Singaporeans are not ready for a non-Chinese prime minister. But recently Lawrence Wong, presumed next prime minister, said that “we choose our leaders on the basis of merit.”

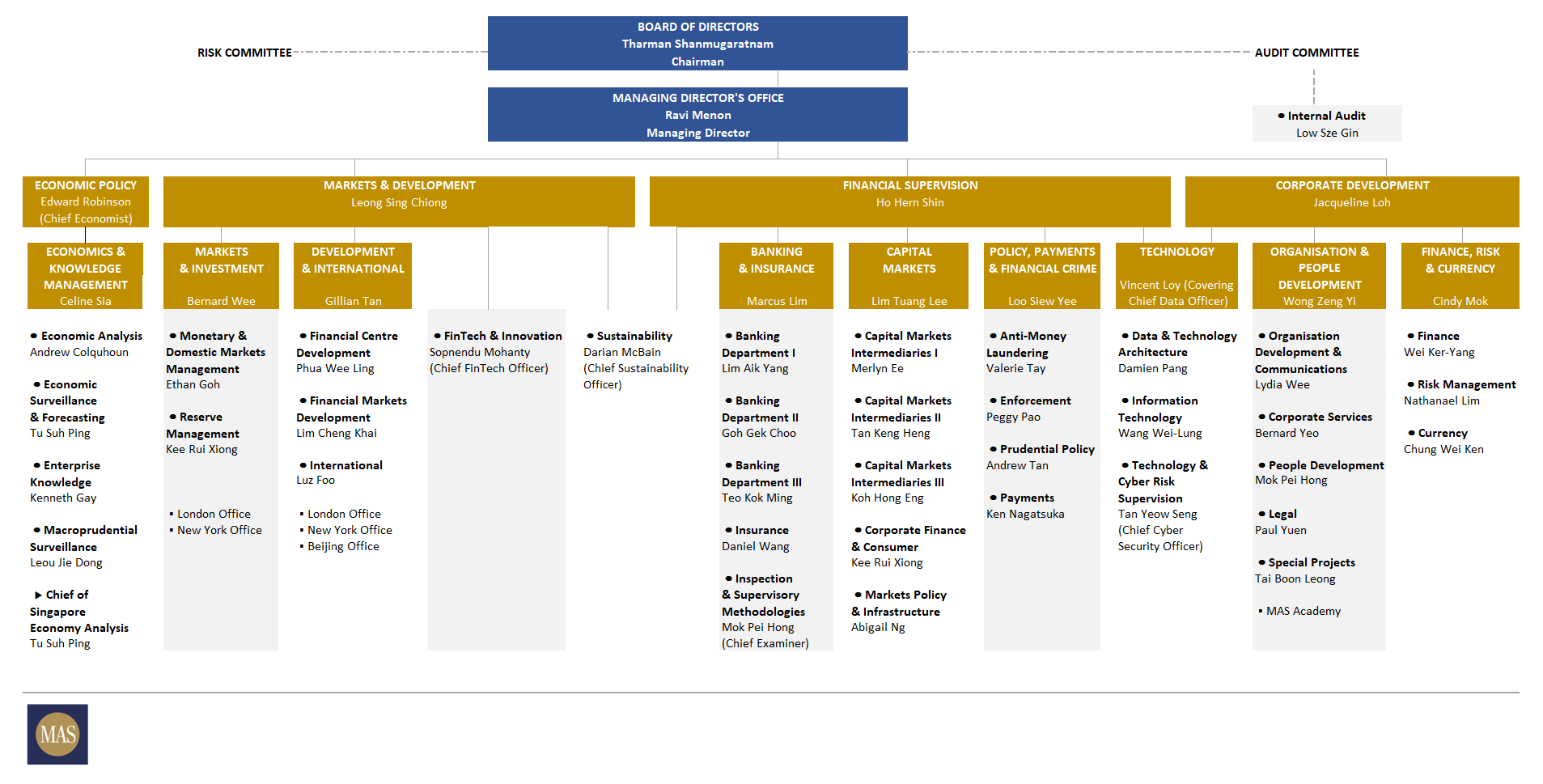

Sorry, Tharman. “Merit” has been wielded against you. There can be no other complaint.

And it’s not simply that the dominant socio-economic group–Chinese, in Singapore–could more easily than others access those indicators of merit. Worse, the indicators could be sending the wrong signal. Maybe the person with all the brand name schools on their CV isn’t particularly suited to the role or our company.

All that is not to imply that we ditch the concept of “merit”. Rather, we need to ensure that candidates from different backgrounds are given the opportunity to demonstrate their merit, which may take different forms, and may be applicable to the role in different ways.

I started to think more about this after we put out our first call for journalist contributors last year. I had mentioned that anybody with “published work” should write in. Lots of people did, but after a few months, I noticed a worrying pattern.

We had a lot more Chinese candidates (relative to the overall population). With a couple of minority candidates, as soon as I asked for their publication history, the line went dead. Most Chinese, by contrast, were able to instantly flood me with their CVs, their published work, sometimes even their ancestral histories and obscure connections to one of the co-founders at Jom.

This is particularly relevant for media firms in a multicultural society like Singapore. If your outlet is dominated by Chinese, you deprive yourself of many things, including intellectual diversity and the ability to write with empathy and insight about minority groups.

I wondered about the difference. Since one needs leverage and networks to get published, did I make a mistake asking for published work? Maybe I should have asked just for a writing sample? Is it because minority candidates have fewer mentors and role models in their field, and thus find it harder to pull together a CV? Has my own socio-economic privilege blinded me to the challenges other minorities face in the hiring process?

Quite possibly, for each. From this came perhaps the most important organisational diversity lesson for us: ensure that job descriptions, job ads, and any other corporate marketing do not unintentionally deter minority candidates, whether they be ethnic minorities, persons with disabilities, or any other group.

I’ve discussed diversity with friends working in San Francisco and Toronto, places where “DEI” (diversity, equity and inclusion) is tattooed on managers’ foreheads. Each of those letters is important. I find in Singapore organisations are often content striving for D, without the E and the I.

In any case, while some of my friends’ initiatives might strike Singaporeans as wonky, the aforementioned mantra is something, I believe, we can all agree on, and do better at. In a multicultural, meritocratic society, people from different cultures must work their way through hiring processes. Too many candidates from the dominant group, and perhaps the approach and messaging is off.

The other thing we take seriously at Jom is the way we project our diversity and representation. It’s not enough, we’ve realised, simply to believe in these tenets. The optics matter too.

After we hired Jean Hew as our head of research, I started to ask some close friends, “So, three Chinese women and one Indian guy—do you think we are diverse?”

What a range of responses. Some said we are super diverse, since all four of our core team come from a minority or disadvantaged group. This school of thought generally believes that anybody but a straight Chinese male checks a diversity box. It’s not dissimilar to the “anybody but a straight White guy” theory of diversity in the West.

At the other end some said that we’re not diverse at all, since three out of four Chinese simply mimics Singapore’s ethnic ratio. “If you had more brown people I’d say you’re ‘diverse’.”

My wife, perhaps scarred by 14 years of marriage, had the pithiest answer: “How can you be ‘diverse’ when the boss is a man?”

A buddy in Toronto, a founder herself, told me something salient for any organisation, but particularly really small ones. You don’t want the optics of the organisation to scare off groups not represented. It will make it harder and harder for you to achieve diversity.

In other words, three Chinese in the team is probably fine for now, but what if our next three hires are also Chinese women? If people look at Jom and see one Indian guy and six Chinese women, what will they think? (Answer: another Books Actually.)

Jokes aside, the serious question for me was: would a brown woman be willing to join an organisation completely over-represented by Chinese women?

I asked several brown women in Singapore and their response was fairly consistent: they’d think twice. It was often flecked with caution and humility. “Could just be me, I don’t want to project my own experiences and vulnerabilities onto others,” one told me.

Anyhow, when Charmaine, Jean, Waye and I had our first serious chat about diversity, we decided not to think too much about it for now, but that there would come a point when we had to actively diversify.

As luck would have it, great minority candidates emerged organically. Fiachra joined in May, around the same time as Faris Joraimi, Jom’s history editor.

And now, this week, we are delighted to have our very first brown woman at Jom. I prefer to think of her just as Taahira, but I’ve grown to accept the discomfort of recognising people’s groups and identities.

Without doing so, there’s no way we can really understand each other’s backgrounds and lived experiences, let alone begin to address the deep, systemic inequalities that exist in every society.

We share our thoughts on diversity and values so that you, as a subscriber, also know the philosophies you're supporting. For those who have yet to, get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

This week, we have a new essay by Abhishek Mehrotra, an Indian writer and researcher, which examines some of Singapore’s roads that have been named after notorious colonial figures. Who knew that Havelock, Neil and Outram roads mask such horrific legacies? Fascinating stuff.

And in our usual Singapore This Week, we talk about the state visit to Singapore by Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr, our city-state’s journey to net zero, as well as a new initiative aimed at inclusiveness and academic egalitarianism for students at polytechnics and ITEs—yes, one way to address the ills of “meritocracy”.

Best wishes,

Sudhir Vadaketh

Editor-in-chief, Jom

Some further reading

A lot of the good diversity stuff I’ve read recently has come from the McKinsey Global Institute, although of course we have to calibrate insights for Singapore—our issues are quite different from the US’s.

“Workplace diversity programmes often fail, or backfire” is an interesting, recent graphical piece by The Economist, which really proves to me that we’re in the very early stages of dealing with these issues.

On meritocracy, many of Michael Sandel’s critiques can, I think, apply to Singapore. Read an excerpt from his book.

If you've enjoyed our newsletter, please scroll to the bottom of this page to sign up to receive them direct in your inbox.