Society: Where real power resides

While many Singaporeans struggled to make ends meet last year, Marina Bay Sands (MBS) saw record profits of US$2bn (S$2.7bn). This is thanks to its post-pandemic strategy of targeting the ultra-rich: fewer rooms, more high-end suites, more “butlers”. An average daily room rate of S$950, and suites ranging from S$1,300-S$35,000 per night, haven’t deterred the global elite, leading to an astonishing 95 percent occupancy rate. And it’s hungry for more. This week saw the groundbreaking ceremony on its adjacent US$8bn (S$10.3bn) “ultra-luxurious resort and entertainment destination”. This one won’t even have any rooms. Just 570 suites. “Marina Bay Sands is obviously very premium, very luxury—but this will be a level higher,” Paul Town, chief operating officer, said last year. In a Facebook post about the ceremony, Lawrence Wong, prime minister, mentioned plans for kayaking and dragon-boating nearby. “We’re writing the next chapter for Marina Bay and making an even more vibrant and inclusive destination for all to enjoy!” One wonders if ChatGPLarry is programmed to drop “inclusive” into every speech.

Wong was at the centre of nine luminaries on stage, each holding a shovel. Next to him was Miriam Adelson, the 79-year-old billionaire who co-founded Las Vegas Sands, the owner of MBS, with late husband Sheldon. The Adelsons have long funnelled their money towards controversial, right-wing Zionist causes: launching Israel Hayom, where she’s publisher, and which shortly after October 7th 2023, called for the “voluntary migration” of Palestinians so they wouldn’t raise “another Nazi generation”; and the Macabee Task Force, which harangues Israel’s critics in the US, most recently Columbia University and Mahmoud Khalil, its graduate student who just emerged from months in detention. Miriam Adelson has long been one of Donald Trump’s biggest donors, and according to a New York Times investigation, is firmly against a two-state solution and may want Trump to push for annexation of the West Bank.

Sure, a free society should respect her right to spend her money as she wishes. But isn’t it odd that Wong rails against tariffs and the persecution of Palestinians but then facilitates profits from Singapore that might fund those very things? Can a sovereign state’s investment policies ever properly align with its foreign policy goals? Or is this simply the fate of a free-market global city, where amoral capital must be allowed to move in and out? A day after the groundbreaking ceremony, Halimah Yacob, former president, condemned the “continuing carnage” in Gaza. Amidst the gushing over the expansion of our capitalist temple on the bay, her voice was lost.

Society: As it turns 180, The Straits Times ponders its future

How constrained is The Straits Times (ST) in its local coverage? Does its current offering position it for success in today’s tempestuous media industry? Singaporeans have been discussing these issues since July 3rd, when Cheong Yip Seng, ST’s former editor, launched Ink and Influence: An OB Markers Sequel, a follow-up to his 2013 memoir. He argued that ST should pivot away from local news to regional and international commentary, particularly in geopolitics. This would allow it to better compete for global English-language readers, who’re possibly tired of the “bias” and “blatant hypocrisy” he sees in the Western media—citing their Palestine and Ukraine coverage as examples.

“I think Cheong was thinking about ST 20 years ago which had excellent foreign coverage with an extensive network of bureaus. Not so sure about now,” said Bertha Henson, a commentator who previously worked under Cheong at ST. “What was amazing for me at the launch was how the former editor-in-chief was full of praise for CNA, saying it was a better product than ST.” At the launch, Cheong cited a Reuters survey that ranked CNA and even Mothership, barely 10 years old, as more widely read than ST.

If ST journos’ spirits were flagging, Wong came to the rescue. At the paper’s 180th birthday celebrations this week, the prime minister cleverly referenced a different point from the same survey: showing ST as the most trusted media brand here. Other puzzling platitudes included his opening. “Not many organisations endure for 180 years—let alone in the fast-changing media world. That The Straits Times has done so speaks volumes about its relevance, its resilience, and its remarkable ability to evolve.” Actually, it speaks volumes about the power of public bailouts. Wong also said, “We do not want our national newspaper to be owned by billionaires with narrow or partisan agendas.” But that’s precisely how many here view ST: effectively “owned” by its political paymasters.

At the recent GE, there were some obvious indications of ST’s bias, including the abysmal reporting of the open letter by Tan Suee Chieh, Income’s former president, criticising politicians’ roles in the Allianz-Income debacle. (What would have probably made front-page news in most democracies.) Those aside, ST’s coverage was decent, including with its video content. As Jom reported last week, it’s now offering platforms even to unelected opposition parties. If Wong wants the publication to thrive, he should decisively remove the spectre of executive interference, and encourage fair criticism of all policies and parties. Let ST’s journos utilise the breadth of their talents in analysis and commentary. Ensure no editor has to ever again whisper “OB markers”.

Society: Schooling change

Qualitative research from EveryChild.sg, the NGO crusading for primary school education reform, has confirmed what has long been suspected: the suffocating pressure of the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) at such an early age squeezes childhood of joy, spikes anxiety levels, and inflicts intergenerational trauma on many. Meanwhile, its emphasis on results-obsessed learning robs many students of the interests that once animated them.

The report’s authors interviewed 15 mental health professionals who work with young children. One was shocked at how some of their 10-year-old clients had schedules “more intense than mine as a working adult”, with packed days of tuition, school and homework starting at 6am and ending at 11pm. Other experts detailed how quickly the pressure takes hold. “I had a rash of [Primary 2] kids that…were doing intense biting of finger[s] and toenail[s]…to the point where there was bleeding” out of fear of not finishing their homework. Some poor performers bullied other students to vent their frustrations; depressingly, even the better performers dealt with the overwhelming pressure by doing the same thing. Even without visible symptoms, chronic stress on developing brains can lead to poor self-esteem, risk-avoidance and an inability to stand criticism, which can carry on into adulthood. Interviewees spoke of adult patients who place themselves in an imagined social hierarchy based on their PSLE scores from years ago.

All actors are responding rationally to its inherent incentives, the report emphasises. Students have internalised the relationship between “top schools” and social status; teachers push for higher scores as part of their Key Performance Indicators (KPIs); parents are informed by their own traumatic experiences and fearful of foreclosing future opportunities for their children in the PSLE’s “stack-ranking” structure; and tuition centres, oft castigated, are merely reacting to the commercial incentives created by the singular focus on academics.

Intriguingly, the report estimates that expat students at international schools receive mental health counselling for academic anxiety at half the rate of local peers. One expert claimed they could “almost predict” that while local clients will focus on academics, international ones will more likely be worried about some social situation. Said another: “In the international schools… academic stress is just one area. They can find joy in other areas.” The authors don’t romanticise international schools. Yet, they wonder if this indicates that far from being inevitable, the stress experienced by local children was brought about by a particular confluence of time, place, policies, and attitudes that could yet be changed.

Society: Banking on cryopreservation insufficient to conserve endangered wildlife

Imagine a zoo of the future filled not with live animals but extinct ones: exhibits of cells, tissue, blood products, reproductive material and DNA samples. These cryptic cabinets of curiosities will house cryogenically frozen pieces, like a genetic puzzle of an animal kingdom long lost. A dystopian future perhaps, but increasingly plausible given the rate of habitat destruction, climate change, overexploitation and pollution. Driven by human activity, experts believe that we are in the sixth mass extinction. (The last one occurred 65.5m years ago.) A 2019 UN Report found that around 1m animal and plant species are threatened with extinction, many within decades, more than ever before in human history. According to the WWF Living Planet Report 2022, there has been a 69 percent average decline in wildlife populations since 1970.

There is a potential solution, however. Cryo-conservation is seen as a promising strategy to preserve genetic material for recovering species and preventing extinctions in the distant future. Singapore is doing its part to build a “frozen zoo” of South-east Asian animals, including endangered mammals, birds, amphibians and reptiles. Two repositories at the NUS Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum and Mandai Wildlife Reserve have biobanked samples from some 3,283 species at sub-zero temperatures. When thawed, the tissues and cells are used mainly for research, but can also be reanimated to solve wildlife crime like illegal trafficking, and for novel techniques like in-vitro fertilisation.

Science fiction, though, has become reality in much larger, more established wildlife-based biobanks in other parts of the world. In the US, the 50-year-old San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Frozen Zoo, holds what is reportedly the world’s oldest, largest and most diverse repository of living cell cultures and reproductive cells from wildlife, including three extinct species. In 2020, it cloned a black-footed ferret using cryopreserved DNA—the first endangered species to be cloned in America. Three years later, it cloned two critically endangered Przewalski’s wild horses, which returned valuable generic diversity to the living population. Biotechnology has come a long way since Dolly, the cloned sheep, was born in 1996. Much debate around its ethical use has ensued, including cloning for genetic rescue, and biobanking for wildlife conservation. Aside from the welfare of animals, these include concerns around consent and use. While cryobanks play a crucial role in shaping the future of our planet’s biodiversity, the buck must stop with us.

History weekly by Faris Joraimi

In a sterile archive room, a puppet from the north-eastern coast of Malaya is taken out of its box, and held up before a makeshift screen. It casts shadows, for the first time in over a hundred years. The puppet, made by Tok Dalang Che’ Abas, is part of an extensive collection of materials gathered from the expeditions of Walter William Skeat, British ethnographer, in the Malay Peninsula. Housed at the University of Cambridge since 1899, the collection of textiles, weapons, ritual objects, puppets, and documents was opened for the first time early this year. The project, called “Unboxing Skeat: Decoloniality, Memory, Knowledge,” is led by Iza Hussein, historian at Cambridge’s Pembroke College. Based on the website of “Unboxing Skeat”, the colonial context of these objects’ amassement is placed front and centre for critique. “How does the colonial history of Malaya and Siam provide a new vantage point for raising decolonial perspectives and developing methods for research, access, and collaboration?” it asks, connecting the artefacts and their histories to questions about the way knowledge is produced in universities, and resonances between “Southeast Asia and the global South”.

In the 1890s, Skeat sought data on the lifeways and practices of places not yet transformed by European influence. Formal colonial rule was not yet established throughout the Malay Peninsula, with some kingdoms remaining either autonomous or under Siamese suzerainty. What reformist bureaucrats would later call “superstition” remained widespread features of everyday economic life: pawangs (ritual specialists) helped locate the mineral and forest resources destined for global export, and farmers still propitiated rice spirits. Traditional entertainments such as the shadow-puppet theatre still gathered crowds in villages.

Stationed as an officer of the colonial government in Selangor, Skeat gathered meticulous information on coastal Malays and interior Indigenous groups. His findings became the subject of Malay Magic (1900), now considered a classic work on the religion of Malaya, though it’s marred by colonial judgements about the “primitive” and “unscientific” character of local peoples and cultures. From 1899-1900, Skeat led a Cambridge University expedition in Kelantan and Terengganu, which resulted in his second major work, Pagan Races of the Malay Peninsula (1906). While Skeat’s words have cast long shadows, the objects he collected have not. The overdue unboxing may help to reconnect them to the world they left behind, and in some small way, reconstitute it in the present.

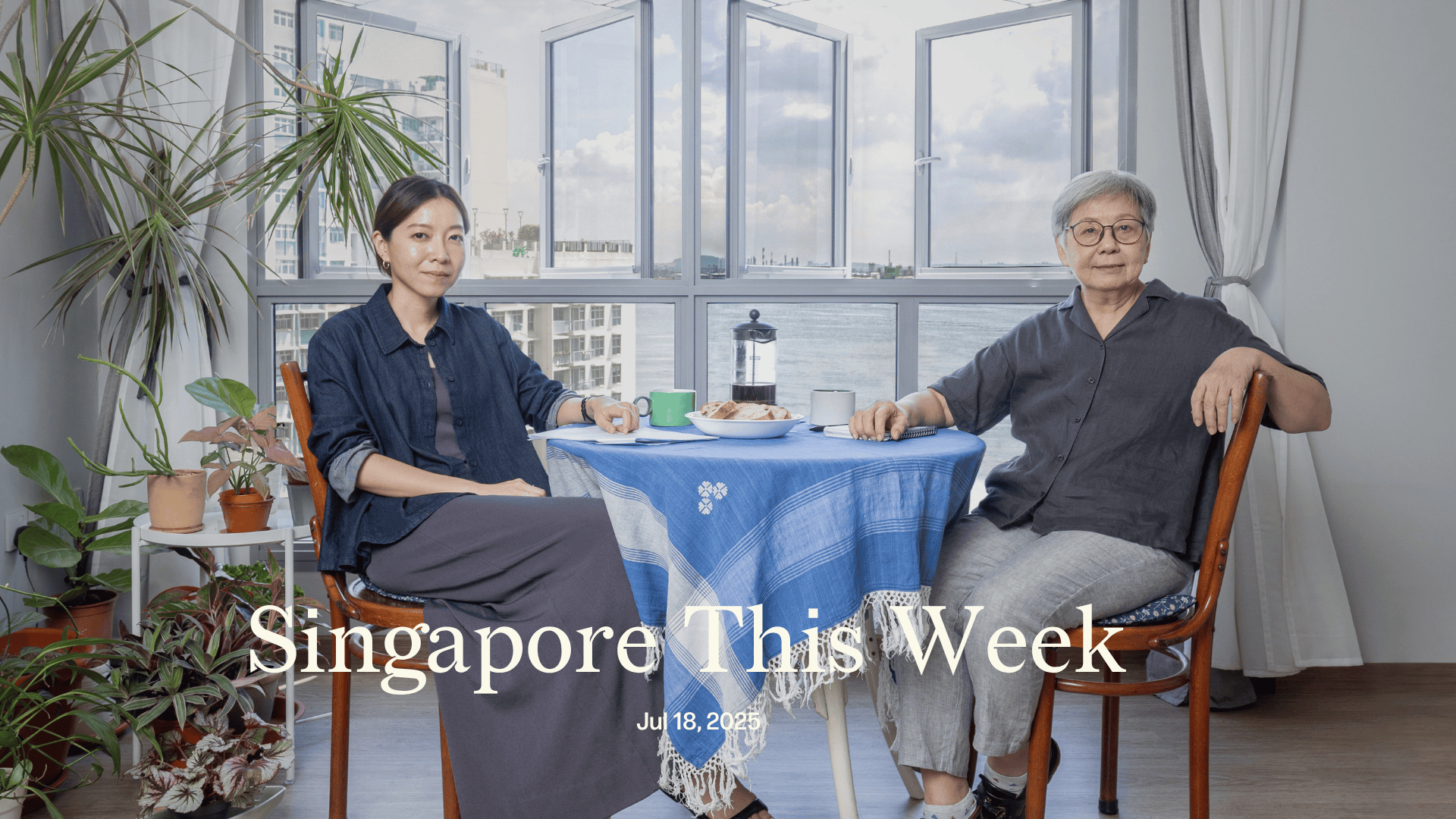

Arts: Let’s walk to Venice

It was quite the sight. Amanda Heng—a high-heeled shoe clamped between her teeth, a small circular mirror clasped in her hands—walking barefoot and backwards outside the former LASALLE College of the Arts campus on Goodman Road. This was 1999, and the tax officer-turned-artist was joined by a small procession of five other women, each with shoe in mouth and mirror in hand. “Let’s Walk” was a response to the rapid retrenchment of women during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and how many resorted to amplifying their physical attractiveness through plastic surgery and beauty products in an effort to keep their jobs. The work has since travelled the globe, from Indonesia to Sweden. The pioneering performance artist and Cultural Medallion recipient was making strides in a time where her chosen artform had a murky reputation in Singapore, stripped of funding and frequently misunderstood. That didn’t stop her from building a body of work that’s participatory and collaborative, attentive to gender politics and social identities. “Let’s” is a popular invocation in Heng’s work, as are everyday acts of walking, speaking and touching. In “Let’s Chat” (1996), for instance, she invites members of the public to sip tea and pluck taugeh around a table with her, and it’s since been presented at both shopping malls and markets.

Now 73, Heng is getting one of her largest stages yet. She’s the country’s pick for the Singapore Pavilion at the Venice Biennale next year, one of the most prestigious and longest-running exhibitions of contemporary art. She’s also the most senior artist and only the second woman to grace our pavilion. The upcoming Biennale will feature artists from over 75 countries in its main exhibition space and some 30 national pavilions speckling the picturesque city. Selene Yap will be curating Heng’s presentation at our assigned 250 sq m space in a cluster of 16th-century army barracks. The histories of these permanent pavilions can be traced back to 19th-century political posturing—which foreign country gets a brick-and-mortar platform in a lush garden, and which doesn’t—with curatorial decisions largely left to the caprices of each country. This means they’ve long been a funhouse reflection of contemporaneous geopolitics. Russia’s contingent of artists decided to withdraw in 2022 after their country invaded Ukraine; the Russians have since left their empty, ample pavilion to the Bolivians. In the previous edition, artists and cultural workers called for a boycott of the Israeli pavilion, which was then sealed off by artist Ruth Patir and her curators, who wrote on a sign taped to its glass door that they would open the exhibition “when a cease-fire and hostage release agreement is reached”. The pavilion never opened. And fewer commissioning processes have been as plot twisty as Australia’s. Creative Australia first sought the Lebanese-born artist Khaled Sabsabi for next year’s edition, then dropped him over his 2007 film “You”, which features a speech by a Hezbollah leader. Following a period of political dithering and public protest, the arts council backpedalled and recently reinstated him. Maybe Heng’s brand of intimate and convivial intervention is just what a defensive, polarised Biennale needs. Jom jalan.

Arts: Fringe benefits

Last year, telco M1 shocked the Singapore Fringe Festival team when it decided to end its 21-year sponsorship of the festival. This year, the festival had a much more pleasant surprise. Its crowdfunding campaign to keep the Fringe going has exceeded its initial S$50,000 target. The S$50,519 raised means that it’s a go-ahead for next year’s edition in January. The annual festival is organised by local theatre company The Necessary Stage (TNS), known as much for its socially engaged work as its interdisciplinary approach to creating performance. Melissa Lim, TNS’s general manager, told ST that it’s hoping to keep the festival at the same scale as recent editions. One costs about S$230,000 to put up (with M1 previously contributing S$100,000), and usually features between six to seven shows from Singapore and around the world. The organisers will be relying much more heavily on ticket sales this year to recoup costs, and are still on the lookout for partners and sponsors to keep the Fringe going.

The Fringe remains a special site for emerging artists and experimental forms, as well as adventurous audiences with an appetite for creative risk at affordable prices. It’s been through several evolutionary phases, from earlier themed editions such as “Art & the People” or “Art & War”, to others paying homage to performance art stalwarts like Suzann Victor and Amanda Heng. Former festival artistic director Sean Tobin had the entire 2018 edition dedicated to Heng’s seminal work, “Let’s Walk”. “[W]e feel the need to dispel the myth that Singapore’s art scene is still very young, safe and clean,” said Tobin at that year’s festival launch, “and with Amanda’s work, [we] create a reflection on our own arts heritage as these young artists respond to it with their own pieces.” Private sponsorship, according to Fringe artists, has protected the edgy festival’s autonomy in a constrained political landscape where art is often subject to censure or censorship. Loo Zihan, whose work exploring Singaporean queer histories has headlined several Fringe editions, lauded its “sustained form of pragmatic resistance that is essential to a vibrant and healthy arts ecosystem”. The artist-researcher told Jom: “In a landscape where artistic expression is often met with hesitation, the fringe festival has provided a rare space where my work can thrive.”

Tech: Grabbing autonomous shuttles and new jobs

As autonomous vehicles (AVs) loom closer to reality in Singapore and job concerns flare up in the local population, Grab’s pilot with South Korean vehicle tech firm A2Z attempts to build a framework for sustainable implementation. The fixed-route shuttle between Grab’s one-north headquarters and the MRT station is typical of Singapore’s approach to new tech: controlled environments first, then gradual expansion. With 11 sensors including LiDAR, which measures distances and generates three-dimensional maps of natural and built environments, creating 360-degree awareness, the service is as much about collecting data as moving passengers. This data will help refine algorithms that will hopefully keep passengers and pedestrians safe on Singapore’s newly-opened 1,000km of AV-testing roads.

The masterstroke? Grab’s decision to train its ride-hail drivers as safety operators. This addresses the job displacement elephant in the room, at least in the short-term. As Singapore’s AV market prepares to triple to US$2.17bn (S$2.79bn) by 2032, such pilots serve dual purposes: solving last-mile connectivity gaps in suburbs like Punggol, where national AV shuttles will launch later this year, and normalising autonomous tech in small steps rather than vaulting straight to flashy robotaxis, as is the case with Waymos in America.

Yet, challenges lurk beneath the driverless sheen. The shuttle’s success hinges on Singaporeans embracing driverless transport, not a small feat in a nation where demands for public transport quality are high and where recent comments by Jeffrey Siow, minister for transport, on allocating COEs to private-hire vehicles (such as Grab) sparked outcry. And while Grab positions this as mobility’s future, profitability remains uncertain given high sensor costs and niche routes.

Tech: No more poking for SIM card

Remember when you’d have to find a pin to swap out the SIM card in your phone when you landed in another country? Now with eSIMs that can be loaded simply by scanning QR codes, travellers have one less thing to fret about. And they can burnish their green credentials too: the carbon footprint of eSIMs is 46 percent smaller than plastic cards.

Leading the charge in the eSIM race in Asia is Singapore’s Airalo. The company has cracked the code on turning eSIMs from niche tech to mainstream essential, securing its unicorn crown with a US$220m (S$283m) funding round that values the firm at over US$1bn (S$1.29bn). It is a significant moment for the once-obscure technology that spent a decade in the wilderness before Apple’s 2018 iPhone integration sparked mass adoption. Airalo’s 20m users across 200 countries prove travelers will ditch plastic SIMs when given seamless alternatives. This shift threatens the global roaming market that telecom giants once dominated.

The company’s timing couldn’t be sharper. With global eSIM connections expected to touch 4.5bn by 2030, and Apple going SIM-less in iPhones, Airalo rides a perfect storm of tech readiness and consumer behavior change. Its capital will fund hyper-localised data packages and B2B solutions, but the real innovation lies in its asset-light model that does not require costly spectrum licenses or intensive retail distribution—just pure software margins.

But telecom operators are waking up to the threat, with Vodafone and Deutsche Telekom now launching rival eSIM marketplaces. Airalo’s valuation assumes it can own the travel segment before mobile carriers and phone manufacturers reclaim the space. For now though, this unicorn’s success proves even stodgy industries like telecom can be unbundled, one digital SIM at a time.

Faris Joraimi, Abhishek Mehrotra, Corrie Tan, Tsen-Waye Tay and Sudhir Vadaketh wrote this week’s edition. Additional contributions by Liyana Batrisyia and Sakinah Safiee.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.