History weekly by Faris Joraimi

Toiletries, umbrellas, plushie keychains: stamped with party insignia, these objects lend that carnival atmosphere to election season. With our annual ritual of receiving National Day Parade goodie bags and patriotic memorabilia, consumption is Singapore’s shared love-language. On the campaign trail, all that merchandise doesn’t just give supporters and would-be voters something material to latch onto, unlike ideas and promises; they’re also a great vehicle for publicity, worn and carried by the masses on streets, in public transport, and into their homes. At the time of writing, the Workers’ Party's “Hammer Bundle” and hammer plushie keychain are out-of-stock in the party’s online shop. The retail of party merchandise feels like a more recent strategy of fundraising and soliciting support in Singapore’s electoral landscape, but campaign posters and banners have been around since our earliest experiments with parliamentary democracy, when the 1955 Rendel Constitution allowed for the majority of legislators to be elected, rather than appointed by the British colonial government. Treasures at Home, a family-run antique shop in Tai Seng, has a big tin sign from the election period announcing that fateful year, when the Labour Front won.

In a Straits Times feature, Treasure at Home’s father-son duo Wak Sadri and Emyr Uzayr flaunted their collection of vintage People’s Action Party posters and Barisan Sosialis newsletters from the 1960s to 1980s, minimalist but impactful. There’s something about the clean, modernist designs of these materials that you don’t find in campaign trappings today, that captures an art history, but also a mood, a flavour, from a different time. And of course, they’re the work of many unnamed sign-painters, illustrators, engravers, and lithographers. Creative labour, then and now, produces the media that allows us to participate in the democratic process. (Think of all the reel smiths, memelords and videographers supplying content for our digital feeds.) Every detail in those vintage posters, from the candidates named to the voting districts now out of memory, record the vagaries of electoral politics. Their variety of scripts reflect our polyglot social world. Of all people, antique dealers are probably most attuned to the rapid tempo of change that churns out junk. “You should keep things,” Wak Sadri said. Who knows how significant this election will be? As a Pasir Ris resident, I think those Singapore Democratic Alliance posters, with their pithy captions, make great keepsakes.

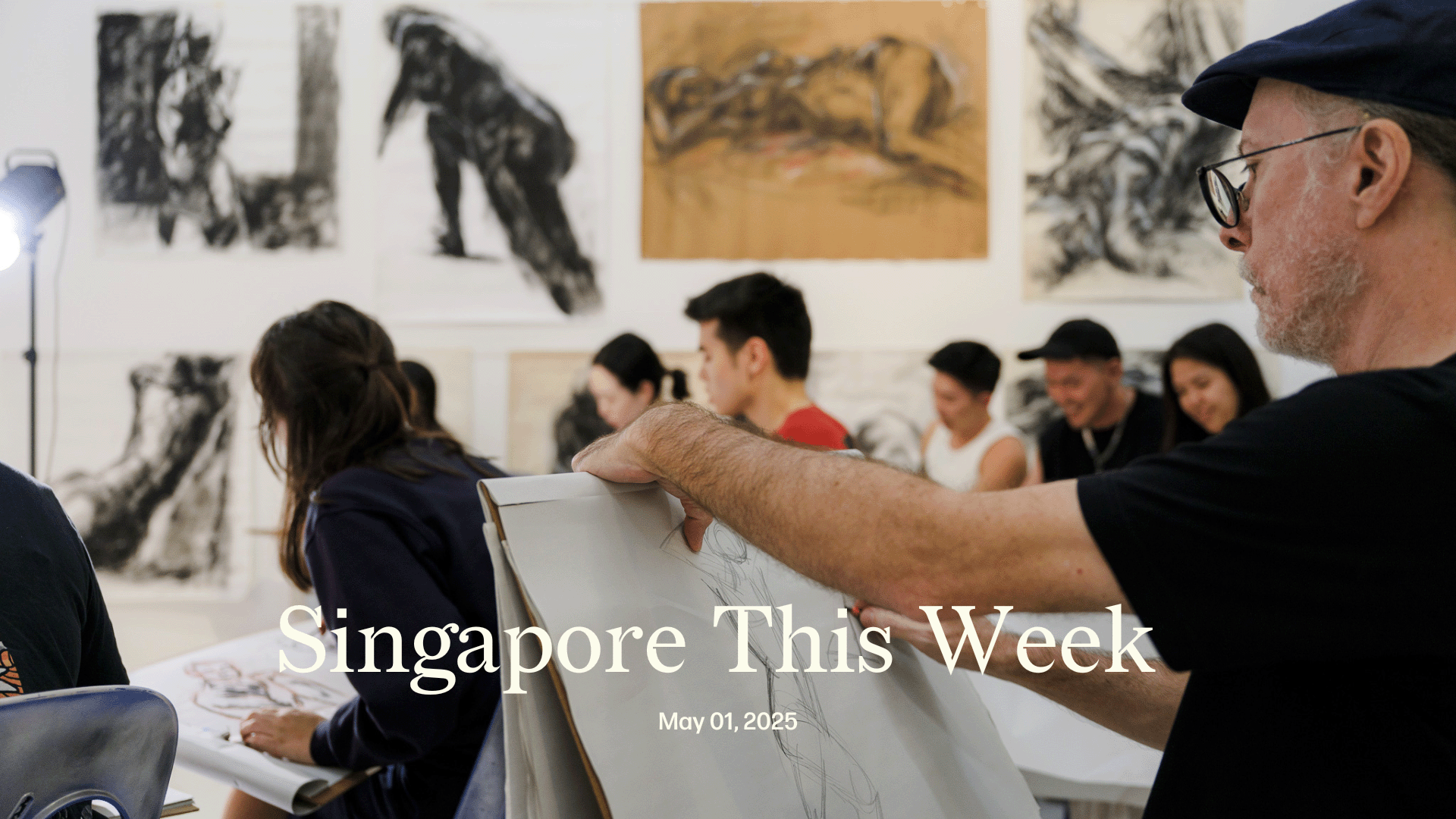

Arts: Striking a pose

There are dozens of nude bodies pinned up on the wall, but these aren’t your average pin-ups. Their faces are largely obscured, their torsos tilted away from our gaze, revealing backs of stretched skin and coiled muscle, rendered in brisk strokes of chalk and charcoal. Smudges of pastel become splashes of light on a shoulder, elbow and thigh. These large sheets of paper aren’t just carrying bodies; they’re scored by long ridges from having been rolled up for years, and some are curling at the edges. These bodies—draped in chairs, soft with sleep, slouching out of the frame—are caught mostly in moments of repose. “Points of Articulation: Repose” is also the title of this tender exhibition at Yeo Workshop, which pays tribute to the late Solamalay Namasivayam (“Nama” to his friends), the understated and underappreciated artist-educator who was a pioneer of the art of figure drawing in Singapore. The 33 large-format drawings, mostly made in the 1990s and 2000s, are a fraction of the prolific Nama’s body of work. His sketchbooks, stuffed with meticulous skeleton studies, peel back layers of skin in an attempt to distill the magic of bodily motion.

Figure drawing, also known as life drawing, has shed most of its stigma in contemporary Singapore. Nama, who in his time struggled to recruit willing models and to persuade wary institutions of his artistic intentions, may never have imagined his chosen form’s eventual popularity. Life drawing groups and classes are now the pickleball of portraiture, drawing both amateurs keen to practise their anatomical proportions alongside established artists keen on the kinetic flow of the human form. Groups such as the Saturday Life Drawing Club, SG Life Drawing Circle and Arterly Obsessed host regular sessions; the popular Riot Drag Show’s joined the movement with Dragged and Drawn, where participants get to do up-close portraits of their favourite drag queens. These groups have fans from all walks of life, including Yvonne Tham, chief executive of national performing arts centre the Esplanade. Her gorgeous, minimalist inks are often accompanied by meditative captions, like this one, stemming from her sketch of a more elderly model: “Whatever mental or emotional age you may be in, your body has been doing its thing for as long as you have lived: growing, moving, changing, dancing, working; with your body you have embraced another, perhaps birthed another; your body may have been cut up, sewn up, burnt, radiographed…If your body were a machine, it is a miracle that it should still be functioning after all this!...So care for your body far better than anything else you possess.”

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.