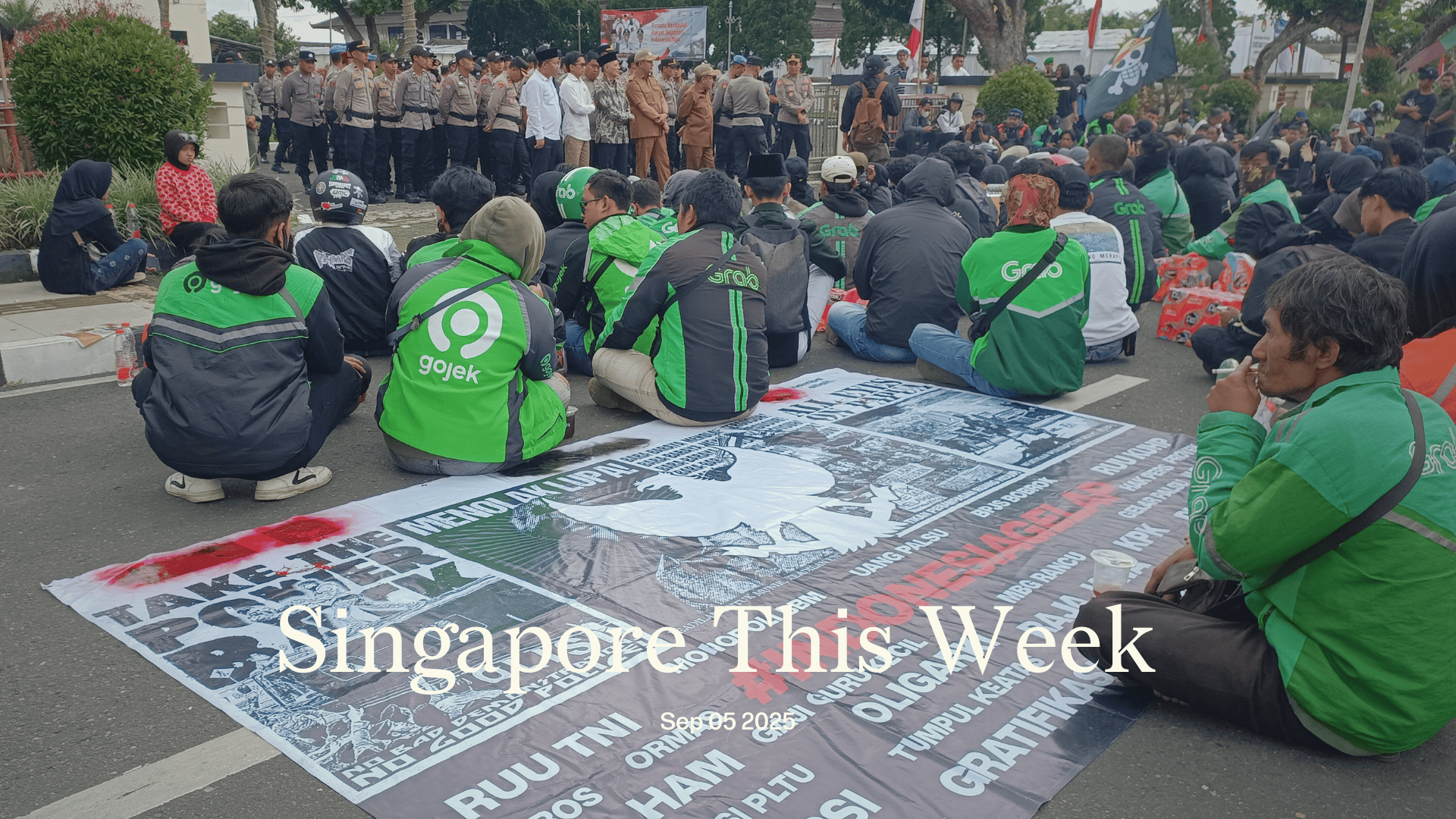

International: In solidarity with Indonesians

Indonesia is resisting. Labour unions, student activists and women’s groups are among those protesting political excess—the most egregious was a proposed US$3,000 (S$3,861) monthly housing allowance for legislators. In Jakarta, the minimum wage is just over a tenth that. Many on minimum wage work for Gojek, part of the huge “ojol” (Gojek online) army of ride-share bike drivers. One of them, 21-year-old Affan Kurniawan, was making a delivery when a Brimob (Mobile Brigade Corps) vehicle clearing protestors ran him over. Ojol are the “eyes and ears in every single community in the entire country…[T]he intel gathered and capacity to organise is unlike any other labour group I've ever seen,” wrote a longtime Indonesia observer. A video of Affan’s death fanned the fiery protests into an inferno. Provocateurs may be responsible for the burning of two regional-parliament buildings and looting of five Jakarta officials’ homes. Perhaps 10 have now died across the country. Prabowo Subianto, elected president last year, moved swiftly. While pledging to quell violence, he rolled back the legislators’ perks and promised to hold those responsible for Affan’s death accountable.

Still, the protests continue. It’s an indication perhaps that the unrest has deeper roots. The Indonesian middle-class has shrunk by 16 percent since 2019. In its maiden budget earlier this year, the Prabowo government increased national social spending but slashed contributions to states, forcing them to raise local taxes. The Trump tariffs—19 percent on Indonesian exports—have deepened economic uncertainty. During such times, lavish perks do not for a convivial polity make. There’s a sense of disaffection with Prabowo’s mega-coalition, which includes almost all parties, and has dulled parliamentary contestation. But, in Indonesia, at least some power resides with the people and the unions.

Amidst the fear, the anger and the deaths, the one bright spot has been the support and solidarity extended towards gig workers, often through social media platforms. Instructions for Grab customers across South-east Asia to send food to Indonesian riders have gone viral. Gojek subsequently launched its own “treat your driver” feature. The precarity of gig work, and seeping unease about the rising cost of living, set against a global order unravelling seemingly in slow motion, is opening doors for cross-border camaraderie that transcends stodgy summits. Something to cheer, even as we contend with the risk of something worse.

Prabowo, a former army general, has sent troops into Jakarta and linked protests with attempted treason, prompting worries about a return to martial law. The editors of The Jakarta Post referenced an attempted attack by an unspecified mob on a residential complex with large numbers of ethnic Chinese, “a little over two months since the 27th anniversary of the May 1998 tragedy.” Prabowo, they said, “has already undermined civilian supremacy by appointing more TNI [military] officers to positions in the government and at state-owned enterprises. A military government is the last thing the greater public wants from his administration.”

Politics: Fear and loathing in Bukit Gombak

Shortly before he wrote Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, a rumination on the failures of the 1960s counterculture movement in the US, Hunter S Thompson in 1970 ran for sheriff in Pitkin County, Colorado. The incumbent had been cracking down on “freaks”, including stoned hippies who’d fled there. Intent on changing the system from the inside, Thompson ran on a third-party “Freak power” ticket. For his troubles, depicted in “Freak Power: The Ballot or the Bomb”, he and his supporters faced surveillance and intimidation, including death threats. A portrayal of more recent US grassroots brawling is “Street Fight”, which followed Cory Booker—now a senator with a record-busting marathon speech—on his failed 2002 mayoral bid in Newark, New Jersey. Campaign posters destroyed; government supporters demoted; businesses shuttered before they could host fundraisers; and volunteers intimidated.

Singapore’s placid, precious political environment may lull one into thinking this will never happen here. But opposition party members and volunteers have long complained about harassment from mysterious people in the course of their public work: followed through HDB corridors, pamphlets collected and shredded, cameras stuck in their faces. This past January offered concrete evidence. Just months before GE2025, Stella Stan Lee, a volunteer with the Progress Singapore Party (PSP), was stuck with a colleague in an HDB elevator, as two men filmed them, their smartphone-carrying gangly hands swooshing around the confined space, like some Orwellian Lion Dance. She filed a police report, as part of a broader party complaint about volunteers from the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP). (The disturbing video of two incidents is worth watching.) Low Yen Ling, a senior minister of state and incumbent—her district now carved out of a larger one—accused the PSP’s volunteers of being hostile, including slapping a PAP volunteer’s face twice. “We look forward to a full police investigation, and for the whole truth to become public. That way, the public can know what actually happened.”

Too bad, Low. Last Friday the PSP confirmed that the police had concluded its investigations, and in consultation with the Attorney-General’s Chambers, assessed that no criminal offence had occurred—and that no statement would be issued. Who were those men? We’re none the wiser. The lack of transparency and accountability about alleged harassment, stalking and slapping may embolden others to do the same. The opacity does the PAP no favours; cynics will suspect that the findings were buried because they’re unfavourable to it. “Unfortunately, I proved what I set out to prove…that the American Dream really is fucked,” Thompson had said after his defeat in Colorado. The disenchanted here who feel similar will add Bukit Gombak to a long list.

Politics: Status quo

“We’re not a two-party system. We’re a one-and-a-half party system,” Pritam Singh, Workers’ Party (WP) chief, said on a recent podcast. Headline results of the latest post-election survey by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), a government-adjacent thinktank within NUS, suggests that this unique system may persist for a while yet. Even as older Singaporeans (40 and over) seem to be getting more pluralist in their outlook, younger voters (20-39) appear to be getting more conservative and comfortable with the status quo, perhaps driven by materialist concerns, said IPS. (As in other surveys, “Cost of living” was a hugely important issue for respondents.) Still, for the first time since the survey began in 2006, the PAP and the WP are neck-to-neck in terms of credibility, with mean scores of 3.9. Meanwhile, just 12 percent of respondents disagreed with the notion that the outcome of GE2025 was good for Singapore. (Some 57 percent agreed and another 24 percent were neutral.)

That said, other findings suggest that “one-and-a-half” isn’t a foregone conclusion. For one, the Singapore Democratic Party is now at its highest credibility score, 3.3, pipping the PSP, which dropped from 3.5 in 2020 to 3.2 now. A smaller segment than ever before agrees that “the election system is fair” and that “there is no need to change” it—suggesting that the numerous agitations for electoral reform are having an impact. And when asked a new question, “I would prefer if there is a change in the party that governs Singapore every now and then,” 39 percent agreed, 30 percent were neutral, and just 24 percent disagreed.

Yet less than 35 percent actually voted for the opposition. Perhaps, as Walid Abdullah, an associate professor at NTU, noted in relation to Jom’s own survey, it’s just a bit of bravado, stemming from what’s known as personal desirability bias. “They want to think that they are more malleable and more liberal than they actually are.” Or maybe, when the risk-averse Singaporean voter thinks about political change “every now and then”, what they actually mean is every few centuries.

Politics: Singapore ‘wants’ a two-state solution

K Shanmugam, home affairs minister, confirmed this week that Singapore would still not join the over 140 other countries to have recognised the state of Palestine. He said three conditions were needed for the state to be viable: a physical space, a population, and a functioning government. He believes that recognition now would likely harm them. (Nevermind that Palestinians themselves want international support.) Even without the ongoing genocide, our national position reeks of appeasement and moral cowardice. Halimah Yacob, former president, rebutted Shanmugam’s claim by explaining simply why recognition would help, not harm. History will remember the courageous.

Some further reading: In “Genocide in Gaza? Our moral responsibility”, Jom describes Singapore's problematic relationship with Israel.

Society: Who’ll pull the plug on you?

Human beings procrastinate. We put things off, especially tasks that feel overwhelming, uncertain, or tedious. We avoid what’s stressful or offers no immediate reward: from the mundane and quotidian; to weighty, life-defining decisions, like planning for old age and death. But with Singapore set to become a super-aged society next year, the government has started nudging us past our inertia on addressing a vital question: who’ll make life decisions for you when you’re no longer able to?

This week, the Ministry of Social and Family Development announced that more than 350,000 Singaporeans have made a lasting power of attorney (LPA) as of August 15th. Nearly 290,000 are aged 50 and above, surpassing the 2025 target of 240,000. The LPA push is part of a broader multi-agency, legacy-planning campaign launched in 2023, which also covers CPF nominations, advance care plans (ACP) and wills.

An LPA lets a person (the donor) appoint one or more trusted donee(s), aged at least 21, to make decisions on their behalf if they lose mental capacity. Donees may decide on personal welfare, property, and financial affairs, and even sign deeds. A separate, non-binding ACP helps convey an individual’s healthcare preferences. While an advance medical directive (AMD) is a legal document stating that no extraordinary life-sustaining treatment be given if one is terminally ill or unconscious. To encourage uptake, LPA Form 1 fees are waived until March 2026. Where accepted, CDC and SG60 vouchers can also be used to pay a certificate issuer—an accredited doctor, lawyer or psychiatrist—who serves as independent witness and co-signatory, ensuring that the donor understands the implications and is acting voluntarily. LPAs come in handy in critical situations. Donees can, for instance, appoint someone to care for a child with autism if the parents become incapacitated; make medical decisions for an elderly relative with dementia; consent to surgery or manage long-term care for a donor left in a coma. Without an LPA, loved ones can face a lengthy and costly deputyship application.

Yet, instruments that lay out end-of-life wishes raise thorny questions of autonomy, justice and identity. Should our competent selves dictate the choices of our vulnerable future selves? Can we really know now whether preserving dignity or alleviating suffering will matter more to us then? Families fracture: siblings quarrel, spouses grow estranged, LPAs get revoked. These directives may safeguard personhood when faculties fail, but they also entrust immense power to others, making legal clarity, moral responsibility, and care essential. A lasting power of attorney, while practical, deserves time and attention before signing. Otherwise, the chances of it lasting are diminished.

History weekly by Faris Joraimi

It’s a trivial coincidence that Singapore’s prime minister shares his name—in Anglicised form—with one of the most famous leaders of a city-state in history. But even minor coincidences can be too good to overlook; especially when the choice of names, and their fortunes, was no small matter for leaders across traditions of human government. Lorenzo de’ Medici ruled the Republic of Florence in the mid-15th century, as part of the Medici family of bankers. Their wealth financed the Renaissance, sponsoring famous landmarks and figures from Michelangelo to Leonardo da Vinci. Florence wasn’t yet part of “Italy”, which only became a unified entity in 1871. Perhaps like Singapore today, Florence was a small state amidst intense struggles between large powers—the Ottoman and Holy Roman empires, France, and the Papal States—which it depended on economically but kept out of internal affairs. A shrewd diplomat, Lorenzo stabilised his region through peaceful ties with Florence’s trading partners and neighbouring city-states. His reign is remembered as a golden age.

This early in his term, our Lawrence probably doesn’t have the luxury of contemplating his legacy in such grandiose terms. Singapore’s elites, however, often looked to historical European city-states as models, especially Venice. It was in our Social Studies syllabus for a decade, removed in 2016. Some comparisons are reasonable: both Singapore and Venice, without valuable natural resources, are marvels of civic engineering and maritime centres where spectacles display wealth and power to citizens and visitors. But I also recall our bedrock principles of meritocracy, good governance, and economic pragmatism strangely transplanted to the glittering Adriatic, as if the Venetians shared our political ideals. In reality, Venice (like Florence) was a stratified society ruled by noblemen, whose connections unlocked revolving doors between positions of influence. It was never a nation-state, and acquired a hinterland through conquest. Signs indicate we may be there, as shown by Michael Barr’s 2012 study on Singapore’s tightly-knit elite networks, and our reliance on overseas hinterlands of labour, sand, and markets. Lee Kuan Yew said Singapore would do well if it lasted half as long as the thousand years Venice did. We already follow its formula: egalitarian in name, never a nation in the strict sense, and a reliable service-centre for global wealth.

Singapore’s sterile political climate today sets it apart from the Renaissance city-states. Yet it was the latter’s dramatic power struggles that birthed the theory of politics so loved by Singapore’s establishment: a ruthless game of self-preservation, described by Machiavelli in a 1532 manual of statecraft dedicated to Lorenzo, “the Magnificent”. The ruler apparently never read it. Lawrence the Mellow may never have to, either; he has subtler methods these days, anyway.

Arts: Culture vouchers

Got your groceries and your postgraduate diploma? Good. With “bread and butter” settled, Singapore’s decided it’s now “CDC voucher” time for the arts. The SG Culture Pass was rolled out on Monday, where every Singaporean aged 18 and up received S$100 in digital credits to spend on arts and heritage programmes of their choice. The choice, admittedly, remains limited for now, but there are 400 performances, workshops and events lined up, with more to come. You can catch a Mandopop jukebox musical, take an incense workshop with an indie perfumery, or bring your kids to a nonverbal puppetry performance that gently introduces them to grief. The Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth is still weighing the use of these credits for local films and books, the artforms that have occupied the headlines over the past year, as their storehouses and stewards have struggled to stay afloat. Artists and arts groups were cautiously optimistic about the voucher rollout, though some feared that the public might squander their share on early adopters, and leave none for later programmes in the three-year spending period. Even our well-established upskilling credits run the risk of being overlooked, or forgotten; earlier this year, SkillsFuture Singapore said that about 70 percent of those who’d received a credit top-up expiring at the end of the year had yet to use it.

Culture vouchers aren’t unique to Singapore, but like many other processes, our state has opted for a top-down approach to quickening the local pulse when it comes to setting up a date with the arts. (The etiquette around letting your date pay for a date in vouchers, however, remains up for debate.) There are other social welfare models that might persuade our pragmatic public of the intrinsic value of the arts, rather than the instrumental path we’ve taken thus far. In Finland, for instance, employers can opt to offer their employees a sports and culture benefit (virikeseteli) of up to €400 (S$600) per individual per year; this nationwide benefit is tax-free for the employee, and tax-deductible for the employer. A ministry isn’t involved in approving what activities it deems fit for consumption—that’s up to the companies administering the benefit. Neither is the burden wholly on arts, sports or even wellness companies to apply to be part of this ecosystem. In a time of cultural grief and shuttering spaces, it bears reminding that a creative renaissance requires financial and emotional investment from all of us, whether that’s the state, the artist, the private or the public.

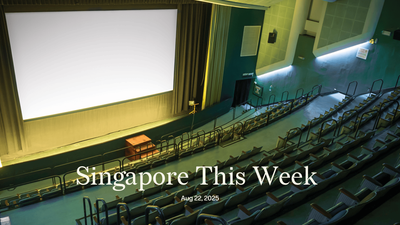

Arts: Band-aid on a bullet wound

School’s out. What do you pick: Shaw, Cathay or GV? These were the cinematic tribes of the elder millennial, depending on whether you were an audiophile, had a handsome allowance, or were game to settle for anything available and affordable. Singapore, it seems, has settled for the slow deaths of F&B and cultural spaces fumbling for footholds in a brutal rental market and an even crueller attention economy. Cathay Cineplexes is the latest, and perhaps largest, casualty in a string of closures. No amount of culture voucher transfusions could have resuscitated it. The operator finally folded several days ago after keeping creditors at bay for months—and outlasting beloved indie cinema The Projector by a matter of weeks. In February, the landlords of its Century Square and Causeway Point outlets demanded S$2.7m, followed by another S$3.4m demand for its Jem outlet in July. Six of its outlets had already shuttered over the past three years. But, even then, cinemagoers were caught by surprise. ST found several stragglers at the Downtown East outlet who’d bought their tickets just a day before, and another at the Century Square outlet who’d invested in S$100 worth of Cathay’s “Save our Screens” vouchers and had yet to use them up before the supposed December 31st expiration. Cathay was joined by F&B mainstay Prive Group, which announced the closure of all of its restaurants at almost the same time.

There were other smaller fatalities whose funerals may have gone unnoticed. One of them was Vertigo 26, one of the first post-pandemic vinyl bars to break into the scene. The basement-level bar, nestled under the MINT Museum of Toys, played everything from Asian disco to “deep jazz cuts”—so went a DJ’s ode to the now-defunct space. Then there’s Enclave Bar, another post-pandemic passion project along Neil Road, which has just announced that it’ll be closing in late October. The four-year-old small business had been committed to giving early-career musicians a fair shot. “Most times when people want to create events, they say they have limited resources in terms of finance,” its founder, musician Ritz Ang, told Catch. “I’m like, okay, you don’t have to pay for the space. Just do your thing. We’ll work something out.” Artists, for instance, might pocket ticket sales while the venue profits from bar sales. These bartering models are commonplace in neighbouring Malaysia and Indonesia, but they’ve been tougher in the Singaporean market, governed by a different set of hypercapitalist rules. Perhaps our generous indie spaces weren’t meant for a game of capitalist “Survivor”. Might all of them be replaced by interchangeable mala hotpot chains or mediocre coffee monopolies? It’s up to us, and our cultural diet, to ensure that our diverse and resilient polyculture doesn’t become a singular, plague-susceptible monoculture.

Faris Joraimi, Abhishek Mehrotra, Corrie Tan, Tsen-Waye Tay, and Sudhir Vadaketh wrote this week’s issue. Sakinah Safiee contributed.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.